Should investors worry about China's currency?

China's surprise move to devalue its currency rattled financial markets.

The Dow Jones industrial average on Tuesday suffered its first "death cross" -- a downward cross of the 50-day moving average below the 200-day moving average, a sign of a medium-term trend breakdown -- since 2011. Crude oil fell to test a $42 a barrel handle for the first time since March. Gold and silver are perking up. And Treasury bonds are soaring as investors scatter towards safety.

The catalyst was a 1.9 percent reduction in the value of the yuan following weak trade and inflation data over the weekend. That amounts to the largest one-day drop since China ended its dual-currency system in January 1994, and it returns the yuan's value to where it was in April 2013.

The Dow lost 212 points on the day, or 1.2 percent, to finish at 17,402. The S&P 500 fell 20 points, or 1 percent, to 2,089, while the Nasdaq Composite index decreased 65 points to 5,037.

By the looks of things, the turbulence is just getting started as many other countries from Japan to Switzerland, and even the European Union, have been monitoring and managing their currency valuations in a bid for growth and economic stability. China's aggressive move will not only send shockwaves throughout the financial system, but potentially affect global geopolitics as well.

Chinese central bankers had good reason to push down its currency, with a raft of data pointing to a sharper economic slowdown than Beijing is comfortable with.

Exports fell below expectations, dropping 8.3 percent in July over last year versus the 1.5 percent decline forecasted. Producer price inflation slid to its lowest level since October 2009 down 5.4 percent year-over-year vs. the 5 percent drop expected and the 4.8 percent drop posted in June. Corporate profitability in China has been under pressure. And the Shanghai Composite, ahead of the move, had fallen nearly 30 percent from its June high.

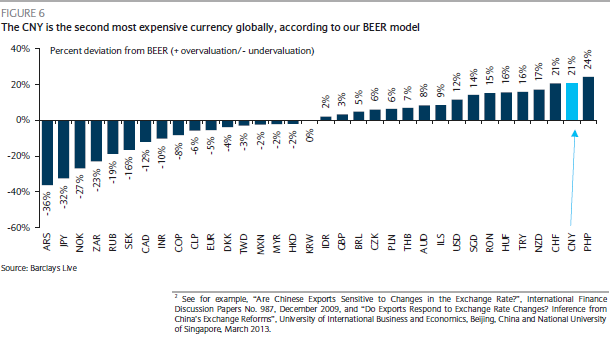

In their statement, the People's Bank of China (PBOC) explained that a strong currency was adding to the pressure on the country's exports. Since the yuan is loosely pegged to the dollar, the recent strength in the greenback has pushed the currency into overvalued territory, according to an analysis by Barclays.

While the move could help exports, the immediate effects, such as capital outflows, reactionary devaluations from trade partners, and possible credit market disruptions, are likely to happen first.

Moreover, while the move was labeled as a "one-time" move aimed at enabling the market to better value the yuan, it's an open question whether further devaluations will follow as Beijing tries to merge its on-shore and off-shore currency markets.

For the U.S., weakening China's currency risks further strengthening the dollar, which would weigh on exports. It could also push down overseas corporate profits. These potential near-term negatives have spooked U.S. investors and pushed stocks lower.

Indeed, Moody's Gerry Granovsky said today that the yuan devaluation "is credit negative for technology companies with significant operations in China, such as Apple, which already have to cope with a strong U.S. dollar." The move "further increases the cost of iPhones and iPads in the local market."

Apple (AAPL) shares fell 5.2 percent to close at $113.49.

PNC Financial Services Group economist Gus Faucher also notes that all of this could restrain already tepid inflation in the U.S., something the Federal Reserve has been patiently waiting to return to their 2 percent target. That, in turn, could push back the central bank's timing for raising interest rates, which many forecasters had predicted would come in September.

"The timing of Fed liftoff has always been a relatively close call in our view -- and with the devaluation of the Chinese yuan this morning, it just got a little closer," analysts with Bank of America Merrill Lynch said in a note. "A stronger U.S. dollar is both disinflationary and a drag on U.S. growth."

But Julian Evans-Pritchard at Capital Economics thinks investors may be overreacting, noting that the yuan adjustment is largely a technical change in the way China sets its currency value. Instead of setting the value, the PBoC will now base it off of the previous closing price and overnight shifts in the foreign exchange markets.

In his words, "Because the reference rate was previously set well above the market rate, the new approach meant the reference rate had to be lowered sharply."

Whether the market turbulence continues depends, in large part, on whether the PBoC moves to shore up its currency or allows the decline to precipitate.