March of Dimes rates U.S., cities, states on preterm births

Babies born before 37 weeks can have serious health problems, yet too often, women in the U.S. are still giving birth preterm, earning the nation only a "C" on the latest report card from the March of Dimes. Some individual states and cities, though, are receiving higher marks.

"It's the eighth year we've released this report and it showed that the U.S. overall received a grade of 'C,' falling short of the 8.1 percent [preterm] birth rate that is the goal which we're trying to reach. We have, overall, a 9.6 percent preterm birth rate," said Dr. Siobhan Dolan, an obstetrician-gynecologist at Montefiore Medical Center, in the Bronx, New York, and a medical adviser to the March of Dimes.

The good news, Dolan said, is that for the past several years, the preterm birth rate has dropped down a small amount. "It is moving in the right direction," she said.

Thirty-nine weeks of pregnancy is the target time for a healthy birth, she said. The U.S. preterm birth rate ranks among the worst compared to other "high-resource countries," the March of Dimes said in a statement. Babies who are born earlier are at risk for serious and lifelong health problems, including breathing problems, jaundice, vision loss, cerebral palsy and intellectual delays.

Worldwide, 15 million babies are born preterm, and nearly one million die due to early birth or its complications, according to the March of Dimes.

Dolan said this is the first time the organization's Premature Birth Report Card has graded U.S. cities and counties, and the findings show there are wide disparities state-to-state and city-to-city.

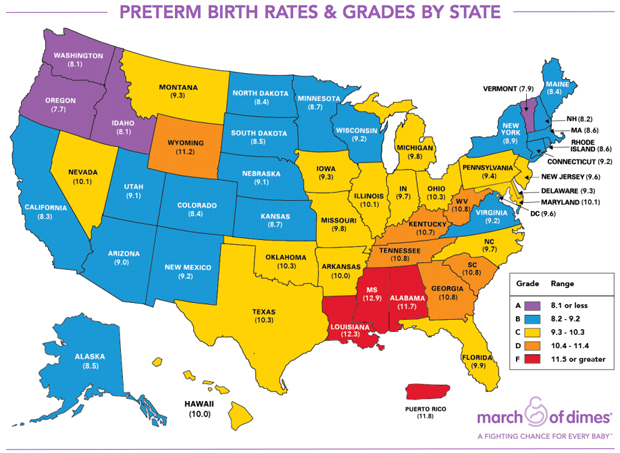

For states four boasted an "A" grade: Idaho, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington.

Nineteen states received a "B," and 18 states and the District of Columbia earned a "C." Six states were graded "D." Straggling behind with "Fs" were Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Puerto Rico.

When it came to top-notch grades for cities, Portland, Oregon received an "A" for having the lowest preterm birth rate -- 7.2 percent -- out of the top 100 cities with the most births nationwide. Lowest-scorer Shreveport, Louisiana, logged an "F" for an 18.8 percent preterm birth rate.

In addition to Portland, the cities of Oxnard, California; St. Paul, Minnesota; and Seattle, Washington, were the only other cities to achieve "A's."

Dolan said the report suggested that the variation in rates is due to racial, ethnic and geographic disparities within states. Maine showed the smallest gaps among racial and ethnic groups in its preterm birth rate, while the District of Columbia had the largest gaps.

"States like Louisiana have a lot of challenges. I don't have the exact answers, but some issues that can be targeted may be access to care, making sure women have health insurance and have care before they become pregnant," Dolan said.

Dr. Louis Muglia, co-director of the Perinatal Institute and director of the Center for Prevention of Preterm Birth at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, said, "The good news is the rates are coming down in the U.S., which I think is very encouraging. There have been fewer teen pregnancies and we are reducing preterm birth in women who've had previous preterm births."

But the "C" grade for the U.S. reflects bigger issues, he said. "I think a large part of this reflects not just the pregnancy outcome but the health of our community and the health of women not only during pregnancy but when they enter pregnancy. We have to look at this as a continuum," Muglia said.

Specific circumstances -- how impoverished a woman is, her social and environmental stress, everything a woman is exposed to -- have a "huge" effect on pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes, said Muglia.

"African-American moms in the U.S. have a 50 percent higher rate of preterm births as women of European ancestry -- Caucasian women," he said.

The March of Dimes said some states earned high marks due to the implementation of state and local programs and policies involving health departments, hospitals, and doctors. They offer a tool kit that can help hospitals improve their outcomes.

Muglia points to California's successful efforts at reducing preterm birth through better education of pregnant women and providing maternal support services.

Dolan said states could also improve preterm birth rates by educating healthy pregnant patients to aim for 39 weeks of pregnancy (instead of electing to induce birth earlier, for example).

"Some states need to get on board with eliminating elective early births," Dolan said. "There was this sense that 37 weeks was okay. It's hard at the end of pregnancy. You're uncomfortable. I might have been tempted at 38 weeks. But if you have nothing going on medically, then 39 weeks is best. Once women hear that, and health care systems embrace that, rates will go down."

The March of Dimes announced a new goal for the nation to lower the preterm birth rate to 8.1 percent of live births by 2020. "We'd love to see all 50 states receive an 'A,'" Dolan said.