March madness? NCAA fights full-court press on player pay

A few years ago, former UCLA basketball star Ed O'Bannon made a startling discovery: A college basketball video game included a player who very much appeared to be him. O'Bannon, who now works at a car dealership outside of Las Vegas, was not being paid for the use of his likeness. But he knew someone out there was.

"I felt betrayed," he says. "How would anyone feel if their likeness, at any level, is sold and they aren't compensated? They weren't even asked if their likeness could be sold?"

O'Bannon's anger led to an antitrust lawsuit that fundamentally threatens the business model of the National Collegiate Athletic Association, the governing body that rules over college athletics. Lawyers are now gearing up for a crucial June hearing that will decide whether the case will go forward as a class action; if the plaintiffs are successful, it could mean thousands of previously-unpaid college athletes laying claim to billions of dollars in revenue. The case has the potential to transform the college sports landscape in a way that will leave some fans lamenting the dismantling of a system they don't believe needs to be fixed.

At the heart of the suit is this question: Does the NCAA, which runs the "March Madness" college basketball tournament that kicks off next week, work with colleges and universities to exploit the young athletes that it purports to celebrate?

"To not compensate the players is not the way our economic system is structured," says David Berri, a sports economist at Southern Utah University. "These players are clearly being exploited. At the end of the day, you're saying you should have people work for you and not pay them."

The NCAA - which declined to directly answer questions for this article - does not see it that way. In an interview with PBS' "Frontline," NCAA president Mark Emmert said that "student-athletes" are given "remarkable opportunities to get an education at the finest universities on Earth" while developing their athletic skills.

"There are many, many students around the world who would love nothing more than to be able to come to an American university and gain access to American intercollegiate athletics, because it's such a great place to develop skill and to have that great experience," he said.

Critics say that's not nearly enough. In 2010, the NCAA announced that it had reached a 14-year, $10.8 billion deal with CBS Sports and Turner Broadcasting to broadcast "March Madness," which works out to more than $770 million per year. (CBS Corporation is the parent company of both CBS Sports and CBSNews.com.) The conferences also have their own lucrative TV deals: The Atlantic Coast Conference, for example, has a 15-year deal with ESPN worth $3.6 billion - more than $17 million per school per year. Schools, conferences and the NCAA also profit from gate receipts, sponsorship deals, apparel sales, video game and rebroadcast rights and other income sources.

The resulting revenue has flowed to Emmert, who makes an estimated $1.6 million per year, and other executives at the NCAA. It has driven a massive inflation in the salary of collegiate coaches, including the University of Kentucky basketball's John Calipari ($5.2 million per year) and University of Alabama football's Nick Saban ($5.62 million per year). It has also meant the construction of state-of-the-art training facilities at universities around the nation, which are used to convince top recruits to join the program.

But it has not gone directly to any of the players who are ultimately responsible for generating all that revenue, the vast majority of whom will never make it to the NFL or NBA. Under NCAA rules, players cannot be paid for their efforts or given gifts of any kind. They also cannot cut individual sponsorship deals - despite the fact that many are required to wear uniforms that are affixed with corporate logos.

"Any other American can capitalize on their status, on their fame, on their value, and receive it fully," said Ramogi Huma, a former UCLA football player who is president of the National College Players Association. "But college athletes are being carved out."

Fair Market Value

As Sports Illustrated's Seth Davis has pointed out, the players are paid in one sense: Most are provided scholarships that cover the cost of their education and a significant portion of their living expenses. There are no guarantees, however, those scholarships will last.

Most Division 1 men's basketball and football scholarships are offered on a one-year basis. If a player gets injured or does not perform at the level expected by his coach - or a new coach simply wants to work in a different system - he might not see that scholarship renewed for another year.

The NCAA has taken steps to address this: It recently lifted what had been a ban on multiyear scholarships, prompting some schools to begin offering them. The decision barely survived the objection of more than 200 schools, which wanted the flexibility that comes with cutting the scholarships of players they no longer felt they needed.

Four-year scholarships tend to go only to the strongest recruits, however, and they can be revoked if a coach decides a player violated a team rule. And players can lose their scholarship if they fall too far behind academically, which is not hard to do when they have to spend dozens of hours each week focused on athletics.

The NCAA developed a unique tool called the Graduation Success Rate that allows it to claim that athletes graduate at higher rates than non-athletes. But according to data from the Collegiate Sport Research Institute (CSRI) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the NCAA's figures are misleading.

The CSRI calculates that students who play men's basketball at Division 1 schools graduate at rates 20 percentage points lower than non-athletes who attend school full time - and the gaps are highest in the major conferences (30 percent). The "graduation gap" is bigger for black basketball players (26.7 percent) than whites (14.6 percent). The CRSI also found that Division 1 football players graduate at lower rates than full-time male college students. (A very small percentage of these athletes - less than 2 percent - do not graduate because they move to the NBA or NFL before finishing college.)

After U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan called for the NCAA to ban schools with graduation rates of less than 40 percent from participating in the "March Madness" tournament, the NCAA mandated that teams that fail to meet a 50 percent graduation rate for three straight years be banned from postseason play and face other restrictions.

"They don't give a moral damn about the athlete," argues former sports marketing executive Sonny Vaccaro. "Because they can't say it's about education. It's irrefutable that it's not."

Berri says that any focus on scholarships misses the point. He uses the example of former University of Kentucky basketball player Anthony Davis, who Berri estimates generated more than $2 million in revenue last year - in exchange for a scholarship worth perhaps $30,000.

Players, Berri argues, should be paid what they're worth in a competitive marketplace. Their compensation could include a scholarship, he says, but it wouldn't necessarily have to. His point is simply that the players should get "as much or as little as the market allows."

"I would expect that for most universities, like Southern Utah University, we would probably still just give them a scholarship," said Berri. "That's about all they're worth. But for a school like Kentucky, where they're generating a lot more revenue for them, they should be free to pay them as much as the market allows them to pay them."

In college athletics, the only time most people hear about players being paid is when the NCAA is investigating them for taking money illicitly.

"In a market economy, you should be allowed to ask your employer for money," said Berri. "And nobody should think that's a scandal."

Under the current system, players at big name schools often struggle simply to make ends meet. Huma recalls wondering as an undergraduate, "How is it we can generate all this money, yet we can struggle for basic necessities, including food?" Huma's organization is seeking a $3,000-$5,000 increase in athletic scholarships, which are capped by the NCAA; the NCAA is currently considering a $2,000 increase. In a 2011 study, the National College Players Association and Drexel University Department of Sport Management found that the average Duke University basketball player had a fair market value of $1,025,656. That average player, the study found, was living just $732 above the poverty line.

Drexel professor Ellen Staurowsky, a co-author of the study, said she believes players should be treated as employees, not students.

"The healthiest thing that could happen for the big-time football and men's basketball programs is to be designated as a college sport pro league and the athletes would be paid, with the opportunity to pursue their degrees in the form of tuition remission programs without the requirements of a full time student," she said.

Andrew Zimbalist, a sports economist at Smith College, disagrees. He argues that establishing a market for 17-year-old recruits would both "create chaos" and "violate college culture." Zimbalist does believe, however, that "we should be knocking the money off the coaches' salary and paying full cost of [students' education]."

The NCAA maintains that it does not pay players because they are "students who participate in athletics as part of their educational experience," as then-NCAA president Myles Brand said in "State of the Association" remarks in 2006. That idea, he said, is at "the heart of the enterprise."

The NCAA's first executive director, Walter Byers, put it in far different terms. The reclusive Byers, who became a harsh critic of the NCAA late in life, testified that he conceived the phrase "student-athlete" to ensure that athletes would not be considered employees. As such, an athlete that is injured during a game or practice is not covered under workers' compensation, and his school is not required to cover the costs of his medical care.

"There are some serious gaps in protections. If you see a player go down in a game in the 'March Madness' tournament each year, no one knows that that player is going to have his medical expenses taken care of," said Huma.

Byers wrote in his memoir, "Unsportsmanlike Conduct: Exploiting College Athletes," that the NCAA operates under a "plantation mentality resurrected and blessed by today's campus executives."

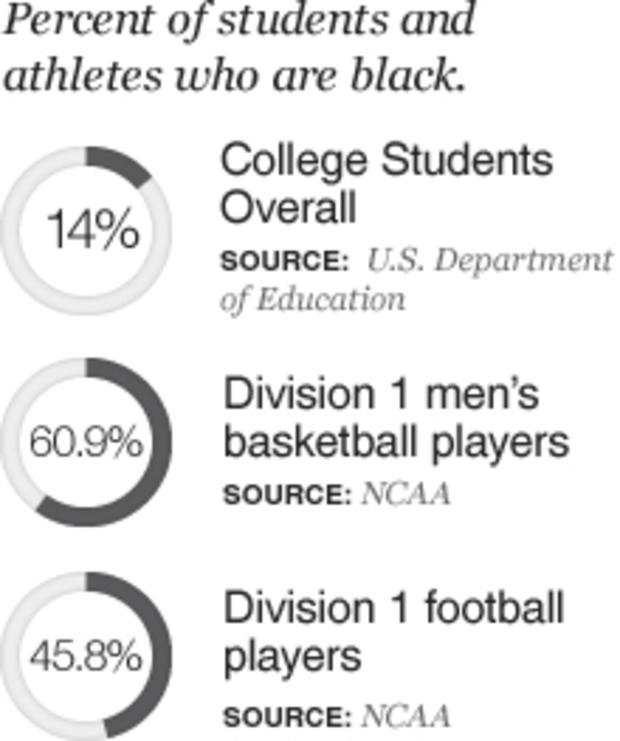

"There's a race and class component to this," said Staurowsky. "When we have the percent of players in both revenue-producing football and basketball teams that are predominantly or largely African-American, and we know that in terms of graduation rates that African-American athletes are the most at risk and the most vulnerable not to graduate, and from a financial point of view sometimes coming out of family circumstances that are challenging, I think to not realize that there is a racial and class component to this is really problematic. And I think that's part of the reason why we really have to embrace this moment and really think very carefully about how to move forward."

The O'Bannon Case

The O'Bannon case, which has attracted NBA Hall of Famers Oscar Robertson and Bill Russell, is grounded in the notion that "the NCAA imposes restrictions on college athletes which unduly interfere with the market for their compensation and the value of their interests in licensing and broadcasting," according to interim co-legal counsel Michael Hausfeld.

The case began when former college athletes, including O'Bannon, objected to the NCAA and others profiting off their likeness after they graduated. The plaintiffs are also seeking damages for revenue generated when these athletes were still students, which is what pushes the stakes into the billions of dollars. Roger Noll, an economics professor emeritus at Stanford and an expert for the plaintiffs, calculated that for the 2009-2010 season, basketball and football players in the Pac 10 - just one conference, for one year - would be owed a combined $56.6 million for the broadcast rights alone.

The NCAA, which lays out its legal position here, has strongly objected to efforts to classify the case as a class action. In January, a federal judge ruled that the case can move forward over NCAA objections; the hearing on class class certification is scheduled for June. The plaintiffs are arguing, essentially, that O'Bannon's situation is similar to other college athletes; the NCAA maintains that his situation is unique, and thus a class action is unfounded. The case is scheduled for trial next year.

(UPDATE: The NCAA filed a brief on Thursday objecting to class certification. "The NCAA is not exploiting current or former student-athletes but instead provides enormous benefit to them and to the public," said Donald Remy, NCAA Executive Vice President and Chief Legal Officer, in conjunction with the filing. "This case has always been wrong -- wrong on the facts and wrong on the law. We look forward to its eventual resolution in the courts.")

It is not clear how the money would be distributed if the plaintiffs are successful. Hausfeld suggested that all players - both stars and bench players - might get an equal portion of television revenues from the "March Madness" tournament, and that the money would be held in a trust until their collegiate careers are over.

The case centers on the collective agreement between NCAA members not to bargain with athletes over compensation in exchange for signing over their rights. Under the current system, athletes seeking to participate in NCAA athletics must fill out a form which in the 2010-2011 academic year included the clause: "You authorize the NCAA ... to use your name and picture in accordance with Bylaw 12.5, including to promote NCAA championships or other NCAA events, activities or programs."

Hausfeld said players are expected to sign the document as a formality, without a lawyer present; the document says the players should read the NCAA's extensive rulebook before signing, a step few seem to take. The plaintiffs maintain that athletes have no choice but to accept take-it-or-leave-it terms to participate in college athletics, and thus get less than they would in a competitive market for their skills.

"This document that students sign gives the NCAA the right to use their image to promote NCAA events," said Zimbalist. "And it also stipulates there won't be any commercial exploitation of those images. So I think they have the NCAA over the barrel on that one."

In addition to seeking damages, the plaintiffs are asking the court to prevent the NCAA from keeping athletes from signing endorsement deals or otherwise profiting from their image. That would mean a player like Texas A&M quarterback Johnny Manziel could sign a lucrative deal with Nike and appear alongside Michael Phelps in ads for Subway sandwiches, despite still being in college.

O'Bannon was a college star who likely could have cut an endorsement deal himself; he was pictured on the cover of Sports Illustrated in 1995 celebrating UCLA's NCAA title. After being drafted in the first round by the New Jersey Nets, O'Bannon spent two remarkable seasons in the NBA before playing overseas; he now keeps his framed UCLA jersey behind his desk at the car dealership where he works to support his family.

"A lot of the athletes that are in college are being exploited," said O'Bannon. "A lot of people are getting rich off of their blood, sweat and tears."

Is the NCAA in trouble?

Vaccaro believes that the O'Bannon case and discussion around paying players could mean the organization losing control of college basketball. "It has survived in the past, but today - they're at the center of the storm right now," he said. "All their pimples are showing."

In 1984, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the University of Georgia and the University of Oklahoma in an antitrust suit that struck down the NCAA's football contracts with television. That freed the college football powers to circumvent the NCAA and keep the revenue from bowl games and other events for themselves.

The NCAA now makes more than 80 percent of its revenue -- $871.6 million - from the "March Madness" tournament. Once the NCAA's contract with CBS Sports and Turner Broadcasting runs out, Vaccaro says, college basketball could "cut out the middle man." Vaccaro suggested the breakup of the Big East conference - which undercuts the NCAA's argument that it exists in part to maintain the revered traditions of old college rivalries - could be the first step in that direction.

But it's important to remember that the NCAA is essentially a tool of the schools - an umbrella organization that exists in part to enforce their agreement that the players not be paid. Phasing out the NCAA would make it more difficult for schools to enforce such limitations, which gives the schools an incentive to keep it around. Either way, the schools will still look out for their self interests - and that means, in most cases, trying to keep as much revenue as possible. (For evidence, look no further than the widespread opposition to the NCAA lifting the ban on multi-year scholarships.) In addition, it's difficult to see how a "March Madness" tournament could be organized without some sort of central governing body.

If the O'Bannon case or public pressure forces the NCAA and the schools to allow players to be paid, there are no shortage of issues to be addressed. One is whether Title XI of the Educational Amendments Act of 1972 - better known as "Title Nine" - means that any money paid to men's basketball and football players flow in equal measure into women's sports programs.

If the players were classified as paid employees, not students, this probably wouldn't be an issue. But would it be acceptable to fans to see their school represented by paid employees instead of traditional members of the student body? Would a shift to paid employee status undermine the connection that makes college sports so lucrative in the first place?

"I can't imagine this has any effect on the fans," said Berri. "They argued this back in the '70s - 'If you start having free agents in baseball, and they start switching teams, the fans will be turned off.' Baseball's more popular now than it was 30, 40 years ago. They have much bigger ratings, they have more fans - like 70 million fans show up every year. Same thing in the NBA, same thing in the NFL. You don't care if your players are paid, you care if they win. If you win, I like you. If you lose, I hate you. I don't care whether you were paid or not, that's not relevant to me."

Paying players would mean significantly lower salaries for athletic directors and head coaches - in many cases, the highest paid employee at a college or university - and less investment in facilities, since there would not be so much excess revenue flowing through the system. That's fine with many former college athletes, who bristle at the fact that players in the "March Madness" tournament can't afford to fly their parents out to watch the games while the coaches grow rich off college basketball profits.

O'Bannon, who described the NCAA as "crooked," said recruits with NBA and NFL dreams have little sense of the reality of college sports when they sign up.

"The kids that are coming out of high school and going to their respective universities are naive," he said. "Really, most of them have no idea. It's truly amazing the amount of money that is being made by these kids for the university as well as the NCAA. And the funny thing is - I don't really think it's all that funny I guess - the players themselves don't really understand. Don't know the money that is being made. And it's kinda sad."