"Man on the Moon": The 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 landing

One of the greatest achievements in the history of mankind began on July 16, 1969 – exactly 50 years ago today -- inside Houston's Johnson Space Center. Inside Mission Control on that summer morning, teams of NASA flight controllers sat nervously at their consoles. Together, they would guide three astronauts — Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins -- a thousand miles away on the Florida coast, as they climbed on top the world's most powerful rocket and blasted off on their way to the moon.

Across the country and around the globe, millions followed on TV, many of them glued to the gripping minute-by-minute account of the legendary CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite.

In a special hosted by "CBS Evening News" anchor Norah O'Donnell on the 50th anniversary, CBS News relives those dramatic moments as they unfolded, through the eyes of Cronkite and Neil Armstrong himself.

The "First Man" rarely gave interviews, but he spoke with CBS News several years ago and spoke powerfully -- and personally -- about his extraordinary feat. Hear from the man who made history – and the man who reported it.

How did we get here?

"Good morning. It's three hours and 32 minutes until man begins the greatest adventure in his history," "CBS Evening News" anchor Walter Cronkite told Americans at 6 a.m. on the morning of the Apollo 11 launch. "Three astronauts awakened at 4:15 this morning, an hour and 45 minutes ago. … Had a good breakfast and were pronounced fit as a fiddle and ready to go."

Eight years earlier, in an urgent address to Congress, President John F. Kennedy said, "I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal before this decade is out of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth."

The speech came at a time when America and the Soviet Union were locked in a battle for dominance -- each trying to prove its superiority by conquering space.

But in truth, the U.S. had just suffered a major setback.

"Yuri Gagarin's … flight in orbit around the earth only seemed to place us even further behind," said Cronkite.

"That the Russians would land a man on the moon before us seemed inevitable," Cronkite reported.

NASA poured a staggering $25 billion -- the equivalent of $263 billion today -- into the program, providing 400,000 jobs for men and women, determined to win at any cost.

In a rare interview, astronaut Neil Armstrong talked to 60 Minutes correspondent Ed Bradley in 2005.

"It was a remarkable time and a remarkable progress. Took a lotta people working very hard," Armstrong said. "Everybody loved the work and loved the challenge."

Nobody loved a challenge more than the boy from Wapakoneta, Ohio. Armstrong got his pilot's license at 16. By 21, he was flying combat missions over Korea -- 78 of them. "In Korea, I only bailed out once, fortunately," he said.

From there, he went on to another risky job test piloting the famous X-15, flying 4,000 miles-per-hour to the edge of the atmosphere. "Every flight in the X-15 was – it was an experience," said Armstrong.

But the spaceman also stayed grounded. In 1956 he married a woman he'd met at Purdue University, Janet Shearon. They started a family. But, tragically, they lost their second child, daughter Karen, to brain cancer when she was only 2 years old. Four decades later, he was still emotional about it.

"I thought the best thing for me to do in that situation was to continue with my work, keep things as normal as I could. And -- try as -- hard as I could not to -- not to have it affect -- my ability to do useful things," Armstrong told Bradley, his voice breaking.

Shortly after Karen's death, Armstrong joined a group of elite astronauts at NASA.

NASA PROMOTIONAL VIDEO: He was selected by NASA in September 1962 as one of the nine men making up the second group of astronauts. The long months of specialized training for space missions began in classrooms, observatories, field trips …

The program made great strides in record time. Then came that terrible day in November 1963 – the assassination of President Kennedy. The man who had dreamed of landing on the moon and worked so hard to make it happen would not live to see it.

"From Dallas, Texas, the flash apparently official. President Kennedy died at 1 p.m. Central Standard Time, two o'clock Eastern Standard Time. Some 38 minutes ago," Cronkite told the country.

Just three years later, another devastating blow when the Apollo 1 pre-launch test ended in disaster.

"America's first three Apollo astronauts were trapped and killed by a flash fire that swept their moon ship early tonight during a launch pad test … in Florida," CBS News' Mike Wallace announced in a special report.

Walter Cronkite rushed to the New York studio. He had known all three men: Gus Grissom, Roger Chaffee and Ed White.

"This is a time for great sadness, national sadness and certainly personal sadness -- the people in the space program, but it's also a time for courage and if that sounds trite I'll change the words to guts," Cronkite told Wallace.

Now, more determined than ever, the men and women of NASA plowed forward. But danger was never far away. In 1968, Armstrong was forced to eject while flying a lunar landing training vehicle. He was barely 200 feet from the ground.

"And if you didn't get out, that would have been your life?" Bradley asked Armstrong.

"Uh, yeah, probably would have," he replied.

"Yet somebody told me that after that happened … you went back to your office and sat down to do paperwork."

"It's -- that's true. I did. There was -- there was work to be done," Armstrong said laughing.

That cool head under fire didn't go unnoticed. In January 1969, Neil Armstrong was publicly named as commander of the three-man spaceship bound for the moon: Apollo 11. The famously modest Armstrong insisted he was no more special than any of the other astronauts. Just lucky.

"… A 38-year-old American named Neil Armstrong to be the first man to set foot on the moon," Cronkite reported. "He's a man of strong personality, a civilian test pilot of whom his wife says, 'Silence is a Neil Armstrong answer. The word no is an argument.'"

Armstrong would make the 240,000-mile journey with two other men. Edwin Aldrin was known to his friends as "Buzz."

"A West Pointer from the Class of 51. Graduated third in his class. Said to be the best scientific mind in the astronaut program," said Cronkite.

And Michael Collins. "Michael Collins … will be the command module pilot," Cronkite explained. "He, it must be … who will affect any rescue that can be made of those men after they get back off the surface of the moon."

The three men spent the next six months in rigorous training, determined to get it right. NASA wasn't taking any chances, either.

DAVID SCHOUMACHER | CBS NEWS REPORT: For today's news conference the astronauts were inside a special cage built at a cost of $6,000 to protect them from reporters germs.

"You're destined to become a historical personage of some consequence and I'm wondering if in that light you have decided upon something suitably historical and memorable to say when you perform this symbolic act of stepping down on the moon for the first time?" a reporter asked.

"No, I haven't," Armstrong replied as the crowd laughed.

DAVID SCHOUMACHER | CBS NEWS REPORT: The astronauts then put on their masks and went home where the germs presumably are friendlier.

But away from the cameras, the mask came off and Neil Armstrong the astronaut became Neil Armstrong the father, a dad tasked with telling his two young sons – 12-year-old Rick and 6-year-old Mark -- that the mission came with a risk.

It was a possibility few spoke about, but most thought about. CBS News had already produced three obituaries and President Richard Nixon would prepare a condolence speech just in case.

But there was no time to dwell on that.

"Do you harbor any fear?" Cronkite asked the astronauts two days before the launch. "How would you describe your attitude just before flight?"

"I wouldn't say, Walter, that fear is an unknown emotion to us," Armstrong replied. "I would say that, as a crew, among the three of us, really have no fear of launching out on this expedition."

Crowds packed the stands at the place once known as Cape Canaveral -- a name changed to Cape Kennedy in honor of the fallen president.

"We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard," President Kennedy said during a September 1962 speech at Rice University.

"Here it looks as if they're about to come out," Cronkite reported live from Cape Kennedy on July 16, 1969.

MISSION CONTROL: T-minus 3 hours, 4 minutes, 32 seconds and counting.

"It's going to be a journey certainly for the history books," Cronkite continued. "Of all of those things that have entered the history books in our generation, this will live the longest."

From launch to landing

LAUNCH CONTROL | MONDAY, JULY 16, 1969, 7:51 AM: This is Apollo Saturn launch control. T-minus 2 hours, 40 minutes, 40 seconds and counting. At this time the prime crew for Apollo 11 has boarded the high-speed elevator which will carry them to the 320-foot level … the spacecraft level.

"Good morning. It's T-1 hour, 29 minutes and 53 seconds and counting. If all goes well, Apollo 11 astronauts are to lift off from Pad 39A out there, on the voyage man always has dreamed about. Next stop for them -- the moon," "CBS Evening News" anchor Walter Cronkite reported live from from Cape Kennedy.

With an estimated one million spectators watching at Cape Kennedy and millions more around the world following along on TV and radio, the Apollo 11 astronauts finished their final work on Earth before setting off for the moon.

LAUNCH CONTROL: At this time, we're just in the process of closing the hatch on the Apollo 11 spacecraft.

"Buzz Aldrin said that when he got up to take a look around, that he took a moment to enjoy the view," 60 Minutes correspondent Ed Bradley asked Neil Armstrong during a visit to the launch tower in 2005.

"Well you can see here, this view is a magnificent view," Armstrong replied.

"Do you remember your thoughts back then?"

"I think I was -- probably not admiring the view. I was thinking about what was coming up and getting ready to go," said Armstrong.

LAUNCH CONTROL: T-minus 60 seconds and counting. Neil Armstrong has just reported back it's been a real smooth countdown.

"Did you have butterflies?" Bradley wondered.

"Sure," Armstrong laughed.

And with good reason. The explosive potential of the rocket Armstrong was sitting on was the equivalent of a small atomic bomb.

"When you got that much … explosive materials underneath you, a certain apprehension is merited," said Armstrong.

LAUNCH CONTROL: Twenty seconds and counting. … 10, 9 … ignition sequence start. 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, zero. All engine running. Liftoff, we have a liftoff. 32 minutes past the hour. Liftoff on Apollo 11."

"… building's shaking … we're getting that buffeting we've become used to," Cronkite said during liftoff. "What a moment, man on the way to the moon."

"What was the ride like?" Bradley asked.

"It was very jerky … a lot of rattle and shake like … riding an old train on a bad railroad track," Armstrong explained with a laugh. "Once we got into the second stage … the shaking completely disappeared, it was perfectly smooth and perfectly silent."

MISSION CONTROL: 11, Houston. Thrust is go. All engines you're looking good.

NEIL ARMSTRONG: Roger. Read you loud and clear Houston.

Apollo 11 was now moving away from Earth at thousands of miles an hour.

NEIL ARMSTRONG: You're seeing Earth as we see it out our left-hand window.

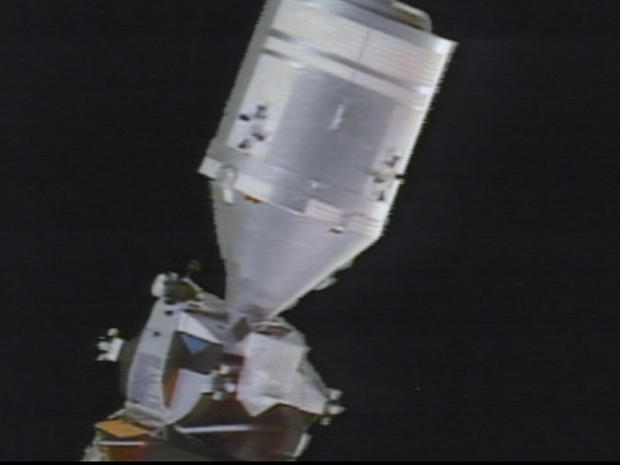

The crew settled into their home away from home. as shown in a 1969 CBS animation of the command module "Columbia" above the lunar module "Eagle."

Finally, after three days and a quarter million miles -- the moon.

Now, John Kennedy's challenge would be put to the test as Apollo 11's crew, along with thousands of support personnel back on Earth, prepared for landing.

"Just a little over an hour-and-a-half from now, the lunar module separates from the command module and the moon landing exercise begins," Cronkite explained during CBS News' coverage.

"So that's an exact replica of what you were in?" Bradley asked Armstrong during a visit to the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

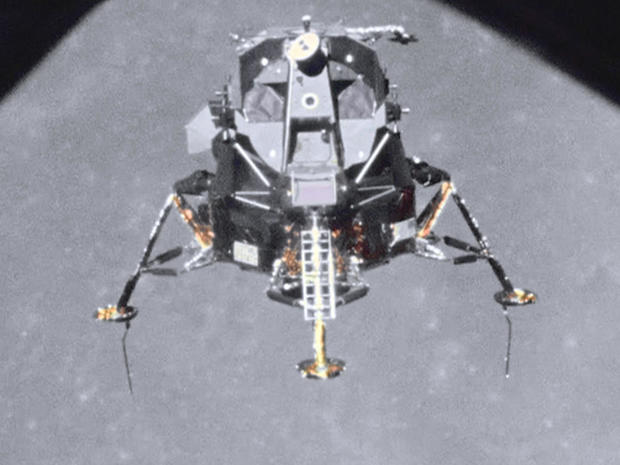

"Looks pretty much the same, yeah," Armstrong replied of the lunar module. "You know, there's an old saying in aviation that 'if it looks good it flies good.' And this has to be the exception to the rule. Because it flew very well. But it is the -- probably the ugliest flying machine that was ever been designed."

Many of the remarkable images, and many others seen in this 2019 broadcast, were captured by NASA cameras but not recovered and released until after Apollo 11's return to Earth.

NEIL ARMSTRONG: Eagle's undocked.

MISSION CONTROL: Roger. How does it look.

NEIL ARMSTRONG: The Eagle has wings.

MISSION CONTROL: Roger. Lookin' good.

While Armstrong and Aldrin pilot the lunar module to the surface, Michael Collins will stay behind in the command module to keep watch from above.

"The descent to the surface is a very complex -- operation. There were a lot of unknowns in that. So, I considered that most challenging part -- most worrisome part of the entire flight," Armstrong told Bradley.

MISSION CONTROL: We're go for landing.

As millions watching live around the world held their breath, everything appeared to be A-OK.

But in reality, the lander's computer was overloaded, and they were off-target.

"Our autopilot was taking us into … a very large crater covered with very large rocks about the size of automobiles. That was not the kind of place I wanted to try to make the first landing," Armstrong explained.

Bradley asked, "So, what did you do?"

"So, we took over manually and flew the craft out further to the west," Armstrong explained, "where the terrain, the lunar surface was much smoother."

MISSION CONTROL: Sixty seconds.

BUZZ ALDRIN That's 20 feet down, 2 1/2. Picking up some dust.

"So, you're looking for a better landing spot," Bradley noted.

"Exactly."

"You don't have a lot of fuel to do that," he continued.

"No, we were-- we were running a bit low on fuel," said Armstrong.

In fact, they were running on fumes with just seconds left to put the Eagle on the moon.

MISSION CONTROL: Thirty seconds.

BUZZ ALDRIN: Contact light. … Engine arm off.

BUZZ ALDRIN: 413 is in.

"We're home," said Wally Schirra, one of NASA's original Mercury Seven astronauts, broadcasting alongside Cronkite.

"Man on the Moon," said Cronkite. "Aw, gee."

NEIL ARMSTRONG: Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.

MISSION CONTROL: Roger, Tranquility. We copy you on the ground. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We're breathing again. Thanks a lot.

"Oh, boy. … Whew, boy," said an awestruck Cronkite, taking off his glasses and rubbing his hands together.

Man on the moon -- a singular moment in history. Years later, it still left one legendary wordsmith speechless.

"You are a man who I've known for years never to be at a loss for words, but you were at a loss for words then, I think," Bradley commented to Cronkite in 2005.

Laughing, Cronkite replied, "That's exactly the case. Exactly the -- Wally Schirra who was technical advisor for our broadcast kept asking me all morning, 'What are you gonna say? What are you gonna say when they land?' And I said, 'I don't prepare script for a thing like that. I -- I've -- I've gotta react-- as it comes to us.' Well, then it turned out I didn't have anything to say at all except, 'Wow, oh, boy. Oh, boy.' [laughs] Perfectly speechless."

One giant leap

CBS NEWS ANNOUNCER: This is CBS News color coverage of Man on the Moon, the epic journey of Apollo 11. This evening, a walk on the moon. Now here again is Walter Cronkite.

"How easy these words are rolling off our lips now: 'man on the moon, a walk on the moon.' And yet to say the words and to stop just a moment to think about them still sends a shiver up and down the old spine," Walter Cronkite said during the broadcast.

MISSION CONTROL: Uh, Neil this is Houston over.

NEIL ARMSTRONG: Go ahead Houston.

MISSION CONTROL: Uh, do you think you can open the hatch at this pressure?

NEIL ARMSTRONG: Uh, we're going to try it.

NEIL ARMSTRONG: OK, Houston, I'm on the porch.

MISSION CONTROL: Roger, Neil.

As the hatch swung open, Apollo 11's lunar module cast a shadow on the dust of the moon's surface.

MISSION CONTROL: OK Neil, we can see you coming down the ladder now.

By now, more than half a billion people were watching as the ghostly images beamed to Earth from a camera mounted on the lunar module.

NEIL ARMSTRONG: OK. I just checked … getting back up to that first step …

MISSION CONTROL: Roger. We copy.

NEIL ARMSTRONG: … It takes a pretty good little jump.

What viewers didn't see then was the angle filmed through the window by Buzz Aldrin.

More than 109 hours after liftoff, Commander Neil Armstrong stepped into history.

"There's that foot coming down," Schirra said.

"There he is," said Cronkite. "There's a foot coming down the steps."

NEIL ARMSTRONG: I'm at the foot of the ladder.

NEIL ARMSTRONG: I'm gonna step off the LM now.

"Boy, look at those pictures. Wow. Armstrong is on the moon, Neil Armstrong," Cronkite announced. "38-year-old American standing on the surface of the moon on this July 20th, 1969."

As Armstrong's left boot touched down, he delivered those famous words:

NEIL ARMSTRONG: That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.

"Do you recall how you came up with that -- 'A small step for man?' What was the inspiration for it?" Ed Bradley asked Armstrong.

"So, I thought, 'Well, when I step off, I -- just gonna be a little step.' They -- we-- step from there down to there. But then I thought about all those 400,000 people that had given me the opportunity to make that step and thought, 'it's gonna be a big something for all those folks,'" he replied.

The astronauts also captured photographs to bring the moon into full color.

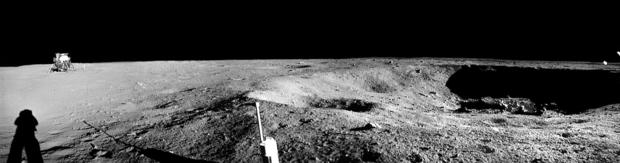

"It's a brilliant surface in -- in that sunlight," Armstrong told Bradley. "The horizon seems quite close to you, because the curvature is so much more pronounced than it -- here on Earth. It's an interesting place to be. I recommend it [laughs].

Nineteen minutes after Armstrong left the lunar module, Buzz Aldrin was ready to take his place in the history books -- with one quick check for safety:

BUZZ ALDRIN: Now I want to back up and partially close the hatch. … Making sure not to lock it on my way out.

NEIL ARMSTRONG [laughs]: Particularly good thought.

BUZZ ALDRIN: That's our home for the next couple of hours and we want to take good care of it.

BUZZ ALDRIN: … both hands down to about the fourth rung up.

NEIL ARMSTRONG: There you go.

"Welcome home," astronaut Wally Schirra said sitting beside Cronkite as Aldrin took his first step.

"And now we have two Americans on the moon," Cronkite announced.

NEIL ARMSTRONG: There you got it.

BUZZ ALDRIN: That's a good step,

NEIL ARMSTRONG: Yep, about a 3-footer.

"Three-foot first step with one-sixth gravity and look at that," Cronkite exclaimed.

BUZZ ALDRIN: Beautiful view

NEIL ARMSTRONG: Isn't that something?

NEIL ARMSTRONG: Magnificent sight out here.

BUZZ ALDRIN: Magnificent desolation.

Standing at the base called "Tranquility," Neil Armstrong read from a plaque on the lunar module's landing gear. It was a message about the mission for those watching, and those who might journey there in the future:

NEIL ARMSTRONG: "Here men from the planet Earth first stepped foot upon the moon July 1969 AD. We came in peace for all mankind."

Peace for all mankind -- at a time when the country was deeply divided, and more than 45,000 Americans had died in a war still raging in Vietnam.

"Today was no national holiday here," CBS News' John Laurence reported from Vietnam. "Tired, dirty American GIs came back from ambush patrols to learn that two of their countrymen had landed on the moon."

"What were you doing when two men landed on the moon?" the reporter asked a soldier.

"Well, I was out of an ambush last night, sir," he replied.

"I guess you were a little too busy to follow the progress of the astronauts."

"Quite busy, sir.

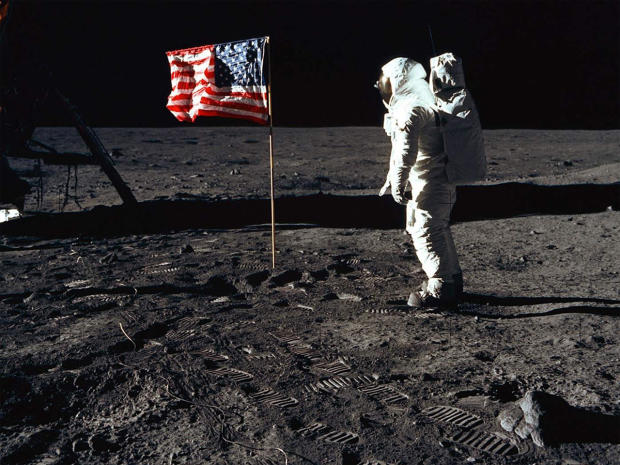

A world away, the American flag was planted into the lunar crust.

MICHAEL COLLINS: Is the lighting halfway decent?

BRUCE MCCANDLESS | NASA: Yes indeed. They've got the flag up now and you can see the stars and stripes.

MICHAEL COLLINS: Beautiful, just beautiful.

It became the backdrop for the longest distance phone call in human history.

BRUCE MCCANDLESS | NASA: Neil and Buzz, the President of the United States is in his office now and would like to say a few words to you. Over.

NEIL ARMSTRONG: That would be an honor.

BRUCE MCCLANDLESS: Go ahead, Mr. President. This is Houston, Out.

PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON: Hello, Neil and Buzz. I'm talking to you by telephone from the Oval Room at the White House. And this certainly has to be the most historic telephone call ever made from the White House. I just can't tell you how proud we all are of what you have done. For every American, this has to be the proudest day of our lives.

Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin spent more than 21 hours on the moon. They collected samples, conducted experiments and guided the imagination to a place never seen before.

"The first tourists on the moon," Cronkite commented.

"There were the ghostly television pictures we all saw of Armstrong and Aldrin on the moon. Armstrong's first words – "A small step for man, a giant leap for mankind.' And Aldrin's two-word description, 'magnificent desolation,'" Cronkite told viewers. "Apollo 11 still has a long way to go, and so do we."

The dangerous journey home

"Man finally has visited the moon after all the ages of wishing and waiting," said Walter Cronkite.

The trip home from an impossibly distant dream was supposed to take just three days. But, in the vastness of outer space, there was a lot of room for error.

"Two Americans with the alliterative names of Armstrong and Aldrin spent just under a full earth day on the moon," Cronkite told viewers.

The most nerve-wracking moment since Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin's moon landing may well have been the moment they tried to leave. The lunar module had only one ascent engine, and hours before the scheduled liftoff, Aldrin had discovered a problem with a switch on a circuit breaker that supplied it with power.

BUZZ ALDRIN TO MISSION CONTROL: The end of it appears to be broken off.

If the engine didn't start, the astronauts would be stranded on the moon with no way home. Despite the cutting-edge technology of the time, they relied on a simple felt tip pen to activate the circuit breaker.

BUZZ ALDRIN: 9, 8, 7, 6, 5 … proceed. … We're off!

"Engine's firing," Cronkite announced. "They're on the way."

After liftoff from the moon, Armstrong and Aldrin had to link up with Michael Collins in the command module to hitch a ride back to Earth.

MICHAEL COLLINS: Houston this is Columbia … We're all three back inside.

"It was a joyous moment. It was indeed," Armstrong told Bradley. "I'm not sure Mike was all that enthusiastic about us bringing all that dirt into his nice clean spacecraft, but we did. [Armstrong laughs].

Armstrong and Aldrin had brought back about 48 pounds of lunar rock and soil.

"Now, at this point in the journey," Cronkite explained, "there are … still some critical maneuvers yet to perform."

MISSION CONTROL: Columbia, Houston. … We would like you to jettison Eagle.

The astronauts discarded the lunar module.

MICHAEL COLLINS: There she goes. It was a good one.

CBS News had been on the air for 32 straight hours.

"This concludes one of the longest scheduled broadcasts … the longest in the history of television… Thanks from Walter Cronkite, CBS News Space Headquarters, New York."

The network suspended wall-to-wall coverage, updating viewers as necessary.

Hours later, early on July 22, Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins reached another mission-critical moment.

MISSION CONTROL: We're now 15 seconds from the scheduled ignition time.

Like the Eagle, the command module had only one main engine. To break out of the moon's orbit, it had to work.

"There's a saying that trouble is most likely to occur when you least expect it and so we were guarding against getting too complacent," Armstrong told Bradley.

To get home, the spacecraft's speed and direction had to be nearly perfect. That meant igniting the engine at the right time for just the right duration.

MISSION CONTROL: Roger. We got you coming home.

"When did it first hit you how enormous the public impact of all this was?" Bradley asked Armstrong.

"We would, uh, get messages from mission control during the flight that indicated that there was widespread coverage," he replied.

Over the next two days, the astronauts made a kind of extraterrestrial video diary. Michael Collins experimented with a spoonful of water for viewers around the world.

MICHAEL COLLINS | VIDEO DIARY: Can you see the water slopping around on the top of the spoon, kids?

MISSION CONTROL: That's affirmative, 11.

But hours later as he prepared for a heroes homecoming, Collins seemed keenly aware they weren't home yet.

MICHAEL COLLINS: The parachutes up above my head must work perfectly tomorrow or we will plummet into the ocean.

MICHAEL COLLINS: The Earth is really getting bigger up here.

To safely reenter the Earth's atmosphere, the capsule had to hit it at the right speed and angle; too steep and it would incinerate. Even if everything went according to plan, the heat from air friction would cause a communications blackout.

MISSION CONTROL: And 11, Houston. You're going over the hill there shortly.

NEIL ARMSTRONG: See you later.

A helicopter from the USS Hornet was waiting more than 900 miles southwest of Hawaii.

"Splashdown should be just now…" said Cronkite.

"Apollo 11 is back from the moon, safe and sound. The crew has just reported to air boss … they're in fine shape," Cronkite continued.

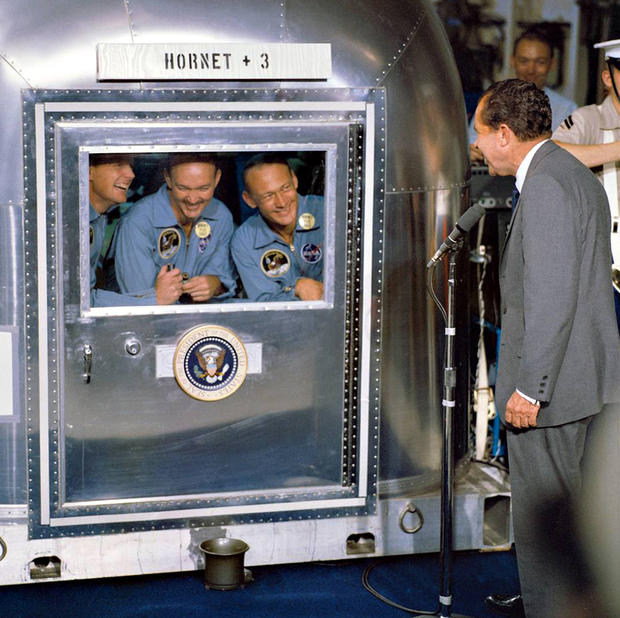

Cronkite explained, "So, covered by protective garments, these voyagers to and from the moon went into isolation."

That's because NASA didn't know if the astronauts had been exposed to anything infectious.

"What happens when you look out and you see the President?" Bradley laughed.

"It's hard to prepare for a thing like that," said Armstrong.

"Neil, Buzz and Mike," President Nixon addressed the men, who were inside an isolation chamber. "I have the privilege of speaking for so many in welcoming you back to Earth."

"We're just pleased to be back," Armstrong replied, "and we look forward to getting out of this quarantine."

So, hugging their families had to wait.

"They … will be flown, quarantine station and all, to Houston," Cronkite reported, "before finally emerging in mid-August to the hero's welcome they so richly deserve."

The world celebrates

Just weeks after Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins came back down to Earth, they took a victory lap with a day of parades across America.

"State Street is crowded with Chicagoans wishing well to the astronauts of Apollo 11," Walter Cronkite reported.

"Look at that car bogged down with confetti and wastepaper. They're knee deep in it in the back of the car. It's a good shot we haven't seen that before," Cronkite remarked of the astronauts' car filled with ticker tape during the parade.

"…all that New York has given today … is dwarfed by what you have done," New York Mayor John Lindsay told the visiting astronauts.

"We've all come a long way with these three Apollo 11 astronauts," Cronkite told TV viewers. "They've made us proud and shown us that a massive national effort can be mounted and carried through to success whether out into the reaches of space or … praise be perhaps right here on the face of the Earth."

In Los Angeles, President Richard Nixon hosted America's heroes at a state dinner.

"It was our privilege today across the country to touch America," Armstrong said at the dinner. "We hope and think that those people shared our belief that this is the beginning of a new era, the beginning of an era when man understands the universe around him and the beginning of the era when man understands himself."

After celebrating at home, the Apollo 11 astronauts took their unifying message overseas. Nations everywhere were happy to celebrate the magic of touching a world beyond our own.

It was a heady time, and some wondered how the three men of the moment would ever get their feet back on the ground.

"How do you propose to restore some normalcy to your private lives in the years ahead?" a reporter asked the astronauts at a press conference.

"I wish I knew the answer to the latter part of your question," Aldrin replied.

"Kind of depends on you," Armstrong remarked as the crowd laughed and applauded.

Apollo 11 would be Armstrong's last mission. Just two years later, he began teaching aeronautical engineering at the University of Cincinnati. The reluctant hero, who would always be known as the first man on the moon, never quite saw himself as a star.

"You sometimes seem uncomfortable with your celebrity. That you'd rather not have all of this attention," Bradley noted to Armstrong.

"No, I just don't deserve it," he replied with a laugh.

"But look, how many people have walked on the moon? Twelve? You were the first. You were chosen to do that. That's special," said Bradley.

"I wasn't chosen to be first. I was just chosen to command that flight. Circumstance put me in that particular role. That wasn't planned by anyone," said Armstrong.

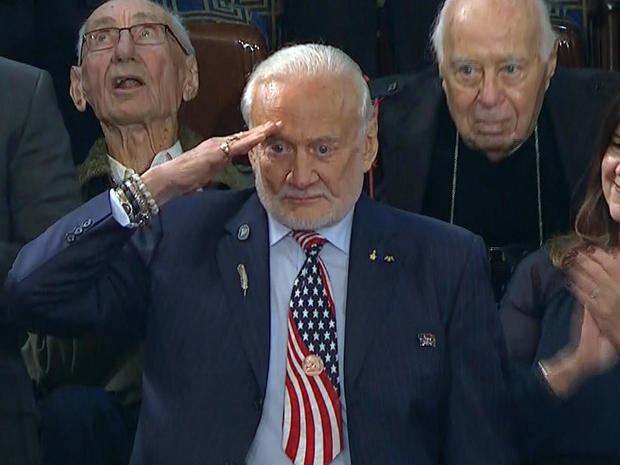

Armstrong's colleague, Buzz Aldrin, was not quite as modest. He embraced his lunar celebrity with gusto. The now 89-year-old was honored at this year's State of the Union address.

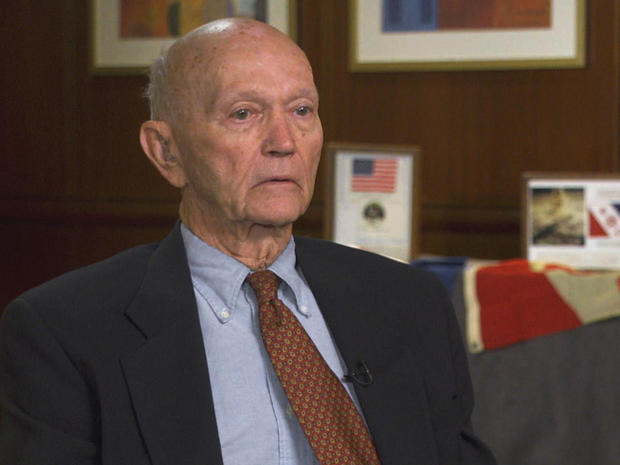

Michael Collins, who piloted Apollo 11 but never set foot on the moon, went on to become the first director of the National Air and Space Museum. His trip to the moon gave the 88-year-old Collins a surprising perspective.

"My primary recollection is not that of the moon. It is of the Earth as seen from 230,000 miles out," Collins told CBS News correspondent Mark Strassmann. "It's a fragile place. And we need to do a better job of taking care of it."

Even late in life, Armstrong never lost his great love of flying.

"Gliders, sail planes, they're wonderful flying machines. It's the closest you can come to being a bird," Armstrong told Bradley.

Neil Armstrong passed away in 2012 at the age of 82. Armstrong said, that as momentous as it was, he did not want his life to be defined by that "one small step."

Said Armstrong, "I guess we all like to be recognized not for one piece of fireworks, but for the ledger of our daily work."

Half a century after man first set foot on the moon, Mission Control sits preserved in time. The American space program has moved on; we've probed Mars and achieved other remarkable breakthroughs, but none that captivated the nation or united the world quite like Apollo 11 in 1969.

Then, as now, our nation was divided politically, our soldiers fighting far from home. When those three American astronauts blasted off toward the stars they left behind a violent and troubled world. They carried with them the hopes of a nation and that plaque that still rests on the lunar dust today. Inscribed, with these words: "We came in peace for all mankind."

In memoriam:

- Neil Armstrong: Aug. 5, 1930 - Aug. 25, 2012

- Walter Cronkite: Nov. 4, 1916 - July 17, 2009

- Ed Bradley: June 22, 1941 - Nov. 9, 2006