Mammogram study: Dense breasts won't raise cancer death risk in women

(AP) More women are getting the word that they may have breasts too dense for mammograms to give a good picture. What's not so clear is what to make of that information.

Busted! 8 mammogram truths every woman must know

This summer, New York became the fourth state to require that women be told if they have dense breasts when they get the results of a mammogram. That's because women whose breast tissue is very dense have a greater risk of developing breast cancer than women whose breasts contain more fatty tissue. Plus, it can be harder for mammograms to spot a possible tumor.

Monday, scientists reported a bit of good news about yet another question: Do denser breasts also signal a worse chance of survival? A National Cancer Institute study tracked more than 9,000 breast cancer patients and concluded those with very dense breasts were no more likely to die than similar patients whose breasts weren't as dense.

"It's definitely reassuring," said NCI lead researcher Dr. Gretchen Gierach, an epidemiologist who reported the results in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Yes, tumors might be found later in the most dense breasts, but once diagnosed they apparently weren't more aggressive or harder to treat, explained co-author Dr. Karla Kerlikowske, a professor of medicine and epidemiologist at the University of California, San Francisco, who has long studied breast density.

"That risk factor doesn't affect her ability to respond to treatment, and treatment is good," Kerlikowske said.

In fact, researchers were surprised to find an increased risk of death only in certain women with the least dense breasts - those who also were obese or had large tumors. Perhaps it has to do with increased hormones that accompany obesity, Gierach speculated, stressing that the finding needs further study.

Whatever the explanation, the research illustrates just how much more there is to learn about breast density's complex role in cancer.

"There's a large proportion of women who have dense breasts, but most of those people don't get breast cancer," Kerlikowske cautioned.

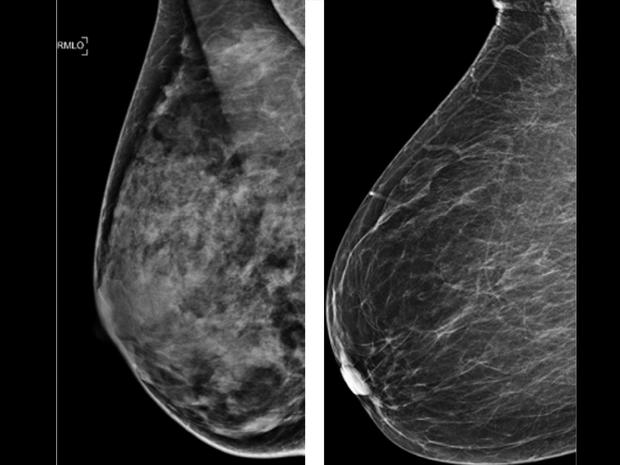

Mammograms can show if your breasts are made up mostly of dense tissue - milk-producing and connective tissue - or of fatty tissue. Fatty tissue appears dark on the X-ray. Dense tissue appears white. So do potentially cancerous spots, meaning they can blend in.

Density tends to decrease with age. Half of women younger than 50 and a third older than 50 are estimated to have dense breasts. It's not clear how many know it since mammogram providers give that information to doctors, not directly to women.

The new state laws were spurred by cancer survivors outraged that they weren't told their dense breasts might have masked the earliest signs of tumors on supposedly clean mammograms. Connecticut, Texas, Virginia and New York have passed laws requiring that mammogram providers notify women if they have dense breasts when they mail out the exam's results. Similar legislation has been introduced in other states and Congress; an advocacy group is keeping track at http://www.areyoudense.org.

The consumer conundrum: What do women do next? Other exams, such as ultrasounds or MRIs, sometimes detect tumors that mammograms miss - but there's no data showing that the expensive extra testing saves lives, one reason some doctors' groups have lobbied against some of the laws. Cost aside, those extra tests also tend to trigger more false alarms, leading to needless biopsies. California's governor cited such concerns in vetoing breast density notification there last year.

In Connecticut, insurers are required to pay if a doctor orders a breast ultrasound, and early reports suggest demand for that test is rising.

New York's new law, scheduled to take effect at year's end, sidestepped explicit next-test advice by requiring the notification to say: "Use this information to talk to your doctor about your own risks for breast cancer. At that time, ask your doctor if more screening tests might be useful, based on your risk."

Another big concern: There's no standard way to measure breast density - it's a judgment call that can vary from radiologist to radiologist, and from one year's mammogram to the next, said Dr. Otis Brawley of the American Cancer Society.

Radiologists divide density levels into four categories. According to the American College of Radiology, about 10 percent of women have almost completely fatty breasts. Another 10 percent have extremely dense breasts, the level that Kerlikowske said is linked to a higher risk of developing cancer. The rest are in between, with about 40 percent having scattered areas of density and 40 percent having fairly widespread density, categories especially difficult to classify.

"We're making policy in a gray area where the experts and doctors don't know what it means," said a frustrated Brawley.

To help women make sense of the debate, the American College of Radiology this month developed a brochure for mammography centers to distribute:

UCSF's Kerlikowske said knowing you have dense breasts could be valuable, if the information is used properly. It's one more factor to weigh along with things like whether your mother or sister had breast cancer, if you've had previous biopsies, and your reproductive history - all information that helps doctors determine your overall risk.

Beyond that, Kerlikowske is leading a major study to try to determine the best screening approach for women with high breast density and a variety of risk factors.

"I hope in a year or two we can make some intelligent recommendations," she said.

Leading medical groups offer differing recommendations on mammograms.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, a group of medical doctors who advise the government on treatment guidelines, recommend women ages 50 to 74 get a mammogram every other year.

The American Cancer Society recommends women ages 40 and older should get a mammogram every year and should continue to do so for as long as they are in good health.