Making sense of memory

As we embark on a new year, we almost can't help reflecting on the one we've left behind. But why do some moments stand out and others fade away? And even if your memory is good, is it ever accurate?

Memories make up our life stories. But experts say that as the years go by and we change and develop, our recollections adjust with us, whether we know it or not.

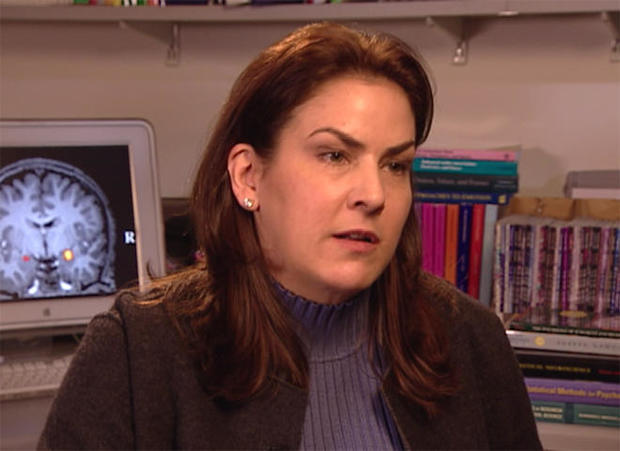

"I think if you're trying to understand the human psyche, you have to understand first and foremost, memory," Elizabeth Phelps, a research psychologist at New York University's Center For Neural Science told Sunday Morning correspondent Russ Mitchell. "I mean, it really is telling you everything about who we are … we are our memories, absolutely."

The children's game called Telephone, played by first-graders at an elementary school in New York, is commonly used by researchers to explain how memories evolve. The children were observed by Dr. Pauline McHugh of NYU School Of Medicine's Brain Health Center.

"What happens is there is a process of rehearsal," she said. "You have a very significant memory. You tend to play it over and over in your head. And every time, it can be changed and altered subtly depending on what you're feelings were about, what your past experiences were and it can end up often times with the basic elements intact but the color or the tenor of it be very, very different. What happened when, who was wearing what, who said what to whom at what time. That can be very different."

Although memories are constantly changing, Phelps said they are not always completely inaccurate. She said that memory plays an important role in guiding people through their lives.

"And what challenges you encounter at different points in your life are gonna change, right?" she said. "So you don't want the same interpretation of a memory when you're 15 you know and when your 50."

Writers David Halberstam, Gay Talese and A.E. Hotchner have been very lucky. They have spent many good times at Elaine's, a legendary Manhattan hangout. Now that they are considered among the best writers of their generation, even the struggle and self-doubt of their early years are tinged with the color rose.

"You adjust memory as you get older to make life bearable," Halberstam said. "I think what memory does is it releases you, if you're lucky, and you tend to remember the better times."

"We were here in the '60s before any of us knew what was going to happen or not happen," Hotchner said. "And it was formative, I think, for all of us that we would be here regularly and discuss our woes and our wanna-bes and almost-was."

"At that point, none of our lives were very smooth," Talese said. "And we had a tolerance for whatever problems anybody else had. We understood and dealt with them."

In fact, from a less-modest perspective, in the early '60s, all three were about to break through. Hotchner's classic memoir, "Papa Hemingway," was released to glowing reviews in 1965. Talese, who was already a prominent newspaper reporter, published his first book in 1961 and a few years after was hailed for creating what would be dubbed the new-journalism with his profiles of Frank Sinatra and Joe DiMaggio. In 1964, Halberstam received the Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on Vietnam.

They most remember the camaraderie that got them through both the turbulence and the triumphs.

"I remember in '64 in the city room of The New York Times whenever they announce the Pulitzer Prizes," Talese recalled. "And I believe, David will have to correct me, but as I recall, the information came by ticker, you know, just you're waiting. I'm like here next to Halberstam and we read, we're leaning over and then we see 'David Halberstam.'"

After decades of friendship, some memories are not so sweet. Among the worst is a feud in the 1970s between Talese and Hotchner over a tennis game.

"We were playing tennis in Chicago and we had a fight while playing. We were partners, playing doubles. It would be interesting sometime to compare notes, wouldn't it?" Talese said to Hotchner.

"He would have one version of it, and I'd have a completely different version," Hotchner said.

Indeed — experts say, like fingerprints, no two memories are identical. From the lighthearted musical, "Gigi," to the bleak novel, "Remembrances Of Things Past" by Marcel Proust, the elasticity of memory is a universal theme.

Phelps said that it's very unlikely that two people will remember the same event exactly the same way because each person comes to a situation with a different set of expectations and biases.

"When we have a memory it is a combination of what's actually out there in the world and what's going on inside of us," she said.

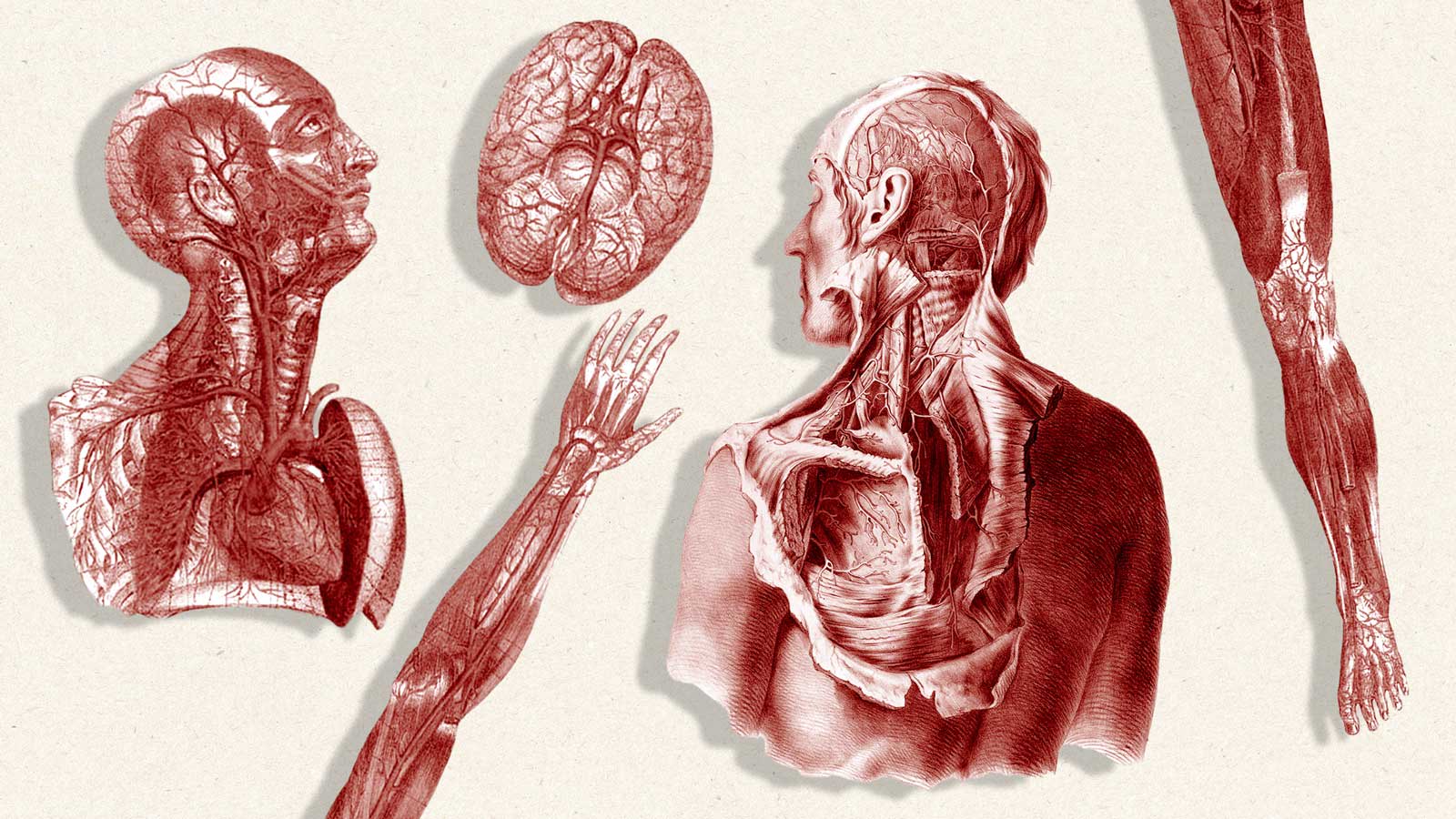

What's going on inside of us has a lot to do with this area in the middle of the brain, the hippocampus and the amygdala. The hippocampus and regions around it record two basic components of memories — episodic, or life memories, and semantic, factual memories.

"There was probably a day when you came home from school and could tell your mom, 'Guess what, today I learned that George Washington was the first President of the United States,'" Phelps said, "but you've lost those details. What you have now is the knowledge."

A bump at the end of the hippocampus, the amygdala, comes in during highly emotional events. The stronger the emotion, the more lasting the memory will be.

"You get a little bit more stressed and your memory starts increasing. You start noticing things more. You start remembering things more," McHugh said. "If you have too much stress, that starts interfering with your memory. And then you stop being able to make memories as powerfully or as accurately as you were before."

Most of us believe we have vivid recollections of the events of 9/11, the Kennedy assassination and the Challenger explosion. But researchers say those memories aren't as accurate as we think. Consider what happened after test subjects saw filmmaker Michael Moore's movie "Fahrenheit 9/11." Phelps said just seeing that movie changed how people remembered the actual event.

Hotchner, Talese and Halberstam have all navigated that murky area between history and memory.

"Nobody's memory is as exact as anybody else's about one event," Hotchner said. "It's always selective."

"All history, I think, though, is also selectivity and flawed memory blended with statistics. I mean, how accurate can the history of the Civil War be? Or WWI?" Talese said. "But then you think, one thing leads to the other, memory triggers more memory and large as a picture, it might be selective, it might be idealized or whatever it is, it's as close as we can get to the truth of ourselves."

Mitchell claimed his first memory was the day President John Kennedy was shot. He was three years old. Phelps said he probably doesn't really remember that day.

"At three years old, we actually don't remember those memories later," she said. "So probably, your memory of that is a combination of what you heard and what you saw afterwards. And you know, it was important and other people cared about it, so you formed a memory and you have that expectation that you should have that strong a memory. And that probably influences that as well."