60 Minutes Presents: Making a Difference

Welcome to 60 minutes presents. In this season of giving, we celebrate stories of Americans whose generosity extends all year long. We begin with Make-A-Wish.

If you could be anything; go anywhere; meet anyone, what would you wish for? The Make-A-Wish Foundation has been asking seriously ill children that question for more than 35 years. Make-A-Wish became famous by making dying children's final wishes come true. A child doesn't have to be terminally ill anymore to get a wish. Last year, the organization granted 15,--- wishes. They cover a broad range.

Some children get to meet famous athletes; one had much of San Francisco pretend he was Batman for a day. Another chose to jump from an airplane. We wanted to find out what leads to these wondrous moments.

Make-A-Wish is a growing organization that spent more than $200 million in donated money on wishes last year. It's headquartered in Phoenix; has more than 60 local chapters across the country and almost 40 more around the world. To see how wishes become reality, we spent time with some of its most dedicated volunteers in one of its most active chapters in the northeast corner of Arkansas. As we first reported back in 2015, we discovered a place where - despite persistent poverty - we found inspiring generosity.

They begin at dawn. One day a year, hundreds of volunteers fan out across northeast Arkansas to raise money -- at street corners, in schools...their goal:

To get enough money on this one day to grant every wish for the area's sickest children. Volunteers Christie Matthews and Danna Johnson have run this fundraiser every year since 1999.

Christie Matthews: I mean, it literally just exploded. Every year we would add another town.

Bill Whitaker: This is small town America.

Christie Matthews: They're very small towns; 600, 700 people-- a handful of change at a time.

As this day's donation deadline approaches, groups of volunteers race to the local radio station to announce their town's total -- down to the penny.

[Give me a number. $8,468.62!]

[ $25301!]

[$12,054.55!]

Trey: Golly! The big finish is just moments away, standby.

The total tally from northeast Arkansas is the big story on the 7 o'clock news.

[TV announcement: What do we have here? 323,000!]

That's 323,000 -- enough to grant more than 30 wishes -- donated from places with little to spare.

In Harrisburg, 40 percent live in poverty, but this town of 2,000 still contributed $25,000.

Bill Whitaker: The wishes were going just to children who were dying. And that's no longer the case?

Christie Matthews: We talk about it not being a last wish, but we create lasting wishes and memories that these families can take on forever.

[Christie Matthews: Hi Kaden!]

Kaden Erickson is fighting a deadly type of leukemia. At his interview as a potential recipient, he thought his wish was a long shot.

[Kaden Erickson, home visit: My number-one wish choice is to go to Australia.]

Folks here make granting the wish a big surprise. Months after his interview, Kaden thought he was getting this plaque just for being a Make-A-Wish volunteer.

[Kaden Erickson: Make-A-Wish October 11, 2014. Kaden Erickson your wish has... your wish has been granted!]

[Kendra Street: Hey Kaden, you're going to Australia!]

His mother Jeanne...

Jeanne Erickson: He was just shaking the plaque. And his little legs were just doing a little happy dance in the chair. And it was-- it was something pretty special.

Bill Whitaker: You must have been surprised?

Kaden Erickson: I was the most surprised I've ever been in my life.

Kendra Street: I'm so excited for you. You know it?

Kendra Street choreographed Kaden's surprise. When not playing fairy godmother, she's teaching at Marmaduke Elementary School. Everyone at the school chipped in to pay for Kaden's wish, many turned out to share the revelation.

[Kaden Erickson: I get to go to Australia! I get to go to Australia!]

Kendra Street: He was excited. He was grateful. And he knew what it meant for him and his family.

[Kaden Erickson: Thank you everybody.]

Kaden had endured two excruciating bone marrow transplants. When he, his parents, and four siblings hit the beach in Australia, they hoped he'd beaten the cancer. The highlight of his trip?

Kaden Erickson: Got to hold a koala.

Bill Whitaker: Did he like put his arms around you?

Kaden Erickson: He--he--it was like a hug. It was about as heavy as a baby. And it would put the claws here and the claws here and so it was like you were getting hugged by a koala. You kind of get attached to the koalas.

Bill Whitaker: Did it make you forget for a while that you were sick?

Kaden Erickson: Yes. It made me feel a little bit normal, more normal than I've been for a while.

Feeling normal didn't last long. Shortly after returning home, Kaden learned his cancer had returned--for the third time. As we settled in for our interview, his mom Jeanne adjusted the medication he needs. It's pumped into his body next to his heart.

Bill Whitaker: You're in quite a struggle with this disease.

Kaden Erickson: There are some bad things in my body that are kind of stubborn.

Bill Whitaker: I think you're kind of stubborn yourself.

Kaden Erickson: Thank you. I think.

Kaden is so stubborn, that after deliberating for a week, he decided to undergo a third, agonizing, bone-marrow transplant. The previous two were so difficult, his parents didn't want to force him to go through it again.

Bill Whitaker: How did you make that decision?

Kaden Erickson: Would I rather just die or would I have a chance of living? It was a tough decision to make.

Bill Whitaker: Because the therapy makes you feel bad?

Kaden Erickson: It can make me feel bad. It can hurt me. It could do more harm than help. So I'm just hoping this time it will get rid of it for good.

Kaden's wish-granter, Kendra Street, was devastated when she learned his cancer had come back.

Kendra Street: You have an attachment with your kids. And Kaden's one that I've really attached to. And I've gotten to keep in touch with him. And so seeing him have to go through that again. It's--it's just painful. He's just a really amazing kid.

[Let's give Kendra a round of applause.]

You see, Kendra had survived her own fight with cancer. Back when she was in high school she had her wish granted.

[Make-A-Wish is sending you to the Atlanta Braves.]

Getting to meet the Atlanta Braves was thrilling, she says, but...

Kendra Street: Not to underestimate what my wish was for me, but if I had to sacrifice having my wish to be able to give it to someone else, I would definitely be willing to give it to someone else.

Bill Whitaker: Being the granter of the wish is the better end of the deal.

Kendra Street: Absolutely. You get to give that joy. You get to pass it on to someone else.

The same chapter passed it on to Gavin Grubbs. He suffers from debilitating muscular dystrophy, and his wish was to meet race car champion Joey Logano.

The day we met them outside Charlotte, Joey took Gavin for a spin. They met five years ago and have become so close, they call or text each other every week.

[Joey Logano: Can you see anymore? (laughing)]

[Gavin Grubbs: I can't see. (laughing)]

Gavin was a groomsman at Joey's wedding. It all began back when Gavin was eight.

[Make-A-Wish is sending you to the Daytona 500!]

At a school assembly Gavin learned he'd get his wish to go to Daytona and meet his hero. Then it got better. Logano had flown to Arkansas to be part of Gavin's surprise.

Gavin may have a serious disease, but, as you'll see, he doesn't take himself too seriously.

Bill Whitaker: So Gavin, tell me, you are fighting a rare form of muscular dystrophy.

Gavin Grubbs: Yes, sir.

Bill Whitaker: How does it affect you?

Gavin Grubbs: Main thing is I don't have the strength of a normal kid my age. Obviously, I mean, I'm in a wheelchair, but it's not all sad because, I mean, you're-- when you got a disability, people give you-- people give you free stuff. People let you do cool things. I'm not saying, I take advantage of it, but yeah, I take advantage of it. And sometimes I feel a little bad for taking advantage of it, but you know it's worth it. Hanging out with this idiot. (laugh)

Gavin gives back too. He helps raise money for new wish kids every year.

Gavin Grubbs: It feels good to help other kids.

Joey Logano: That's, to me, is maturity beyond your years. You take advantage of the stuff that comes your way as you should. But you also you know, you give back--

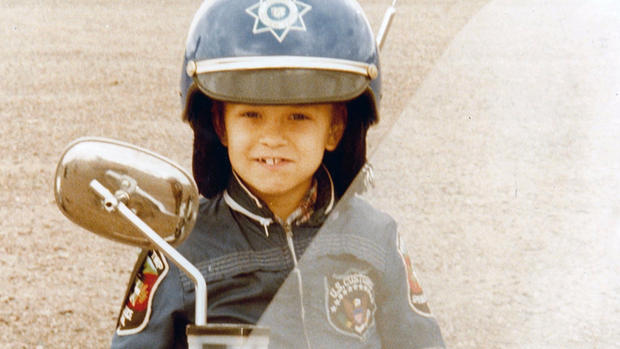

Make-A-Wish began back in 1980. Seven-year-old Chris Greicius, dying from leukemia, told his parents he wanted to be a police officer. Arizona police made him an officer for a day. The power of his wish launched a movement.

Bill Whitaker: Are there wishes you can't grant?

Christie Matthews: The one wish that's the hardest to say, "I can't do" is, "Can you make me well?" That's a tough one.

Bill Whitaker: What does that do to you?

Danna Johnson: Makes you cry.

Christie Matthews: Breaks your heart.

[Kendra Street: Thank you so much. Thank you.]

Years before she became a volunteer, getting well had been Kendra Street's first wish.

Bill Whitaker: At the time she thought her cancer was fatal.

Christie Matthews: Yes.

Danna Johnson: She was one of those that her first wish was to, "Make me well. So, I wanna live long enough for my mom to see me graduate high school." She was a senior that year.

Christie Matthews: They remind you that the little things that we think as adults are so traumatic are so small. I mean when you think about what these kids are going through--they may not see their next birthday.

Kendra saw her next birthday and since then, 14 more. Her cancer remains in remission. At Marmaduke, where she teaches, the whole school takes part in Make-A-Wish.

Kendra Street: They just understand the power of a wish. It's just--once they saw the first wish granted here, our kids wanted to help give that to someone else. We're a tiny, tiny school that's raised, last year, we raised $15,000. That's incredible. It plays a huge part of who our kids grow up to be.

[Kaden Erickson in Australia: There's a crocodile in there!]

Bill Whitaker: I don't want to overstate this in any way. But did the trip to Australia bolster Kaden's will to live?

Jeanne Erickson: Having Australia with him, having those memories, talking about that, it kind of gives him fuel to fight.

Kaden Erickson: Sometimes when I'm sad, I can think of all the happy things I did in Australia, and how amazing it was.

Bill Whitaker: You're not going to let this cancer win.

Kaden Erickson: Thank you.

You saw how courageous Kaden was. But, unfortunately, this story has a very sad ending. His cancer was relentless. Shortly after our interview, Kaden died.

Editor's Note: To support more wishes like Gavin's and Kaden's, you can contribute to Make-A-Wish, or go to wish.org to learn how to become a volunteer.

Kaden's family also asked that viewers direct donations in Kaden's name to The Ronald McDonald House of Memphis and St. Jude Children's Research Hospital in Memphis to support other kids and families in their fight against life-threatening diseases.

The Health Wagon

While the Trump administration and Republican Congress have tried to eliminate Obamacare, including the recent repeal of the individual mandate, millions of people were already unable to afford the health care exchanges. The states were supposed to help them by expanding Medicaid, the government insurance for the very poor. But 18 states declined. In those states, 4 million people are falling into a gap--they make too much to qualify as destitute for Medicaid, but not enough to buy insurance. As Scott Pelley first reported in April 2014, we met some of these people when he tagged along in a busted RV called the health wagon--medical mercy for those left out of Obamacare.

As we first reported in April 2014, we met some of these people when he tagged along in a busted RV called the Health Wagon -- medical mercy for those left out of Obamacare.

The tight folds of the Cumberland Mountains mark the point of western Virginia that splits Kentucky and Tennessee -- the very center of Appalachia -- a land rich in soft coal and hard times. Around Wise County, folks are welcomed by storefronts to remember what life was like before unemployment hit nine percent.

For more information on the Health Wagon, visit their website or call 276-328-8850

Teresa Gardner: The roads are narrow and windy curves. So it's not easy to drive the bus.

This is Teresa Gardner's territory. She can't be more than 5-foot-4 but she muscles "the bus" through the hollers, deaf to the complaints, of a 13-year-old Winnebago that's left its best miles behind it.

Teresa Gardner: Having problems seeing here.

Scott Pelley: You really can't see.

The wipers are nearly shot and the defroster's out cold.

Scott Pelley: There you go, you can see a little better now. I understand there's a hole in the floorboard here somewhere?

Teresa Gardner: Yes, it's right over there so don't get in that area.

The old truck may be a ruin but like most RVs it's pretty good at discovering America. Gardner and her partner, Paula Meade, are nurse practitioners aboard the Health Wagon, a charity that puts free health care on the road.

[How many patients do we have on the schedule today?

He was going to see what he can free up for us.]

The Health Wagon pulls up in parking lots across six counties in southwestern Virginia.

[Y'all come on in out of the rain.]

It's not long before the waiting room is packed.

[Hello Mr. Hank, how you doing?]

And two exam rooms are full. With advanced degrees in nursing, Gardner and Meade are allowed to diagnose illnesses, write prescriptions order tests and X-rays.

[Stick it out, ahhh.]

On average there are 20 patients a day, that's recently up by 70 percent. The Health Wagon is a small operation that started back in 1980. It runs mostly on federal grants and corporate and private donations.

[Blood pressure a bit high before?

Just when I get aggravated.]

Scott Pelley: Who are these people who come into the van?

Paula Meade: They are people that are in desperate need. They have no insurance and they usually wait, we say, until they are train wrecks. Their blood pressures come in emergency levels. We have blood sugars come in 500, 600s because they can't afford their insulin.

Scott Pelley: But why do they not see a doctor or a nurse before they become, as you call it, train wrecks?

Paula Meade: Because they don't have any money. They don't have money to pay for labs. They don't have money to go to an ER and these are very proud people. They, you know, you go to the ER, you get a $3,500 bill. And then what do you do? You're given a prescription, you can't fill it. That's why they're train wrecks. They have nowhere else to go.

Glenda Moore had nowhere to go but the ER when the pain in her leg became unbearable. Her job at McDonald's, making biscuits, didn't include insurance that she could afford.

Glenda Moore: The only doctor that would see me-- you had to have $114 upfront just to be seen.

Scott Pelley: What does $114 mean to your monthly budget?

Glenda Moore: Oh my gosh. That's half of my weekly pay. I make $7.80 an hour. My paycheck was about after taxes about $475 every two weeks.

The pain was from a blood clot. She needed Lovenox, a clot buster that cost about $500 for a full treatment.

[Paula Meade: Was she on Lovenox when she was discharged from the hospital?]

Paula Meade got the call from the ER, which didn't want to bear the cost. The Health Wagon had the drug for free and there was no charge for some stern medical advice.

Paula Meade: You are going to die if you don't quit smoking and it could be within a week. You need to stop now! OK?

She took the advice to stop smoking and took Lovenox but one day she felt so bad she went back to the ER.

Glenda Moore: And they did a CAT Scan and an X-ray and found the blood clot had went to my lung. But they also saw another mass on my lung. And then transported me to a bigger hospital. They found the lesions in my brain, so I was diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer and brain cancer.

Scott Pelley: What are the doctors telling you?

Glenda Moore: I start my treatment on Monday, the brain radiation, and he seemed very, I mean he seemed optimistic.

Scott Pelley: Are you hopeful?

Glenda Moore: I am. I have been. I don't know, I just feel very hopeful.

Hope, especially when the odds are long, has always been essential to survival in Appalachia. The recovery from the Great Recession hasn't arrived. In coal these days they just take the top of the mountain and you don't need many men for that. Around here a thousand were laid off in the last two years. Twelve percent of the folks don't have enough to eat. And we met them waiting for their number at Zion Family Ministries Church where a charity called Feeding America was handing out just enough to get through a week -- if you stretch. 1,654 lined up -- a parking lot of possibilities for the Health Wagon, Gardner and Meade. They've known these people and each other most their lives.

Scott Pelley: You've been together since 8th grade?

Paula Meade: Eighth grade. Yes.

Scott Pelley: Why do you do this work?

Paula Meade: Because somebody has to. You know, there's people here, you know, we always, we had dreams. We wanted to move away from here. We all, you know, we did. And then we come back and we saw the need. And actually there's a vulnerable population here that's different from the rest of America. I mean there are people, you can replicate this. But we're kind of forgotten. There's no one here to take care of 'em but us.

These patients would be taken care of in the 31 states that expanded Medicaid under Obamacare. The federal government pays the extra cost to the states for three years but Virginia and the others that opted out fear that the cost in the future could bankrupt them. So the health wagon patients we met have fallen through this unintended gap.

[Do you have insurance?

No ma'am.]

Scott Pelley: Have any of you tried to sign up for the president's health insurance plan?

Voices: No--

Scott Pelley: Why not?

Brittany Phipps: I can't afford it.

Sissy Cantrell: I can't either.

Sissy Cantrell was laid off from a head start center. She's been suffering from migraines and seizures.

[I cry for no reason at all. OK.

Have you been seeing a counselor?

No.

OK.]

She came away from the Health Wagon with medication.

[I did want to ask you....]

Brittany Phipps works more than 50 hours a week, but that's two part-time jobs so there's no insurance for her diabetes.

Scott Pelley: So you're getting your insulin through the Health Wagon?

Brittany Phipps: I am now. Yeah.

Scott Pelley: And if that wasn't available, where would you get the insulin?

Brittany Phipps: I don't know.

Walter Laney's diabetes blinded him in one eye and threatens the other. The Health Wagon stabilized him and set him up with a specialist.

[Hey Walter, this is Dr. Isaacs, how's it going?

Pretty good.

How've you're sugars been?

OK.]

Walter Laney: They got my blood sugars back under control. Before this year, I was in the hospital three, four times and this year, I ain't been in none since I've been seeing them. If it hadn't a been for them, I don't think I'd be here today.

Outside the church where they were handing out food we met Dr. Joe Smiddy, a lung specialist who's the Health Wagon's volunteer medical director.

Joe Smiddy: This is a Third World country of diabetes, hypertension, lung cancer, and COPD.

Dr. Smiddy drives a second Health Wagon, a tractor-trailer X-ray lab.

Scott Pelley: I guess they taught you something about radiology and all of that in medical school. Did they teach you how to drive an 18-wheeler?

Joe Smiddy: I did have to go to tractor-trailer school. And it took a long time.

Scott Pelley: Was that harder than medical school in some ways?

Joe Smiddy: It was very difficult to get anyone to insure a doctor to drive a tractor-trailer. The insurance companies didn't believe me.

His X-ray screen is a window on chronic, untreated disease including black lung from the mines.

Joe Smiddy: We've seen coal workers pneumoconiosis, emphysema, COPD, enlarged hearts. There's 15 of the 26 had significant abnormalities here today.

Scott Pelley: Just today?

Joe Smiddy: Just today.

Scott Pelley: But when they leave your Health Wagon, they still don't have health insurance. How do they get treated for these things that you're finding?

Joe Smiddy: We negotiate. We can talk to the hospital system. We don't leave any patient unattended. We raise money for them.

Scott Pelley: You find a way.

Joe Smiddy: We will find a way.

They found a way to get Glenda Moore radiation for her brain cancer. But she'd been a smoker for 25 years. And she died three months after our interview.

Scott Pelley: You don't like this idea of receiving charity?

Glenda Moore: No. Oh, I hate it. My dad was in the military. And when he was diagnosed with cancer, he was taken care of. And I don't know, I just always assumed, you know, that's how it would work.

Scott Pelley: Do you think things would've been different if you'd had an opportunity to go to a doctor more often?

Glenda Moore: Oh, definitely. I know it would be different.

The outreach to all the people like Glenda Moore costs the Health Wagon about a million and a half dollars a year, a third of that is from those federal grants, and the rest from donations. Doctors volunteer and pharmaceutical companies donate drugs. But when we were with them...

[We got no electricity on the health side.]

...they sure could have used a new truck battery.

[There goes.Yay! ]

Teresa Gardner: Can we give you all a free flu shot for helping us?

Man: Need a free flu shot, Beaver? Nope. Ok.

Teresa Gardner and Paula Meade apply for grants. And travel to churches praying for donations and passing the plate.

Scott Pelley: Are there days you say to yourself, "I can't do this anymore."

Paula Meade: Oh, every day. Not every day. I shouldn't say every day. There are a lot of days you get frustrated because we're writing grants till 10:00 at night. We're begging for money. And you're almost in tears because we're like, "OK, what are we gonna do," because I've got a family too. It gets frustrating, it gets hard.

Scott Pelley: It's enough to wear you out, Teresa.

Teresa Gardner: We're pretty beat down by the end of the day on most days really. But we do get more out of it then we ever give.

Paula Meade: When you look at it practically, you think, "What in the world am I thinking?" But then I have that one patient that may come in and say, "Couldn't bring you anything, can't pay anything but here's a quilt I wanna give you." And I mean when they do that and they're so heartfelt and you just-- and they put their arms around you, "I don't know what I'd do without you..."

[You're doing a lot better.]

Paula Meade: It lets you think, "OK, I was put here for a purpose."

Teresa Gardner: And you can do it another day.

[You're a blessing to us.

Well thank you all. You're blessing us. ]

Teresa Gardner: It's them and that's what touches our heart.

Since this story first aired, Meade and Gardner have a new health wagon and it's logged a lot of miles. Virginia still has not expanded Medicaid. And we have this sad news, Walter Laney died of complications from his diabetes.

Chess Country

Chess has been around for 1500 years, but until a couple of summers ago the ancient game was still mostly a mystery to the folks of rural Franklin County, Mississippi. Few had ever played chess before, many confused it with checkers. A chess board was as out of place in the county as a skyscraper. But, as Sharyn Alfonsi first reported in March, that all changed when a tall stranger arrived from Memphis to bring chess to the country, with a belief that the game could transform a community. He was initially met with bewilderment. Who was this 6'6" outsider and why would anyone come to Franklin County to teach chess? Two years later, a chess boom is underway in the unlikeliest of places.

Tucked deep in the southwest corner of Mississippi lies remote Franklin County, where the trains don't stop anymore. Half the county is covered by a national forest, the other half it seems by churches.

This is the buckle of the Bible belt. Seven thousand people live here and no one's in a hurry. There are only two stop lights in the entire county and one elementary school.

"All the statistics, everything you look at, Mississippi is the poorest. It's the dumbest. It's the fattest. We know that the rest of the nation has that conception of us."

So imagine everyone's surprise when Dr. Jeff Bulington showed up at school to teach the kids of Franklin County a new subject: chess.

Jeff Bulington: So everybody say, "Checkmate."

Kids: Checkmate.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Before Dr. B came to town, had you played chess before?

Braden Ferrell: I didn't have a clue how to move the pieces or nothing.

Donovan Moore: Only time I saw it was on TV…

Donovan Moore, Braden Ferrell, Parker Wilkinson, and Benson Schexnaydre didn't know what to make of Dr. B, as he is known, when he first appeared in 2015.

"If there are people there, it's not "nowhere." This is somewhere. It's just a somewhere that doesn't get a lot of attention."

Sharyn Alfonsi: What did you think of Dr. B when you first met him?

Benson Schexnaydre: This 12-foot man.

Sharyn Alfonsi: The 12-foot man.

Parker Wilkinson: Whenever he came into the room saying he was planning on teaching us chess, I was like, "What? Why would somebody come down here?'

Sharyn Alfonsi: In the middle of nowhere. You're a logical guy, and it doesn't seem to make a lot of sense.

Jeff Bulington: If there are people there, it's not "nowhere." This is somewhere. It's just a somewhere that doesn't get a lot of attention.

Jeff Bulington was lured to Franklin County by a wealthy benefactor, who wishes to remain anonymous. The benefactor had seen how Bulington had molded chess champions in Memphis, in one of the most distressed zip codes in America, and wondered if chess could take hold in the country.

Jeff Bulington: Where can you put the king?

He convinced Bulington to give a few demonstration lessons in Franklin County…

Bulington, demonstration: Does that stop him from coming here?

Jeff Bulington: Afterwards I was asked, so hey, what do you think? Do you think this, these kids have it? Could you have a chess program here? And I was, yeah, of course. They're as smart as any other kids I've ever met.

Motivated by the challenge, Bulington signed a 10-year contract with the benefactor and left the city for the country.

Jeff Bulington: What is he doing? He's X-raying the king.

Bulington has taught chess for the better part of 25 years.

Jeff Bulington: What's so wonderful about the bishop and why might we think of it as an archer?

He may not be a grand master, but he's a master of using chess to tell a narrative, especially with beginners.

Jeff Bulington: This is a story about a little girl, and the stranger and the little girl's daddy.

Jeff Bulington: Elizabeth and the stranger is just my adaptation of Little Red Riding Hood to the chess board.

Jeff Bulington: Elizabeth needs to get down here to E1 where school is where she can be safe.

Jeff Bulington: It involves just simply teaching how a pawn moves and a king moves.

Jeff Bulington: Oh no! Is she going to make it?

Ricky: I told you this was a bad idea!

Jeff Bulington: I remember my partner in this project saying to me, we'd have maybe 12 kids playing chess. He didn't know what to expect.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And how many kids do you have playing chess right now?

Jeff Bulington: Well, a couple hundred.

Students flock to Bulington in part because at heart he's one of them. He grew up in rural Indiana and identifies with kids who have to feed the chickens, count tarantulas as pets and have different tastes in food.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What do you like to eat?

Parker Wilkinson: Fried rattlesnake…

Sharyn Alfonsi: Fried rattlesnake…

Parker Wilkinson: If you got to my house, if we ever find a rattlesnake in a course of like a week or so, you're getting some fried rattlesnake…

"People said that country kids couldn't learn chess. We showed 'em different."

Bulington's opened up a new world to his kids…

Benson Schexnaydre: Check.

Jeff Bulington: This is a famous game by Morphy against Count Isowarde and Duke of Brunswick. It's played in Paris. This is Paris…

Bobby Poole: We teach history. We teach geography. We teach science. We teach math. We teach it all using the chess board…

Bobby Poole is a part-time preacher and a full-time assistant chess coach for Bulington. Poole says there were doubts that Bulington could succeed in Mississippi.

Bobby Poole: All the statistics, everything you look at, Mississippi is the poorest. It's the dumbest. It's the fattest. We know that the rest of the nation has that conception of us.

Parker Wilkinson: People said that country kids couldn't learn chess.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And?

Parker Wilkinson: We showed 'em different…

Benson Schexnaydre: We proved them wrong. We proved 'em wrong.

Proof came last year in Starkville, where Bulington's team of mostly elementary school kids from Franklin County faced off against much older high school players at the Mississippi state championships. Rebekah Griffin was in the fifth grade.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What was their reaction when they saw you, a little fifth grader sitting across the table from them?

Rebekah Griffin: One of them started bragging to their friends about how he got easy pickins'…

Sharyn Alfonsi: Is that a little scary, playing somebody who looked that much older than you?

Rebekah Griffin: I didn't really think about it until somebody told me, 'You played a guy with a beard?!'

Sharyn Alfonsi: You guys roll in, and they say, 'Who are these kids,' right?

Braden Ferrell: They were basically, like, trying to say we were a joke cause we were kids. But after the game, we usually beat 'em and they were like very shocked.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Don't you guys feel bad you beat all those older kids?

Braden Ferrell: Never…

Parker Wilkinson: No. I don't want that to make me seem like a cruel person, but I'm, I really am just OK with crushing people's spirits.

In the end, Franklin County dominated the state championships.

Mitch Ham: What happened is a bunch of hillbillies beat the snot out of a bunch of really highly educated, sophisticated people. So that's what happened…

Mitch Ham was among the many parents in Starkville…he thinks the victories served as a milestone for Franklin County's kids.

Mitch Ham: That was very sobering for them, to suddenly realize, 'Wow, we are good.' So them having the realization of their own potential was a beautiful moment.

Sharyn Alfonsi: How did the teachers, the other teachers, react?

Jeff Bulington: Over the course of my career in teaching chess people say things like, "I did not know that he could do something like that, or even something as simple and as crass as I did not know he was smart or she was smart," or something like that.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What does that tell you?

Jeff Bulington: It tells me some people got it wrong, that some kids have been underestimated or written off for reasons that are false.

"I feel like chess could take us anywhere. But it's not about where it takes us, it's about how far it takes us."

Chess has helped Bulington's players see there's more to themselves than they've seen before.

Parker Wilkinson: Chess is, like, something that like I'm like really good at for once.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Has it changed you at all?

Donovan Moore: It has. My grades have gone up.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Your grades have gone up?

Donovan Moore: All my grades used to be like low, medium low Bs. Now, they're A's and high B's.

Rebekah Griffin: I feel like chess could take us anywhere. But it's not about where it takes us, it's about how far it takes us.

Last year, only seven of the 93 graduates from Franklin County High School went on to a four-year college, but every chess player we spoke to plans to attend college some day.

Jennifer Rutland: It's really shocked me how far he's came…

Jennifer Rutland is Braden's mom. She runs the First and Main Café, one of the few places in the county that serves a hot meal. She believes her son won't be flipping burgers for a living.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Is it fun to see your kids dream a little bigger than the county line?

Jennifer Rutland: Yes. Yes. So big that it's almost like, "Braden, come on, get real." You know, it just gets so big….

Mitch Ham: You always want to see your kids go further. And I think chess can be a vehicle to take 'em there, you know? This gives them a window at a young age, that, 'Hey, there's a whole world out there. I don't need to set my goals at making $8 an hour, I need to set my goals at whatever I want 'em to be."

Chess has filled a social void and given Main Street a pulse.

In October, a new chess center opened in the middle of Meadville, the county seat.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Do you feel like chess has made the community more hopeful?

Jeff Bulington: Certainly parts of it, yeah, right. I mean, this flower hasn't bloomed yet. It's just starting to, right? There's a lot yet to come.

The chess center has become like a beacon in the county. Each day after school, kids who have the desire and aptitude receive more instruction from Bulington.

Jeff Bulington: So, what does black do?

They've become so immersed in the game, with its infinite number of possible moves, that when these students finish playing chess, they go home -- and play more chess….

Sharyn Alfonsi: Can the best chess player in the world come from Franklin County?

Benson Schexnaydre: Maybe…

Braden Ferrell: Absolutely.

Parker Wilkinson: Absolutely.

Benson Schexnaydre: It's super possible.

Before they could take on the world, they would have to face the nation.

The week before Christmas, 33 of Franklin County's chess wonders and their parents gathered in the school parking lot to begin a 10-hour journey to Nashville, for their biggest test yet: the national championships.

As day turned into night, Bulington and his students were lost in what they call the chess dimension…

Austen Johnson: Where are we?

Jeff Bulington: Well, I don't know where we are. We're in the middle of problem nine. That's all I know.

Preparing in their own language…

Jeff Bulington: Knight D4 attacking the queen and threatening the queen takes H3 check.

For what lay ahead: a weekend of intense chess, more than 1,500 players from 644 schools gathered in a giant ballroom at Opryland for seven rounds of chess over three days. Every grade, K through 12, was vying for a national title. The best teams come from the best schools in new york city. And two hours into the tournament, it appeared as if little franklin county was overmatched. After round one, the kids from mississippi had lost 30 of their first 32 games…

Jeff Bulington: You know, it's a real struggle and they're gonna learn to struggle at this level. And they're learning that they have to struggle at a different level than they ever have before.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What's the feeling when you walk in here as a player, as a coach, as a parent?

Jeff Bulington: It's a deep agonistic experience, right?

Sharyn Alfonsi: Deep agonistic experience?

Jeff Bulington: Yeah, it's real true competition based on skill alone, right? And you look around and you can see it in the parents' faces as much as the kids that there's something significant at stake here.

Nervous parents from other programs tried to sneak a closer peek into the ball room, desperate for any news. After their shaky start, Franklin County's players bore down taking more time, probing for openings, watching for threats. A Bulington mantra played in their heads: Let your opponent show you how they'd like to lose.

Jeff Bulington: Today is the last day, it's the hardest day…

By Sunday, with the final two rounds looming, Franklin County's fifth and sixth graders were hovering near the top 10.

Jeff Bulington: Everybody needs to fight for those points today, we need them very much.

Parker Wilkinson, Braden Ferrell and Benson Schexnaydre all delivered for Franklin County that left Donovan Moore, who was mired in a two-and-a-half hour struggle against a higher-rated opponent from Kentucky on the verge of victory, Donovan was asked for a draw. He said no. His opponent snapped…the tension of the event bursting to the surface. Donovan Moore eventually won, boosting Franklin County's fifth graders to number eight in the country.

Announcer: Making their debut to the stage, Franklin County Upper Elementary …

The sixth graders placed tenth. Two grades in the nation's top 10, only a year-and-a-half after Jeff Bulington first showed up to introduce chess to a small county in Mississippi.

Parker Wilkinson: One thing that I don't think I say enough is thank you.

Benson Schexnaydre: I was thinking the same thing.

Parker Wilkinson: For teaching us all this.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What are they capable of?

Jeff Bulington: Somewhere in the top three at least.

Sharyn Alfonsi: You think you can stick it out for eight more years in Franklin County?

Jeff Bulington: I won't even think of it as sticking it out.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What do you think of it as?

Jeff Bulington: I think of it as doing what I want to do, being in a place I like to be.