More cases of mysterious liver disease identified in children in several countries, health officials say

Health officials say they have detected more cases of a mysterious liver disease in children that was first identified in Britain, with new infections spreading to Europe and the U.S.

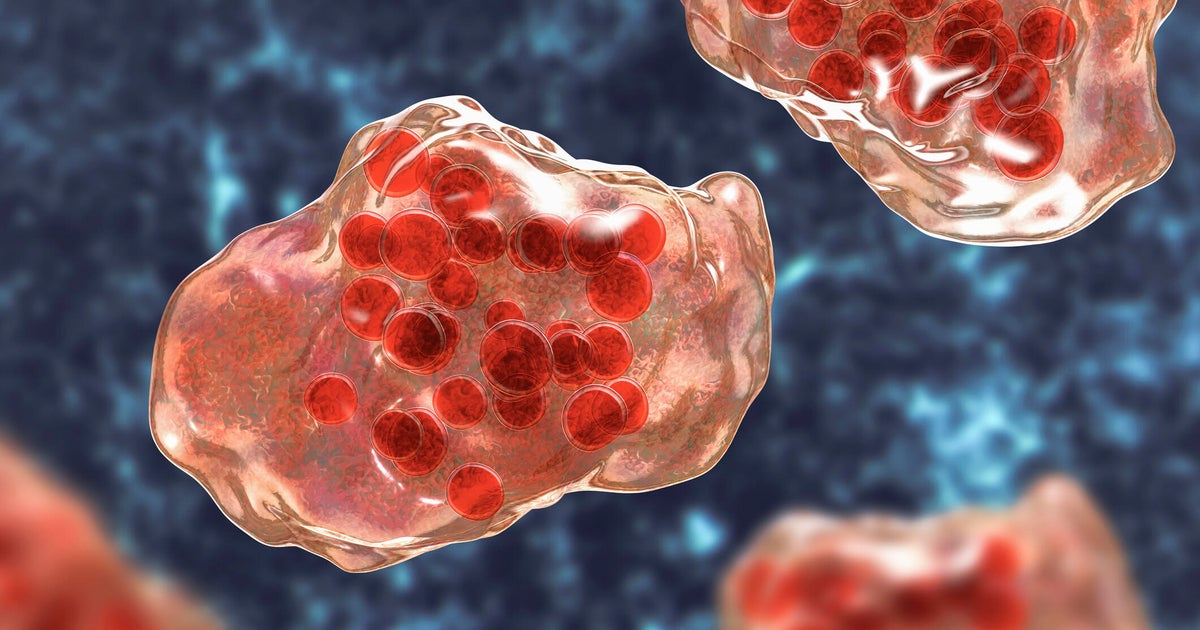

Last week, British officials reported 74 cases of hepatitis, or liver inflammation, found in children since January. The usual viruses that cause infectious hepatitis were not seen in the cases, and scientists and doctors are considering other possible sources, including COVID-19, other viruses and environmental factors.

In a statement on Tuesday, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control said additional cases of hepatitis had been identified in Denmark, Ireland, the Netherlands and Spain, without specifying exactly how many cases were found. It said U.S. officials spotted nine cases of acute hepatitis in Alabama in children aged 1 to 6.

"Mild hepatitis is very common in children following a range of viral infections, but what is being seen at the moment is quite different," said Graham Cooke, a professor of infectious diseases at Imperial College London. Some of the cases in the U.K. have required specialist care at liver units and a few have needed a liver transplant.

Cooke was not convinced COVID-19 was responsible.

"If the hepatitis was a result of COVID it would be surprising not to see it more widely distributed across the country given the high prevalence of (COVID-19) at the moment," he said.

"At present, the exact cause of hepatitis in these children remains unknown," the European CDC said.

U.K. scientists previously said one of the possible causes they were investigating were adenoviruses, a family of common viruses usually responsible for conditions like pink eye, a sore throat or diarrhea. U.S. authorities said the nine children with acute hepatitis in Alabama tested positive for adenovirus.

Some doctors have noted that adenoviruses are so common in children that merely finding them in those sickened by hepatitis does not necessarily mean the viruses are responsible for the liver disease.

British public health officials ruled out any links to COVID-19 vaccines, saying none of the affected children was vaccinated.

The World Health Organization noted that although there has been an increase in adenovirus in Britain, which is spreading at the same time as COVID-19, the potential role of those viruses in triggering hepatitis is unclear. Some of the children have tested positive for coronavirus, but WHO said genetic analysis of the virus was needed to determine if there were any connections between the cases.

It said no other links had been found between the children in the U.K. and none had recently traveled internationally. Lab tests are also underway to determine if a chemical or toxin might be the cause.

WHO said there were fewer than five possible cases in Ireland and three confirmed cases in Spain, in children aged 22 months to 13 years.

The U.N. health agency said that given the jump in cases in the past month and heightened surveillance, it was "very likely" more cases will be detected before the cause of the outbreak is identified.