Why some states face higher cancer risk

The war on cancer continues, and as some battles are won in research, others may be lost in quality of life that varies state by state.

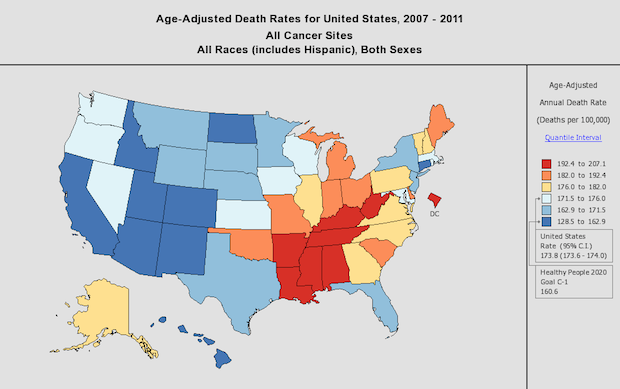

Overall, the number of people surviving cancer is rising. But people in some parts of the country have higher risk than others, according to new data from the National Cancer Institute and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. People in the South have the highest risk of dying from cancer, while people in the West have the lowest. Kentucky is the state with the highest rate of cancer deaths; Utah has the lowest.

Lifestyle factors play a key role. "The South, it's a perfect storm: many more smokers, they're obese, they're sedentary and there's more poverty," Dr. David Agus of USC's Westside Cancer Center said on "CBS This Morning."

"All of a sudden they come together and the death rate from cancer is very different from other states. And so what we need to do is [be] aware of that and start to act on that. Tobacco is still being used in many states at a very high level and that's got to stop."

Lung cancer is the leading cause of death from cancer at more than double the rate of any other cancer -- roughly 27 percent of the cancer deaths estimated for this year. Next on the list are colorectal, pancreatic and breast cancers, according to the National Cancer Institute.

Death rates are one of the most reliable indicators in progress against cancer, since they don't fluctuate as much as new diagnosis rates, which depend on how many people are screened and the effectiveness of the screening. The good news is that by 2011, overall deaths from cancer declined more than 20 percent from a high in 1991. The rates can vary dramatically by state.

Technology and research for treating cancer have made leaps in progress in recent years, though the size of the cancer problem is still enormous. At annual cancer meetings this year, doctors discussed the new approaches and how to make them more viable.

"Two major trends came out of them. One is what we call molecular target therapies: it's identifying the 'on' switch in cancer and taking a pill that turns it 'off,'" said Agus. "The second is what we call immunotherapy, which is this remarkable new kind of treatment that takes the brake off the immune system so that you can start to attack cancer."

He said both approaches buy additional time, anywhere from weeks with molecular target therapy to a year or two for immunotherapy. But one of the main challenges in getting them to more people is the cost.

"These drugs cost a hundred to a hundred and fifty thousand dollars a year and it's not sustainable," Argus added. "In today's world, we need to bring in value. We need to say, 'You have a monopoly, so you can't charge whatever you want.' But at the same time you need to be incentivized to make drugs. So we need to put the two of them in line so we can all benefit and we get new drugs"

National expenditures for cancer care in the United States totaled nearly $125 billion in 2010 and could reach $156 billion in 2020, according to the National Cancer Institute.

"We used to have five or six new drugs a year for all diseases. Now it's dozens. Technology has caused that progress curve to go like this," said Agus, gesturing upward. "So we need to respond by appropriate pricing, we need to respond by learning how to use them -- retraining the medical students with all these new technologies and at the same time giving hope to patients"