Thousands of Los Angeles teachers set to go out on strike

Thousands of teachers in Los Angeles, the second-largest school system in the U.S., are poised to go out on strike in a reprise of the wave of school work stoppages that affected a number of U.S. states last year.

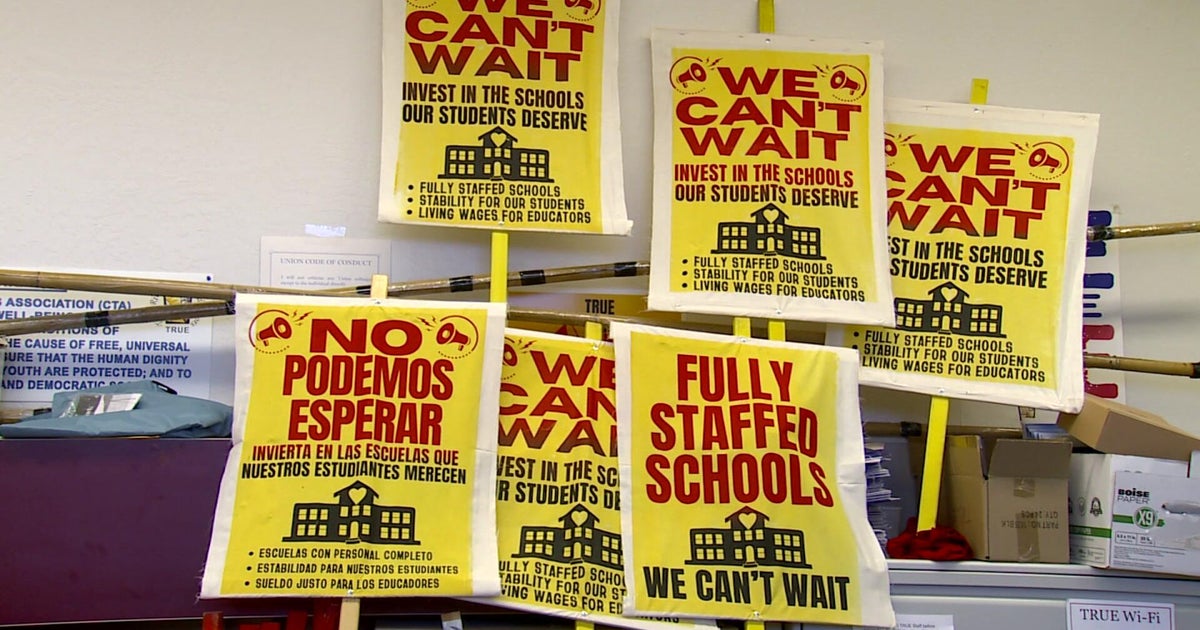

Barring an eleventh hour end to the contract dispute, more than 30,000 educators could stay out of the classroom as soon as Monday, affecting the city's roughly 480,000 public school students. A walkout had been scheduled for Thursday, but the union leading collective bargaining talks, United Teachers Los Angeles, on Wednesday afternoon postponed the action.

"We are bargaining today as well as in court. Our strike date will be Monday, Jan. 14, if no agreement is reached today," UTLA announced on its website.

The teachers in Los Angeles want higher wages and more staff to alleviate overcrowded classrooms, echoing demands made by educators in four states that staged mass walkouts in the spring of 2018. Beginning in West Virginia in February and followed soon after by walkouts in Oklahoma, Arizona and North Carolina, teachers were able to rally public support, with lawmakers in some states partially reversing course on years of cutbacks to education.

"The bigger picture was legislatures giving huge tax breaks to gas and oil while cutting funding over a 10-year period to education even as [the number of] pupils increased," Sylvia Allegretto, an economist with the University of California, Berkeley's Institute for Research on Labor & Employment, told CBS MoneyWatch. Many states never made up from their pullbacks during the recession, she added.

In Los Angeles, education officials say the union's demands could bankrupt the school system, and they plan to keep classrooms operating if teachers strike by using hundreds of substitute instructors.

By some measures, the pay of public school teachers has fallen well behind average compensation in private industry. The gap between what teachers and private-sector employees earn — adjusted for education, experience and other factors known to affect earnings — has widened considerably since the mid-1990s, according to research by Allegretto and Lawrence Mishel, a distinguished fellow at the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute. This so-called teacher wage penalty, which stood at 1.8 percent in 1994, reached a record 18.7 percent in 2017, the pair found.

As with many states around the U.S., California slashed its education budget during the recession. Since then, the state's per pupil funding has increased more than 23 percent over the last five years, according to the Public Policy Institute of California. Still, as of 2015 (the most recent year for which national data is available), California's per pupil spending of $10,786 was 13 percent below the national average of $12,346, the nonpartisan research group said.

Privatizing public schools?

The teachers' union contends that Los Angeles Schools Superintendent Austin Beutner, a former investment banker and once the Los Angeles deputy mayor, was voted in by school board members eager to effectively privatize the district by turning public schools into charters.

"We have watched underfunding and the actions of privatizers undermine our schools for too long. No more," UTLA President Alex Caputo-Pearl said in a statement announcing the Thursday strike date. "Our students and families are worth the investment, and the civic institution of public education in Los Angeles is worth saving."

Larry Sand, head of the California Teacher Empowerment Network, voiced support for Beutner, telling the Associated Press that the superintendent's business background gives him an understanding that "there's a bottom line that has to be acknowledged."

The union's goal of reining in in the expansion of for-profit charter schools in Los Angeles makes sense because funding is allocated based on the number of students in a given institution, Allegretto said. "We already have a system throughout the country. We should fix that system before we starve it of public funds and say it isn't working."

Labor energized

After declining for years, the number of strikes, work stoppages and other labor actions is on the rise. A government count identified seven major work stoppages in 2017, meaning those involving at least 1,000 workers (The Department of Labor will release a new tally in February.) But workers in education, health care, telecommunications and other industries staged much larger walkouts last year, a sign of renewed activism by unions and other labor advocates.

"There is more and more engagement and support from a broader slice of workers across the country," Allegretto said. She attributes the trend in part to stagnating wages, declining employee benefits and lack of control over one's schedule that are now issues for many Americans.

During the past year, non-unionized fast-food and retail workers took to the street to demand a living wage, leading some states, cities and companies to hike minimum pay. Separately, protests on behalf of tens of thousands of Toys R Us workers laid off without severance recently yielded results in the form of checks, while contract talks averted threatened strikes by 260,000 UPS workers, tens of thousands of casino and hotel workers in Las Vegas and about 14,000 U.S. Steel workers in eight states.

Highly paid employees in other industries have also taken to the streets to register their unhappiness. Last fall, more than 20,000 Google workers abandoned their cubicles to protest the tech giant's reported handling of sexual harassment cases, leading to a policy change.

"What we saw in the Google walkout is actually very much like what we saw among teachers in the 'red' states and the Arab Spring — moments that seem to be arising spontaneously and is the manifestation of dissatisfaction," said Lois Weiner, an education and labor expert. "People understand they have power in the workplace that they don't have as citizens."

The Associated Press contributed to this report