The Last Prisoner of the Cold War

The following is a script from "The Last Prisoner" which aired on Nov. 29, 2015. Scott Pelley is the correspondent. Michael Rey and Oriana Zill de Granados, producers.

The new opening to Cuba would not have happened without an old-fashioned swap. Cuban spies were being held in U.S. prisons. And the Cubans were holding an American named Alan Gross. Gross was a U.S. government contractor who was setting up Internet connections in Cuba. But the Cuban government said he was a spy. It has been nearly a year since Gross became the lynchpin for the diplomatic breakthrough. But why was he there? And what were his years in prison like? This is the first interview with the last prisoner of the Cold War.

Alan Gross: They threatened to hang me. They threatened to pull out my fingernails. They said I'd never see the light of day. I had to do three things in order to survive, three things every day. I thought about my family that survived the Holocaust. I exercised religiously every day. And I found something every day to laugh at.

Scott Pelley: Did you think in those early days, "Boy, the U.S. government's going to get me out of here in the next week or so."

Alan Gross: Oh, I absolutely did for the first two weeks. And then I said to myself, "Where the hell are they? Where are they?" I didn't have any idea I'd be there for five years. I knew I was in trouble. I knew I was in trouble.

Alan Gross was attracted to trouble. He's 66, a native of Maryland, an electronics specialist who spent 20 years making the rounds of war and disaster setting up communications for relief agencies.

Alan Gross: And that's why we say when we, when we would connect, when we'd align the antenna and connect to the satellite, we'd be lighting the candle. We'd light her up. And we did that in a lot of places.

In 2008, the place was Cuba. Gross was hired by the U.S. Agency for International Development. USAID is America's charity, delivering aid all around the world. But in Cuba, its mission was different. USAID asked Gross to set up independent Internet connections for the Jewish community. Only five percent of Cubans were online. But bypassing government censorship was illegal. Still Gross put together an equipment list that would do just that. The key was a device called a "BGAN satellite modem" that made a direct connection to a satellite. On his first trip to Havana, he put a piece of tape over the Hughes 9201 model number and walked his equipment through the airport.

Scott Pelley: So once Cuban customs had cleared your equipment through on that very first trip, you concluded what from that?

Alan Gross: That bringing equipment into Cuba wasn't that difficult. They had every opportunity to stop me from bringing the equipment in, they knew what that equipment was and if they didn't, you know shame on them.

In the spring of 2009, he set up two systems at synagogues. But the people he was helping warned him about getting caught. Gross wrote to his supervisors that the project was "playing with fire." It was on his third trip that he spotted trouble.

Alan Gross: I saw a van rolling down the street. And a gentleman was walking next to it with a whip antenna and it looked like a voltage meter, and essentially he was checking for radio transmissions. And he rolled right by the synagogue.

After that, Gross proposed to USAID that he add sophisticated equipment that could mask the BGAN location. He wrote, "discovery of BGAN usage...would be catastrophic."

Scott Pelley: You recognized the danger at that point, why did you go back two more times?

Alan Gross: Well, the danger didn't seem so dangerous because I came home. And I still had a contract to fulfill.

"I do believe that access to information is a right for everyone, but I have never interfered or participated in any kind of political activity overseas."

Scott Pelley: Look, you keep saying you had a contract to fulfill. That's not all that's going on here.

Alan Gross: No, that's it.

Scott Pelley: You believed in the work.

Alan Gross: I do believe that access to information is a right for everyone, but I have never interfered or participated in any kind of political activity overseas.

Scott Pelley: You were bringing free speech to an oppressed people under the nose of a government that did not want that to happen.

Alan Gross: Three billion people every day log on to the Internet around the world, how could that be circumventing the government? Now, it might sound a little bit naive. So I'm naive.

Scott Pelley: Mr. Gross, you can tell me that you...

Alan Gross: You can call me Alan.

Scott Pelley: Alan, you can tell me that you believed in what you were doing, but you can't tell me you didn't know what you were doing.

Alan Gross: I knew exactly what I was doing. I was setting up Internet connectivity for the Jewish community in Cuba. It was very simple, get 'em connected. That was it.

But it ceased to be simple on his fifth trip when four men pulled him out of his Havana hotel. He was driven to a police station where a man who seemed to be a doctor ordered him to take a pill he said was a sedative.

Alan Gross: So I took the pill, he gave me a juice box and as I'm drinking the juice box, swallowing the pill, he says, 'that's right, drink, drink." And I thought I was in an old Humphrey Bogart movie. And they took me to a hospital, they took my clothes, they gave me these striped pajamas.

Scott Pelley: You spent the night where?

Alan Gross: I spent the first night and most of the next five years at the Carlos Finlay Military Hospital.

Here, in Havana, Gross was held in a room 18 feet by 18 with two other prisoners. Every day, for the first year, he was interrogated.

Alan Gross: It was terrible. There was, it was a time of sensory deprivation for me, especially that first year. The place was infested with ants and roaches. I didn't have any meat, really, for five years.

Scott Pelley: You lost 100 pounds.

Alan Gross: Actually I lost 110 pounds.

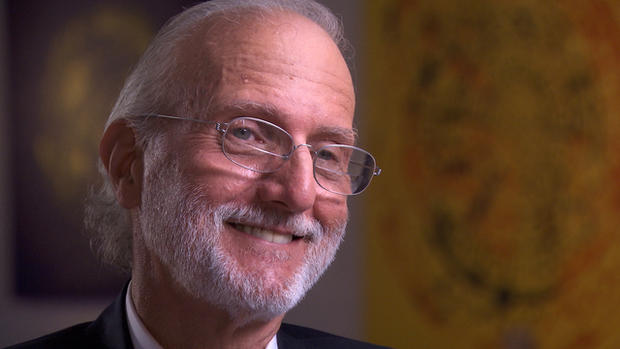

This is gross with his lawyer during his imprisonment. He lost five teeth to lack of nutrition. And yet, he says he forced himself to walk 10,000 steps a day in circles. It turned out, his legal case was on the same path. It was more than a year before he went to trial for subverting the government.

Judy Gross: I call it the kangaroo court.

His wife, Judy, was in the court.

Judy Gross: The prosecutor went on for over an hour, talking about the United States. Never mentioned Alan's name. He started, I think, with the Eisenhower administration.

Scott Pelley: The United States was on trial and Alan was Uncle Sam.

Judy Gross: Absolutely.

The sentence: 15 years.

Judy Gross: My heart sunk. Then I thought, you know, we have to start moving furiously and do everything we can.

Judy Gross held a rally every Tuesday outside Cuba's unofficial embassy in Washington. And she protested at the White House.

Scott Pelley: The worst thing that could happen would be for people to forget his name.

Judy Gross: Absolutely.

Scott Pelley: And you made sure that didn't happen.

Judy Gross: I was afraid that the government had already forgotten his name.

The government that sent Alan Gross on his mission seemed helpless. Years stretched on, Judy Gross lost their home, unable to make the mortgage.

Scott Pelley: There was a time in this imprisonment that you stopped eating.

Alan Gross: I decided that I would go on a hunger strike to protest both governments' lack of leadership and lack of effort to resolve this situation. It was ridiculous. I wasn't a spy. I wasn't a smuggler. I wasn't a criminal. "This is absolutely ridiculous. Cuba, you wanna put your finger in the U.S. government's eye? Go ahead, but leave me out of it. U.S. government, you wanna send people to countries where we have no diplomatic relations and run cockamamie programs? Go ahead, but leave me out of it, and get me the hell outta here."

One person in Washington who felt the same way was Senator Patrick Leahy of Vermont. Leahy thought USAID had bungled a project more suited to the CIA -- and he had a word for it.

Scott Pelley: Why do you say that the USAID program was stupid?

Patrick Leahy: Well, they're not a spy agency. So they shouldn't do things that make it look like that and I think it was a disservice to all the men and women who work so well for our country with USAID around the world.

In 2010, Leahy asked his top aide, Tim Rieser, to figure out what Cuba wanted for Alan Gross.

Tim Rieser: They were fed up with the USAID program. I think they also wanted a bargaining chip. They wanted their prisoners back and they wanted to make a point.

Their prisoners were celebrated in Havana as the Cuban Five. Intelligence agents, sentenced to long terms in U.S. prisons for espionage.

Scott Pelley: How hard was it for the United States to give up these five prisoners?

Tim Rieser: I can tell you that when Senator Leahy first raised this the response was it was a non-starter.

Scott Pelley: Impossible.

Tim Rieser: We're not, we're not doing anything like that. So our response was, "Well then Alan Gross is gonna die in Cuba.

Senator Leahy made two trips to Cuba. In 2013, he and his wife Marcelle met Adriana Perez, the wife of one of the five Cubans in U.S. prison.

Patrick Leahy: She said to Marcelle, "I love my husband the way you love your husband. I may never see him out of prison. I want to have his baby. Will you help us?"

Tim Rieser: We talked about it, and if there's something that we can do that the Cubans care about that isn't-- doesn't cost us anything why not do it? I talked to the Bureau of Prisons. I talked to the State Department. It became clear that there was only one option, and that was artificial insemination.

So Rieser arranged for a special delivery from the U.S. prison to a clinic in Panama. Adriana Perez became pregnant. And a new day in Cuban relations was born.

Tim Rieser: I think that was reflected in the conversations that the Cubans were having with people in the Administration also. They each remarked that the tone had changed, the, just the way they talked to each other was better.

Secret talks, of a different tone, went on for months. Gross had no idea. And he told his family he would not live another year in prison. Then came a rare phone call with his wife.

Alan Gross: And she said, "Alan, we're never gonna talk like this again. You get it?" I got it. I got it. I got it.

Scott Pelley: She couldn't say it in the clear on the phone.

Alan Gross: No. But she was very clear in her wording in her verbiage that I was coming home.

The next day, December 17th, 2014, two planes landed in Havana. One with the Cuban prisoners, the other with Senator Leahy and Judy Gross. Later that morning, President Obama announced the trade which also included an unnamed Cuban who had worked for U.S. intelligence. Diplomatic relations were reestablished after more than half a century. En route to America, Alan Gross got a call from the president.

[President Obama: And after years in prison, we are overjoyed that Alan Gross is back where he belongs. Welcome home, Alan. We're glad you're here.]

And weeks later, a shout out at the State of the Union address.

Alan Gross: I've worked in 54 countries around the world. Every time my plane would touch down on U.S. soil, I was grateful to be home, grateful. And that night, in particular, I was humbled.

Scott Pelley: You know, I'm curious. What did you say to your captors on leaving?

Alan Gross: Hasta la vista, baby.

Scott Pelley: Seriously?

Alan Gross: Seriously.