Lake Mead's water level has never been lower. Here's what that means.

The American West is facing its most severe drought in human history. Research suggests conditions are drier now than they have been for at least 1,200 years, and, compounded by the effects of climate change, will likely persist for another decade.

Communities across the region are contending with the consequences of less water. Unmanageable wildfires have burned millions of acres of land as crops withered and air quality declined. But mounting concerns about the mega-drought seemed to reach a peak in recent months, when its repercussions became startlingly clear at Lake Mead.

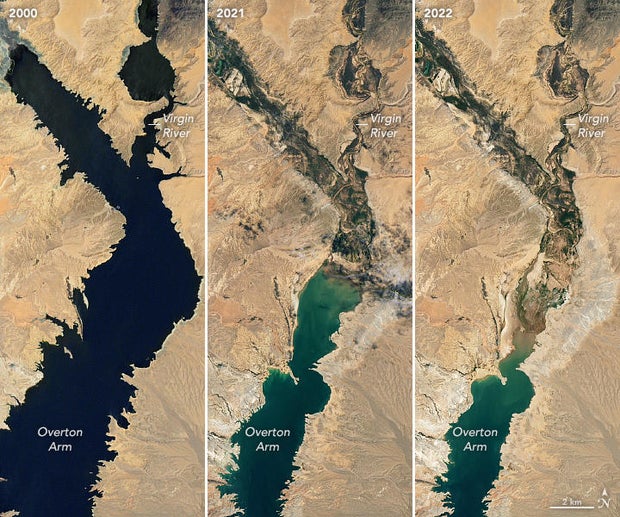

The reservoir, the country's largest by volume, sank to record-low elevation levels this summer. Photos revealed cracked earth and barren canyons while satellite images showed the reservoir's shrinking shorelines from space.

Missing persons cases reopened after human remains resurfaced in the receding reservoir on five separate occasions — a sunken World War II-era boat and schools of lifeless fish turned up as well — and fears that Lake Mead could soon sink to "dead pool status" prompted unprecedented cuts to multiple states' water supplies. This was the second round of water cuts imposed since a shortage was declared last year in the river's lower basin, where resources have historically been stretched quite thin. It comes as federal demands loom for more significant cuts to stave off a catastrophic deficit.

Where is Lake Mead?

Located along a stretch of the Colorado River, Lake Mead spans hundreds of miles over the border of eastern Nevada and western Arizona. It works conjunctively with Hoover Dam to supply water and power to 25 million people, and is a lifeline for major cities and agricultural hubs throughout the region.

Hoover Dam created Lake Mead. Its construction during the Great Depression was fundamental to the development of surrounding regions whose dry, arid climates had limited possibilities for urban and industrial expansion until then.

Water in Lake Mead has to remain above a certain elevation to pass through Hoover Dam, a process that facilitates the distribution of water as well as generates hydroelectric power to water and irrigation districts as well as municipalities across Arizona, California, Nevada and Mexico. The elevation level also determines how much hydroelectric power is generated by Hoover Dam. When reservoir levels are low the dam's ability to generate power falls too. Michelle Helms, a spokesperson for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, told CBS News that Hoover Dam's maximum capacity for power generation was 1,320 megawatts last week, which is 36% less power than the dam can usually produce.

What is the Colorado River system, and why is it so important?

Both Hoover Dam and Lake Mead are integral components of the complex system that divides and allocates the Colorado River. The river stretches 1,400 miles from Colorado's Rocky Mountains to the Gulf of California, and provides water to roughly 40 million people in the U.S. and Mexico. It supports dozens of indigenous tribes and 11 national parks, and irrigates 5.5 million acres of farmland.

A few hundred miles upstream, the Glen Canyon Dam created another critical reservoir called Lake Powell, which, together with Lake Mead, collects and stores a significant portion of the water sustaining the Colorado River system. Loss of power from Glen Canyon Dam during a season where energy consumption typically increases, like the summer, could destabilize the surrounding power grid, according to a report by the energy watchdog group NERC.

Why is there a water shortage?

Following years of steady decline, Lake Mead plummeted to its lowest elevation since 1937, when the reservoir was filled for the first time, in July. At 1,043 feet above sea level, the number recorded at Hoover Dam came dangerously close to the 1,000-foot threshold required to operate its hydropower turbines. Water elevation at Lake Powell, which feeds hydropower turbines at Glen Canyon Dam, stood at 26% of its total capacity, while the capacity of the Colorado River as a whole was just 10% higher.

Less water is flowing through the Colorado River system because of a persistent upper weather pattern that hangs over the West, Greg Postel, a meteorologist at The Weather Channel, told CBS News. The weather pattern does not bring consistent rain to certain areas beneath it, like parts of California and Nevada.

"That upper-level pattern is something that climate scientists believe is going to become more and more prevalent in a warming world, with climate change," Postel said, noting that seasonal fluctuations, like the periods of unusually heavy rain recorded this year, can still occur while the overall pattern remains in place. "In other words, we're kind of stair-stepping our way toward drier times."

Prolonged periods of lower precipitation mean there is less water collecting in Lakes Mead and Powell, and less snowpack in the Rocky Mountains to melt during warmer months and push the river downstream. Plus, because too much water was allocated when the Colorado River Compact determined state's distributions a century ago, there has historically been less of it moving freely through the system than the agreement originally suggested.

Originally, states were allowed to take a set amount of water each year from the river — an amount that allowed states to build and expand over the better part of a century. But that was based on what scientists later realized was a flawed estimate of the river's flow, and development outpaced the water available to support what's there.

How does the water shortage affect states?

The U.S. Department of Interior declared a water shortage on the lower basin last year, mandating cuts for the first time under emergency guidelines drawn up in 2007 in response to the drought.

The cuts, under a Tier 1 shortage, primarily fell on Arizona and Nevada, which will again face substantial reductions in water allocations as Tier 2 shortage requirements take effect in 2023.

Reacting to what it called "critically low reservoir conditions" at Lakes Mead and Powell, the Interior Department announced escalated cuts earlier this month. Arizona is set to receive 21% less water than it is normally allocated next year, while Nevada and Mexico lose 8% and 7% respectively.

The water shortage has already led to practical changes as states take serious steps to conserve resources, with more than $12 billion from President Joe Biden's infrastructure law and recently passed Inflation Reduction Act meant to improve western water and power infrastructure and address challenges brought on by the drought. In southern Nevada, "water cops" survey neighborhoods for waste violations and decorative grass has been banned. In Arizona, a majority of the reduction is taken from a canal that supplies water to 80% of the state's population, and without which the central agricultural sector, as well as cities like Phoenix and Tucson, could not have developed to scale.

California avoided federal reductions both years. The state receives the largest annual allocation from the Colorado River, which provides between a quarter and a third of the total water supply to its southern region. Water diverted from the river through two massive canals that feed into Southern California provide irrigation and hydroelectric power to the 600,000 acres of farmland across the region. Even without federal cuts, California's agricultural sector is facing huge losses because there is less water.

"Even though California right now is not receiving a cut in its water allocation, resources are very stretched out in California, in Southern California," Samuel Sandoval Solis, an associate professor at the University of California—Davis and a cooperative extension specialist in water, told CBS News.

As runoff from northern California fell, state irrigation districts sent less water to southern counties. Mallika Nocco, a cooperative extension scientist researching drought irrigation and a colleague of Solis, said that some farmers are experimenting with conservation practices as their allocations fall, and many are deciding to reduce their acreage and produce fewer crops instead.

"I work with processing tomato growers a lot, and I know that there are just less processing tomatoes being grown in California because of the drought this year," Nocco said. She and Solis both said farmers likely face the greatest consequences of the water shortage in California.

"Perhaps the consumers going to the market may not feel that much of the burden," said Nocco. "Who's actually feeling the burden is the farmers, the farm owners and the farm workers, because they did reduce the production, reduce the amount of income coming, reduce the number of salaries. And that's the bottom line for them, right?"

Correction: This article has been updated to note the region of California that receives water from the Colorado River is Southern California, not the Central Valley.