Prosecutor Kim Gardner's fight to reform the St. Louis justice system

This past week, former Officer Derek Chauvin went on trial in Minneapolis, accused of the murder of George Floyd. Watching on a knife-edge is St. Louis, Missouri, where demands for police reform have been growing since 2014, when Michael Brown, an unarmed Black teen, was shot dead by a White cop in a nearby suburb. St. Louis has one of the highest rates of police shootings in the country, and Black mistrust of police runs deep. So when an African American woman won the top prosecutor's job – first in 2016, and again this past November – many hoped for change. Kim Gardner, a Democrat in a Red State, promised to hold police to account. Instead, she has run into relentless opposition from the police union and its powerful allies. We went to St. Louis to find out what happens when a reformer takes on the status quo.

Kim Gardner: We as law enforcement have to hear the cries for help in the community and deliver. And that's why I'm not gonna back down. That's why I'm not gonna kiss the ring of the status quo to keep it a certain way.

Inside the Old St. Louis Courthouse, where enslaved African Americans once sued for their freedom, Kim Gardner felt the weight of expectations to keep her promise and rebuild the justice system around fairness.

Kim Gardner: It's about the will of the people. And the people of City of St. Louis overwhelmingly voted me in to do my job to reform a system that we all know is beyond repair. It needs to be dismantled and rebuilt.

Bill Whitaker: What is at stake here?

Kim Gardner: The integrity of the whole criminal justice system.

She went right to work. She stopped locking up non-violent offenders, dropped low level drug cases and ended cash bail - a system that hit Black citizens hardest. But less than a year into the job, her hopes of building trust in police suffered a setback.

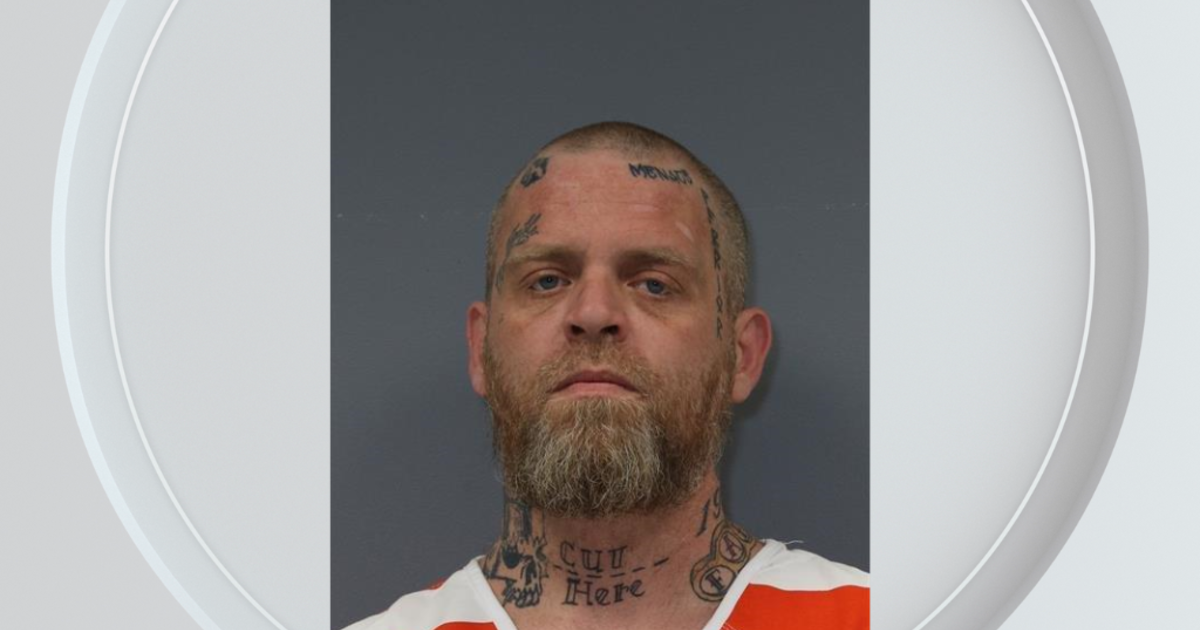

Jason Stockley – a White officer – was charged with the murder of a Black man, a drug suspect who fled. Dash cam video caught Stockley swearing to kill him. Moments later, he did. Only one gun was found. It was covered with Stockley's DNA, and none of the victim's. Stockley claimed self-defense – and was acquitted.

Protesters poured into the streets, years of mistrust and rage boiled over.

The clashes triggered dozens of police brutality lawsuits. Text messages released in court showed some officers spoiling for a fight. "Let's whoop some ass" texted one. "It's going to be fun beating the hell out of these s***heads" read another.

Kim Gardner told us for many St. Louisans the Stockley verdict reinforced a belief that city police often act with impunity. She called on City Hall to fund an independent team to investigate police shootings. It made her instant enemies.

Bill Whitaker: So right off the bat, you've not gotten along with the police union.

Kim Gardner: No.

Bill Whitaker: --from day one.

Kim Gardner: We work well with everyday police officers, every day. But what we have is the police union who basically injects fear and misinformation in the police department.

The union called her a cop hater, and successfully lobbied to torpedo her reforms at City Hall. It's gone downhill from there.

Kim Gardner: This is not all police. This is not everyone in the system believes this. But we have to have the good people stand up. Because silence is also complicit agreement with this type of behavior.

St. Louis is a city divided. The northside is predominantly Black, manufacturing jobs have gone, it has some of the poorest neighborhoods in the country. But cross to the south, it's like a different city—Whiter, more affluent, there are private, gated communities like the McCloskeys' neighborhood.

The couple vaulted to national attention last summer when they brandished guns at Black Lives Matter protesters. When Kim Gardner charged the couple with unlawful use of weapons, she came in for a storm of criticism. The McCloskeys pleaded not guilty.

Kim Gardner: I was sent emails and that said I should be hung up by a tree by the KKK

Bill Whitaker: This is just from like the last week, a week's worth of hate mail?

Kim Gardner: Uh-huh.

Bill Whitaker: This one the subject line is "Racist". "You racist piece of s***. I wish someone would put a bullet in your head." Is this common?

Kim Gardner: Unfortunately it is when it comes to me

Bill Whitaker: Another one. "I hope people destroy your neighborhood, threaten your family and more, you f***ing porch monkey." What do you think when you open up your mail and you have something like this?

Kim Gardner: Well, I think about the people who paved the way for me to even be in this position.

Bill Whitaker: Some of these are death threats. Does that frighten you?

Kim Gardner: Well, you know, I signed up for this. But what frightens me is now that's it's calls to my family, and I'm afraid that a loved one may be harmed because I took this job.

Kim Gardner grew up above her family's funeral home in north St. Louis. She got a degree in nursing, but switched to law after her brother was sentenced to 17 years in prison for robbing a neighbor's house. Crime and tough punishment are an all too familiar part of life on the North Side.

Kim Gardner: Let's start addressing the pain. Let's start addressing and really understanding the communities and those people are hardworking individuals who are not anti-police at the same time they want fairness and justice under the laws.

Bill Whitaker: People say that you are the prosecutor for Black St. Louis?

Kim Gardner: I protect all people in the City of St. Louis. And I'm not just a prosecutor for African American people.

Jeff Roorda: We have an out of control murder rate, and an out of control violent crime rate. That's what's unfair.

Jeff Roorda has been the public face of the police union for a decade. Choosing his words carefully, he told us Kim Gardner is in over her head.

Jeff Roorda: She's a prosecutor that wants to second guess everything law enforcement does. And find fault when there's no fault to find.

Bill Whitaker: So Kim Gardner is the problem?

Jeff Roorda: She's not the only problem by any stretch of the imagination, but she's not a partner with law enforcement.

But away from our cameras, on talk radio, Jeff Roorda was less restrained.

Jeff Roorda On 97.1 Radio: I keep hearing this nonsense about she has this criminal justice reform agenda, but it's just amnesty for the most vicious criminals in America. We're the deadliest city in America and she thinks that the problem is we're not nice enough to murderers, and heroin dealers and rapists?

A former suburban cop, Jeff Roorda was fired in 2001 for falsifying a police report. On the fifth anniversary of Michael Brown's death, Roorda tweeted "happy alive day!" for the White officer who shot the Black teen. Roorda told us it was to show solidarity with police who he says are being vilified all across the country.

Jeff Roorda: What we've found is that in the vast majority of these cases, it's the aggression on the other side of that encounter that results in deadly force being used.

Bill Whitaker: We've seen the videos. George Floyd wasn't doing anything aggressive. Breonna Taylor was in her bed.

Jeff Roorda: So a lot of this is problems with training, with police policies, and that's a problem we oughta be addressing.

Bill Whitaker: St. Louis has by far the largest number of police shootings in the country per capita. Why is that?

Jeff Roorda: Well, we don't shoot, Bill, we shoot back. I mean we live in a very violent city. And I don't think it should surprise anybody that sometimes the police who are trying to disrupt that violence become the victim of that violence.

Despite Kim Gardner's mandate, she's had a rocky run. Her reforms triggered a record turnover of attorneys on her staff; St. Louis' murder rate is at a 50-year high. State Republican lawmakers blame her and tried to strip away her authority.

In an unprecedented move, she sued Jeff Roorda, the police union and the city, using the Reconstruction Era Ku Klux Klan Act to claim a racist conspiracy was preventing her from doing her job.

More than 60 law enforcement officers signed a statement backing Gardner. Six Black women prosecutors flew in to support her.

Megan Green: We've been arresting people and locking them up and arresting people and locking them up for decades, and it hasn't worked, and it's not working. So it's time to do something different.

Megan Green told us she hears complaints about police from her constituents in the more affluent south. One of a handful of reformers on city council, she knows what Kim Gardner is facing. When Green questioned the police budget, the union mounted a campaign to unseat her.

Megan Green: It was to send a message to other elected officials. Like "Don't you dare, don't you be talking about how much money goes into the police department. Because if you do this is what we're going to do to you.

Bill Whitaker: So what is the prognosis for reform?

Megan Green: It's really difficult. They fight reform tooth and nail. And the tactics used to you know against elected officials are designed to quell dissent. And I think that it scares a lot of folks

Robert Ogilvie: I wish there was an easy fix to this thing. But I think it's gonna take a lot of people crossing the aisle and changing.

We met Sergeant Robert Ogilvie in North St. Louis, his beat before he quit the force in August. After 30 years, he had become disillusioned.

Robert Ogilvie: I believe that most of the officers that come out of the academy are – they all have the – the same heart that I did coming out. They wanna come out here and do a good job. But the reality out here is this-- you're basically judged by how well you are at making arrests. That's the bottom line.

Bill Whitaker: You couldn't stomach being a policeman anymore.

Robert Ogilvie: Yeah, I couldn't do it anymore. I was seeing the same thing over and over again. It just gets too much for me.

Just as the city is divided Black and White, so, Robert Ogilvie told us, is the way justice is meted out. He says police patrol with a heavier hand on the North Side – and that has to change. So, he has joined Kim Gardner's reform program to keep Black youth out of prison.

Bill Whitaker: Roorda says he's all for--

Robert Ogilvie: *Laughs*

Bill Whitaker: --reform

Robert Ogilvie: Ok.

Bill Whitaker: You laugh.

Robert Ogilvie: I'd like to see him do it. I'd like to see him step up and do something. I'd like to see what his version of reform is--

Bill Whitaker: You think he's part of the problem

Robert Ogilvie: I think he's part of the problem, yes. I think the whole – the system as a whole is a problem.

Case in point: hundreds of racist slurs were found on Facebook, posted by 43 St. Louis police officers. There were also modified images of the vigilante "Punisher," a blue line added for police. Jeff Roorda told us the incident was overblown.

Jeff Roorda: Now many of those all they had was like, comic book, like "The Punisher", or you know something benign like that--

Bill Whitaker: You do know that the "Punisher" image is being used by white supremacists?

Jeff Roorda: Well, I mean, that doesn't mean that that's why the officer put it up there. I mean, it means different things--

Bill Whitaker: What kind of message does that send to Black citizens of St. Louis?

Jeff Roorda: I mean, I think that that's, you know, a very small percentage of the members I represent.

Two officers were fired for the Facebook posts. Kim Gardner put the rest on an exclusion list, blocking them from pursuing cases or testifying in court. She told us she couldn't trust their work was unbiased.

Bill Whitaker: The police union says the exclusion list is dangerous – the reason being that they say it means that fewer cases will get to court?

Kim Gardner: Well, that's simply false. The police union is so out of touch with reality that listening to them is just not even productive.

Just as we finished speaking with Kim Gardner, word came her lawsuit claiming a racist conspiracy had been dismissed. The judge called it nothing more than "a compilation of personal slights." But Gardner told us it won't stop her. The voters of St. Louis have called for reform, and she intends to deliver.

Produced by Heather Abbott. Associate producer, Tadd J. Lascari. Broadcast associate, Emilio Almonte. Edited by Daniel J. Glucksman.