Kepler-452b: What it would be like to live on Earth's "cousin"

Kepler-452b may be Earth's close cousin, but living on the newfound world would still be an alien experience.

A group of pioneers magically transported to the surface of Kepler-452b -- which is the closest thing to an "Earth twin" yet discovered, researchers announced July 23 -- would instantly realize they weren't on their home planet anymore. (And magic, or some sort of warp drive, must be invoked for such a journey, since Kepler-452b lies 1,400 light-years away.)

Kepler-452 is 60 percent wider than Earth and probably about five times more massive, so its surface gravity is considerably stronger than the pull people are used to here. Any hypothetical explorers would thus feel about twice as heavy on the alien world as they do on Earth, researchers said. [Exoplanet Kepler 452b: Closest Earth Twin in Pictures]

"It might be quite challenging at first," Jon Jenkins, of NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California, said during a news conference yesterday. Jenkins is data analysis lead for the space agency's Kepler spacecraft, which discovered Kepler-452b.

But visitors to the exoplanet would probably be able to meet that challenge, said former astronaut John Grunsfeld, associate administrator of NASA's Science Mission Directorate. After all, he said, firefighters and backpackers routinely carry heavy loads, mimicking (albeit temporarily) the effect of increased surface gravity.

"If we were there, we'd get stronger," Grunsfeld said. "Our bones would actually get stronger. It would be like a workout every day."

The high-gravity environment would probably lead to significant changes in the bodies of Kepler-452b colonists over longer time spans, he and Jenkins said.

"I suspect that, over time, we would adapt to the conditions, and perhaps become stockier over a long period of many generations," Jenkins said.

Other features of life on Kepler-452b would be more familiar. For example, the exoplanet orbits a solar-type star at about the same distance at which Earth circles the sun. [Living on Other Planets: What Would It Be Like?]

"It would feel a lot like home, from the standpoint of the sunshine that you would experience," Jenkins said. Earth plants "would photosynthesize, just perfectly fine," he added.

Imagining other aspects of life on Kepler-452b requires much more speculation, since it's too far away to get a good look at. Researchers suspect that the planet is rocky, like Earth, but they don't know for sure. Kepler-452b probably has a thick atmosphere, liquid water and active volcanoes, but these are best guesses based on modeling work.

Models also suggest that Kepler-452b might soon experience a runaway greenhouse effect, similar to the one that changed Venus from a potentially habitable world billions of years ago to the sweltering hothouse it is today, researchers said.

Kepler-452b's star is apparently older than the sun -- 6 billion years, compared to 4.5 billion years. It's thus in a more energetic phase of its life cycle than the sun is; indeed, the star is about 10 percent larger and 20 percent brighter than Earth's sun. (That means the sunlight on Kepler-452b, while familiar to explorers from Earth, would not be exactly equivalent.)

The increased energy output of its sun might currently be causing Kepler-452b to heat up and lose its oceans -- if the planet does indeed harbor oceans -- to evaporation, subsequent breakup by ultraviolet light and atmospheric escape.

Such a scenario likely won't occur on Kepler-452b for another 500 million years or so, assuming estimates for the planet's size and the star's age are accurate, Jenkins said. (The stronger gravity of larger planets allows them to hang on to their surface water for longer periods of time in such situations than smaller worlds can.)

"But, you know, we don't know exactly," Jenkins said.

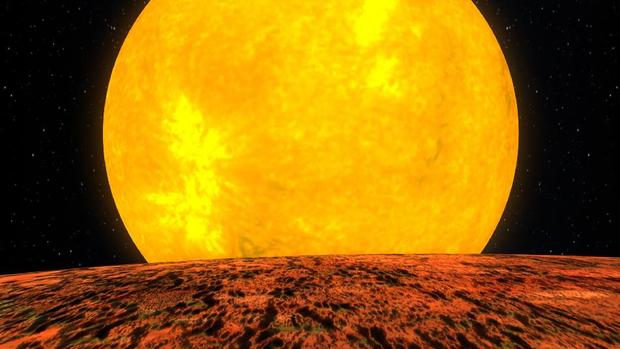

So he and other members of the discovery team helped devise an artist's concept that imagines how Kepler-452b would look if a runaway greenhouse effect were beginning to unfold.

The illustration shows "not oceans, but residual bodies of water that are highly concentrated in minerals after the oceans are largely gone, and you have lakes and pools and rivers left," Jenkins said.

"It's a fascinating thing to think about, and I think it gives us an opportunity to take a pause and reflect on our own environment that we find ourselves in," he added. "We've been lucky and fortunate to live in a habitable zone for the last several billion years, and we'd like that to continue on."