Kentucky jail using new drug treatment for inmates addicted to opioids

COVINGTON, Ky. -- Every jail is full of stories.

“Me and my brother we turned to stealing and doping,” one Kenton County, Kentucky jail inmate said. “Being a drug addict was something I thought I needed to be,” said another.

While the stories the inmates are telling may not sound like it at first, they are all stories of hope.

Jeremy Westerman is serving seven years for dealing drugs to support his own opioid habit.

“You come in here, your hope comes back. You get your wits back,” he said.

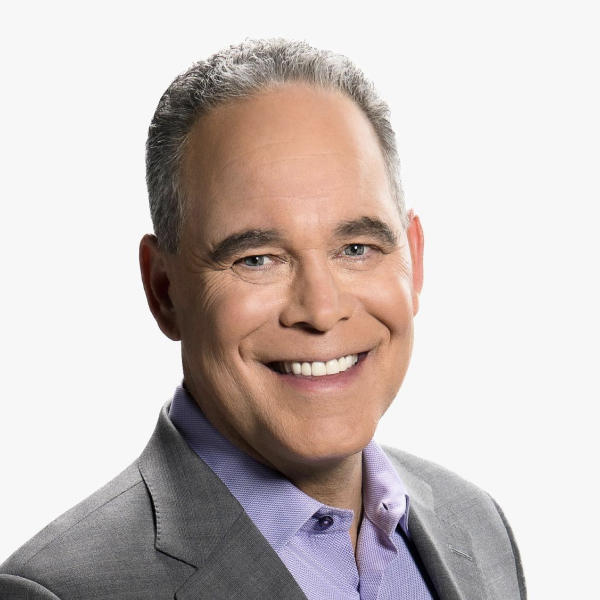

Jason Merrick is a reformed addict and former inmate who took hard lessons and translated them into a new substance abuse treatment program, an innovative approach to kicking opiates for good.

Merrick said it is easy to identify inmates that are in jail because of an opioid addiction. “Eighty-three percent of our intakes are directly or indirectly related to substance use,” he said.

Merrick combines the traditional tools of psychotherapy and 12-step support groups with a new one: Inmates are given an injection of the drug Vivitrol just before they’re released and then once a month after they get out.

“Essentially it blocks the effects of opiates, including heroin, morphine, oxycodone, for up to 30 days,” Merrick said. “If they take a normal dose of heroin, they will not feel the effects.”

Vivitrol, he said, gives them a fighting chance when they reintegrate into society.

“Once you are released from Kenton County, you have a 70 percent chance of coming back here,” Merrick said.

But for inmates in his program, the recidivism rate drops to ten percent. “This is what keeps people safe while they’re building those foundations of recovery,” he said.

Not even a near-fatal overdose kept Jordan West from using again. He eventually ended up in the Kenton County jail for 90 days on a possession charge. He signed up for the program, and the Vivitrol.

“Before my perspective was, when I wasn’t on this stuff, it was, ‘drugs, drugs, drugs. Who can I manipulate? Who can I steal from? Who can I lie to? Who can I deceive?’” West said.

“And with this Vivitrol, when it’s blocking the cravings, it’s, ‘What can I do for the next man? How can I help somebody else out?’”

Jail offers addicts a shot at getting clean, and Vivitrol offers a chance of staying clean. West is now back in school.

“It’s all about the steps you take when you get out. If you get out and you keep on doing the same things, you’re going to keep on getting the same results. It’s called insanity,” West said.

If the inmates in Kentucky are as successful as West, families and neighborhoods devastated by the epidemic of opiate addiction may finally have a way to combat it.

“Giving them that extra level of support is essential to keeping them alive and building stronger communities.” Merrick said.

Vivitrol is designed to be taken for a year or two after release while the addict gets on his or her feet. Since February, 22 Kenton County inmates have completed this program and none have re-offended. That is why the white house is considering it as a model for prisons nationwide.