Jury selection begins in Bill Cosby retrial amid #Metoo movement

NORRISTOWN, Pa. -- Jury selection is set to begin Monday in Bill Cosby's sexual assault trial in a cultural landscape changed by the #MeToo movement, posing new challenges for both the defense and the prosecution. Experts say the movement could cut both ways for the comedian, making some potential jurors more hostile toward him and others more likely to think men are being unfairly accused.

"We really have had this explosion of awareness since that last trial and it has changed the entire environment," said Richard Gabriel, a jury consultant who has worked on over 1,000 trials. "It is a huge challenge for the defense, but it could also provide an avenue and open up the topic."

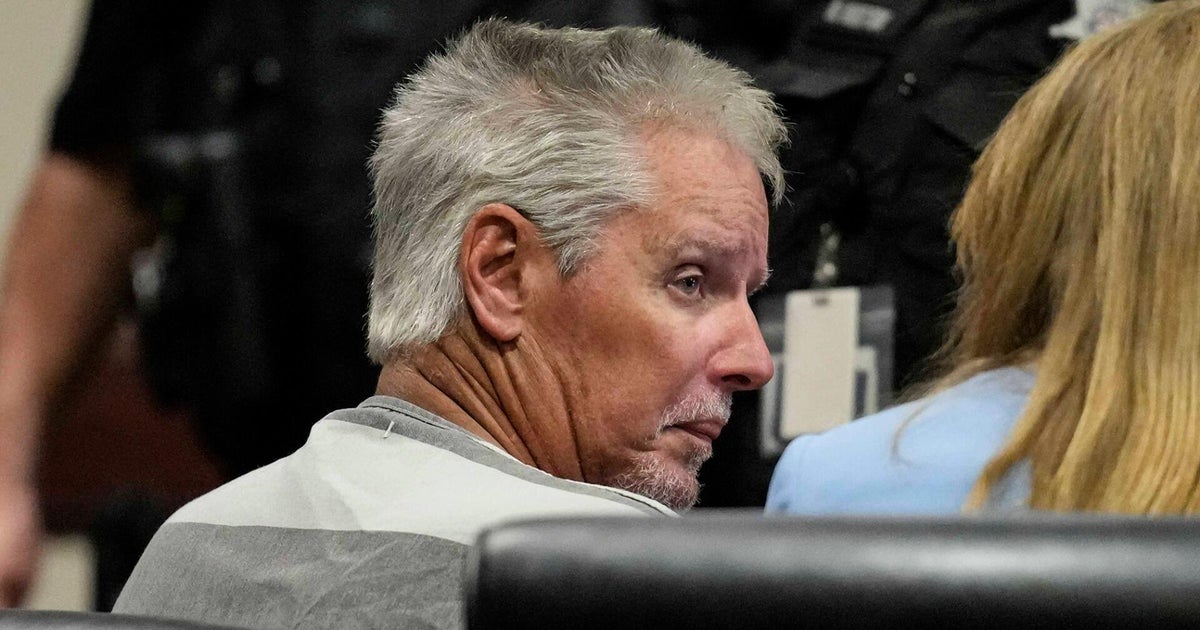

Cosby walked into the suburban Philadelphia courthouse Monday morning to begin the process of picking 12 jurors. More than 180 potential jurors were summoned to the courthouse Monday; 120 of them will make up the initial panel of 12 jurors and six alternates, reports CBS Philadelphia.

Last Thursday, the judge rejected demands from the comedian's defense lawyers that he step aside because his wife is a social worker and advocate for assault victims. The 80-year-old Cosby faces charges that he drugged and molested former Temple University athletics administrator Andrea Constand at his home in 2004.

The trial is slated to start April 9, assuming the jury is seated. Defense attorneys have said jurors should be told to prepare for a trial that lasts one month, and the panel will be sequestered, the station reports.

In the first trial, jury selection was moved to Pittsburgh over defense fears that widespread publicity could make it difficult to find unbiased jurors in the Philadelphia area. Cosby has a retooled legal team, led by former Michael Jackson lawyer Tom Mesereau, which didn't seek such measures this time and the jury will come from Montgomery County.

The prosecution wants to use a 2005 deposition given by Cosby in which he admitted to using quaaludes on women. Meanwhile, the defense is once again fighting to include testimony given by Marguerite Jackson, a former coworker of Constand. Constand allegedly told Jackson that she could accuse a celebrity of sexual assault for money.

A juror who spoke to The Associated Press on condition of anonymity said he was suspicious of Constand's story, questioning why she waited to tell authorities about the alleged assault and suggesting the clothing she wore to Cosby's house had influenced his view of their encounter.

Last year's case was mostly he-said-she-said, but the judge agreed last month to let the jury at the retrial hear from an additional five women who have accused Cosby, giving prosecutors a chance to portray the man once known as "America's Dad" as a serial predator.

"It's going to be much more difficult for the defense to chip away at all six, especially if there is a common thread and story," Gomez said. "That shows a pattern of behavior."

Typically prosecutors and defense attorneys can take what happened at the first trial, learn from it and improve on it in the retrial, but some experts say the climate surrounding sexual assault has changed so thoroughly that both sides should go back to the drawing board.

"There is no question that this is a very difficult time to try someone who has been accused of sexual assault," said defense attorney and Harvard Law School professor Alan Dershowitz. "For some jurors the whole movement will be on trial, because Cosby has been the poster person for this kind of accusation."

At a hearing last month, Cosby lawyer Becky James argued it would be difficult to find an impartial jury in this climate: "There's no way we will get a jury that hasn't heard these allegations against not just Mr. Cosby but many other celebrities." But Judge Steven O'Neill scoffed at the notion Cosby cannot get a fair trial.

Jury experts said the key is getting potential jurors to open up about their personal experiences surrounding sexual assault and misconduct, something that might be better done behind closed doors, in the judge's chambers, where people might be more likely to speak candidly.

"Without getting it out in the open, it can be underneath the surface," Gabriel said. "The hidden bias is always the most dangerous bias."

Philip K. Anthony, CEO of trial consultant firm DecisionQuest, said he has found jurors often don't know as much about newsy topics like the #MeToo movement as lawyers might anticipate. He also said he has found jurors want to do the right thing.

"In a case with a lot of notoriety, jurors work even harder to reach a fair and impartial decision," he said.

Last year, after more than 52 hours of jury deliberations over six days, the judge declared a mistrial. One juror said the panel was split 10-2 in favor of conviction, while another said the group of seven men and five women was more evenly divided.