Americans pay billions in "junk fees" every year. Here are some of the worst.

Lauren Wolfe said she first noticed "resort fees" in 2016 during a vacation in Key West, Florida. She'd paid $400 a night for a hotel room during the peak season, but was stunned when the hotel declined to hand over her room key unless she paid an extra $20 a day to cover a resort fee.

"It's just a cash grab by the hotel," said Wolfe, a lawyer who was spurred by her experience to start a site called Kill Resort Fees aimed at alerting consumers about the hidden charge and helping them take action. She's also the counsel for Travelers United, an advocacy group for travelers.

In her view, consumers are misled by the fees because they aren't typically disclosed when they book a room. It's difficult to determine the true cost of lodging when all the fees aren't presented up front, she noted.

"It's a way to deceive consumers," said Wolfe, 38, who lives in Washington, D.C. "Anyone who believes in a free market should support the removal of these junk fees."

Government crackdown

Federal regulators are increasingly agreeing with Wolfe's point of view, with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau recently announcing it will examine "junk fees" and potentially take steps to rein them in. The CFPB, which was created in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis to protect consumers from financial abuse, said consumers pay at least $29 billion annually in what it describes as excessive charges.

The agency singled out resort fees as well as a host of other charges, such as bank overdraft and non-sufficient funds fees, that it says are unfair to consumers. The problem, consumer advocates say, is that such fees often aren't clear to consumers, lack competition that can lower them or even eliminate them, and can drive up the cost of services far beyond what people expected to pay.

"Service charges inflate ticket prices, resort fees hike our costs to stay in hotels, and our phone bills are often laden with mystery charges," CFPB Director Rohit Chopra said in a conference call with reporters.

The bureau is asking consumers to send the agency comments before March 31 about junk fees they have encountered. (Consumers can email their comments to FederalRegisterComments@cfpb.gov or on the website www.regulations.gov; the email subject line must include "Docket No. CFPB 2022-00.")

Meanwhile, the banking industry is pushing back against the CFBP's efforts against fees, calling it "misguided."

The consumer agency's campaign "paints a distorted and misleading picture of our country's highly competitive financial services marketplace," the American Bankers Association, a trade group, and several other banking groups said in an emailed statement. "Multiple federal laws and the CFPB's own rules already require banks, credit unions and other providers of consumer financial services to disclose terms and fees in a clear and conspicuous manner, and our members do so each and every day."

After it receives comments from consumers, the bureau said it plans to use a combination of rule-making, enforcement and supervision to rein in companies from charging these types of fees to consumers.

What is a "junk fee"?

Junk fees aren't just any charge that a consumer disagrees with. Rather, they are fees that "far exceed the marginal cost of the service they purport to cover," according to the CFPB. In the agency's view, this signals that the corporation is taking advantage of a "captive audience." They also can be fees that are voluntary in name, but which consumers in the moment find it hard to avoid or negotiate.

The CFPB signaled that it plans to particularly scrutinize banking fees, which can take a financial toll on people who are caught unawares.

But some financial experts say that it is easier than ever to avoid many of these fees, such as overdraft fees, which can stick consumers with a $30 or $35 charge per occurance.

"We have these things in our pockets, really computers in our pockets, where you can check your bank's app to find out your account balance," Greg McBride, chief financial analyst at Bankrate.com, said of smartphones. "You can set up a link between your savings and checking accounts so if you do slip up, you cover that shortfall, not the bank."

Banks have relied on these fees as a way to support free checking accounts, which are increasingly offered by banks, Bankrate.com found. About half of non-interest checking accounts are free, the highest level since 2010, it found in a recent survey.

But complaints are already flooding into the CFPB, and many of them single out bank overdraft fees as a problem — and say they're not all that easy to avoid.

Below are some of the worst fees singled out by financial and consumer experts, as well as complaints already filed by consumers with the CFPB.

Resort fees

These fees can cost almost as much as the room itself, ballooning the price of a trip far beyond what a consumer expects. These mandatory fees are described as covering everything from pools to gyms — exactly the amenities that most travelers would expect their room fee to cover.

For instance, an Expedia search finds the MGM Grand Hotel & Casino is offering a room for $49 a night in February. But that will also include a $44 resort fee, bringing the total cost (with taxes) to $100 a night.

These fees are most common in tourist-heavy cities such as Las Vegas and New York, Wolfe said. But it's not only big hotels or hospitality chains that levy these fees: Airbnb allows its hosts to tack on a resort fee if they manage at least six properties.

Resort fees have sparked lawsuits and settlements, with the Pennsylvania Attorney General in November announcing an agreement with Marriott about the hotel chain's disclosure of resort fees. Marriott must now disclose the total cost of a hotel stay — including resort fees — on the first page of its booking website. However, Marriott has nine months to implement this, which means the change may not be completed until August.

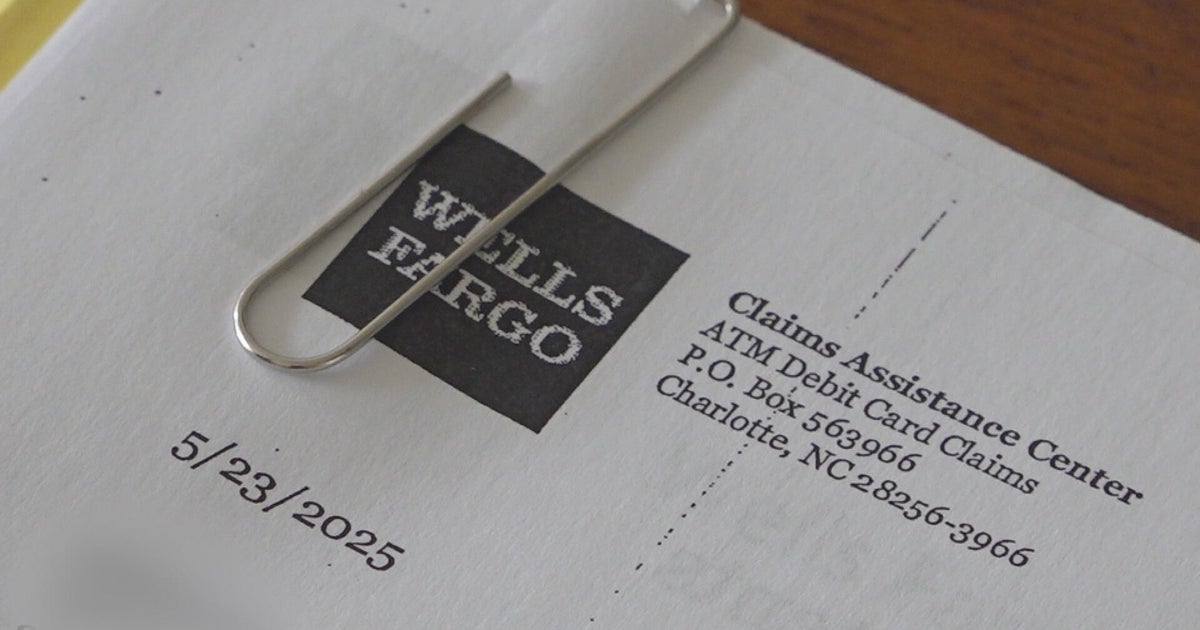

Overdraft fees

The CFPB said that Americans pay more than $15 billion annually on bank account overdraft fees, which typically cost between $30 to $35. Banks earn about $1 billion from account maintenance fees each year, the bureau said.

The agency calls these "back-end penalty fees," fobbed on consumers who don't have enough in their accounts to cover a transaction. The CFPB also points out that there's very little variation in what banks charge in overdraft fees, meaning that there is "effectively no price competition" among major banks.

Some banks have said they are cutting or eliminating the fees amid scrutiny from the CFPB and consumer advocates. Bank of America, for one, in May will cut its overdraft fee to $10 from $35.

Overdraft fees are a sore spot among the consumers who are sending in complaints to the CFPB, according to a review of recent comments posted at the Federal Register. Some consumers described ending up in "desperate" financial straights due to the fees, with small overdraft fees of a few dollars snowballing into a deficit many times greater due to these fees.

Overdraft protection fees

Say you want to avoid getting socked by a $35 overdraft fee and your bank offers you something called "overdraft protection." It may sound like a good idea, since the bank will link your checking account to another of your accounts, such as your savings, to transfer money if your checking account gets overdrawn.

The cost? About $10 to $12 per transfer, said Simon Zhen, chief research analyst at MyBankTracker.com. But consider what is actually happening, he added: Consumers are paying a substantial fee to transfer their own money between accounts.

"We have free, instant person-to-person payments, from Zelle to Venmo, and a quick little transfer of my money is going to cost me $10 to $12?" Zhen said. "It feels egregious."

Fees to pay your bills

These are often called "convenience fees" and can include fees for handling basic transactions, such as payment transfers and online or telephone payments, according to the CFPB.

The agency also counts foreign transaction fees among this group, which can add 1% to 3% of the cost of buying an item outside the U.S.

Mortgage fees

Buying a house is one of a consumer's biggest financial transactions, and the costs can rise with a plethora of fees that may not be expected by the homebuyer. These can include fees rolled into the mortgage at closing, but also ongoing charges once a consumer owns a home — such as paying fees for making home payments over the phone or online, the CFPB said.

Homeowners who end up behind on their monthly mortgage payments can also face the snowballing impact of fees, such as monthly property inspection fees and broker price opinions, the agency noted.

Ticket fees

Ticketing companies have faced lawsuits from concert- and theater-goers over their fees over the years. For instance, Ticketmaster in 2014 agreed to give credit to 50 million customers who were charged "order processing fees" and "UPS delivery fees" that weren't entirely earmarked for those purposes, according to the Wall Street Journal.

One consumer alerted the CFPB to a fee that he felt was "ridiculous." He noted that if something happens and you can't attend an event and want to resell your ticket, the ticketing company charges a fee for that — and also charges the person buying the ticket a fee.

"How is it legal for them to charge 3 sets of fees on the same set of tickets?" the consumer asked the CFPB.