Ex-British spy on leading a "double life" as a famous author

The name David Cornwell is probably unfamiliar to most of you, but he's an interesting person to talk to in these days of alleged political conspiracies, espionage, and a rekindling of the Cold War. He is an expert on secrets, a former spy himself, and the author of two dozen books, virtually all of them best sellers written under the pen name John le Carré.

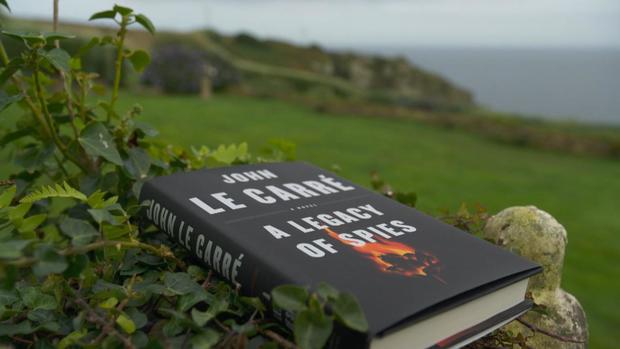

Among them are The Spy who Came in from the Cold, The Little Drummer Girl, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, The Constant Gardner and The Night Manager, all of which have been made into films. He is not just a popular writer of thrillers, he is a novelist of some standing, often compared to Graham Greene, Joseph Conrad, and Somerset Maugham. Cornwell has been living this double life for more than fifty years now and rarely gives television interviews, but last September, upon the publication of his 24th novel, "A Legacy of Spies," we were invited to spend a few days with this Literary Lion in Winter.

"Each book feels like my last book. And then I think, like a dedicated alcoholic, that one more won't do me any harm."

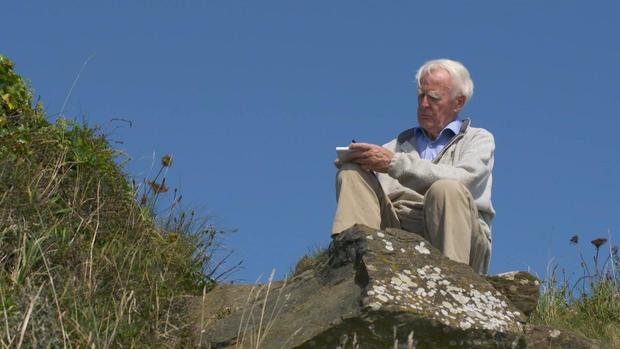

To find his natural habitat, you must journey six hours from London, through farmland and down one-lane country roads lined with hedgerow and Blackthorn, to a corner of England so remote it's known as Land's End. Here, nestled on a cliff in Cornwall, you will find John le Carré's safehouse.

STEVE KROFT: So this is where you escape to?

JOHN LE CARRÉ: Yeah. It was as far from London as I could get reasonably.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: I guess the other thing to say about this place, which is very important to me, is that the Cornish don't give a damn for celebrity. If they even know what I do they haven't read it. Or if they have read it, they make a point of not being impressed by it. And that is enormously soothing. Not a head turns in the street when I walk by.

It's here, in the home he fashioned out of three derelict cottages more than 40 years ago, that he weaves together the threads of memory, experience and research into his tales of intrigue. The solitude is his stimulation.

"It's a very close bond. George Smiley is my secret sharer, my companion. And I think that, because I'm given to exaggerated emotions at times, Smiley moderates me as a writer."

STEVE KROFT: You said many times that you don't like giving interviews.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: Yeah, I think that's true. And then I defect from that position.

STEVE KROFT: It's very clear that almost every interview you've given over the last 10 years, you've told them that it--

JOHN LE CARRÉ: It was the last one.

STEVE KROFT: This was going-- the last one.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: It always is.

STEVE KROFT: Well, I take the fact that you're still giving interviews that you're aging better than you thought you would.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: I think that's perfectly true. Each book feels like my last book. And then I think, like a dedicated alcoholic, that one more won't do me any harm.

David Cornwell's not a functioning alcoholic but he's created a stable full of imperfect characters over the years as John le Carré, a name he does not answer to. It's an abstraction that exists in his writing studio, and on the cover of his books, like a spy's name on a phony passport.

STEVE KROFT: John le Carré is sort of a cover.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: It's a separate identity in a way. And you can look after it. And looking after le Carré and keeping myself young, keeping the child in me alive-- keeping a critical nature of life whizzing in my head, that's being le Carré.

STEVE KROFT: Is there any space between David and John?

JOHN LE CARRÉ: Yes, I think a lot really. David tries to be a good dad and a regular guy with difficulty, many flaws. And John takes off into the ether. He's the man of imagination. And I can take John for a walk, let him loose on the cliffs. And he has a good time and he populates the empty cliffs with the people of his imagination. And then I come back and help with the washing up.

Le Carré was created by Cornwell in 1961, out of necessity not choice. It happened during his first career as a spy for British intelligence, both at home and abroad. To satisfy a creative urge, he began writing fiction on his commute to work and during lunchtime.

STEVE KROFT: Why did you need a pen name?

JOHN LE CARRÉ: Ah, well a hard, practical reason. I was still in secret harness as you might say. I wrote my first three books from inside the intelligence world. The books had to be approved by my masters and were. But a condition was I had to choose a pen name. So I went to my publisher.

His publisher preferred short and snappy. Cornwell wanted something interesting, mysterious and French.

JOHN LE CARRÉ : I've told many lies about how it came about. Because I truly don't clearly remember. But I think I wanted, architecturally, a name in three in three parts. And I thought the acute accent at the end, these were eye-catching things. So instead of trying to look like everybody else, I tried to look a bit different as a name. And-- then somebody who is Carré as a gentleman is not quite a gentleman. That suits me fine.

That attitude doesn't just suit Cornwell it actually defines him. He has the wealth, the education and the bearing of a polished patrician but he'll never be part of the English upper class, which he abhors, plus he has the pedigree of a rogue.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: I mean, you must realize that I'm an upstart. I do come originally from a working class family. I went kind of from working class to middle class to criminal class, which was finally my father's condition. And I had to invent myself as a gentleman, a pseudo-gentleman. So it's a good American story of self-invention.

He was five years old years when his mother Olive deserted the family, leaving him and his older brother, Tony, under the chaotic charge of their father Ronnie, a colorful, charismatic conman and crook.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: If there remains one great conundrum in my life, it is my father-- who seems to me to-- to inspire also some of the worst or best characters in me. He had a wonderful brain. Everybody who worked for him was in awe of his intellect. But if there was a bent way of doing something, he took it.

STEVE KROFT: A rich vein of material for you to mine.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: Wonderful. Wonderful, rich vein of material. And very painful.

Ronnie ran with a fast crowd, celebrities, sportsmen, and mobsters. There were racehorses at Ascot and trips to San Moritz. They lived either as millionaires or paupers, one week a chauffeured Bentley, the next on the run from bill collectors or worse.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: He'd done quite a lot of jail. And he spent some years of his life on the run in late middle age. So it was a mess, just a bloody mess. But that-- surviving it -- it was also a privilege to be part of it in some strange way. It taught you a lot about life, lowered your expectations, raised them in other ways.

STEVE KROFT: What did you learn?

JOHN LE CARRÉ: I learned, I think, to understand the wideness, the width of the spectrum of human behavior. And—I guess I learned the perils of charm, which he exercised ruthlessly with huge success. And I learned about the insecurity of the world. That everything is transient, even our money, our future, our lives, our children, everything.

He was always an excellent student, and by the time he graduated from Oxford with a degree in Modern Languages, he'd already learned from his father some of the prerequisites of a career in espionage -- lying, manipulation and deception. When he was approached by a recruiter for the British Secret Service, it seemed like a seamless transition.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: When it comes to recruiting people for the secret world, what the recruiters are looking for is pretty much what I had. I was unanchored, looking for an institution to look after me. I had a bit of larceny. I understood larceny. I understood the natural criminality in people-- because it was-- it was all around me. And I have no doubt there was a chunk of it inside me too. Once I found that identity, it took root in me. It exactly – it gelled with the world that I'd known in the past.

He began in London, running agents, keeping tabs on subversives and spies, and learning the tradecraft. He moved to the foreign branch, MI-6, at the height of the Cold War, posing as a young diplomat at the British Embassy in West Germany, just as the Berlin Wall was going up.

STEVE KROFT: What were you doing when you were working for MI6?

JOHN LE CARRÉ: In Germany, I never talk about that.

STEVE KROFT: You can't.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: No. I would never be comfortable talking about it. And I think you find that with most people who've been in that world. It is simply anathema.

Whatever David Cornwell's duties were, John le Carré found time to write a novel about a washed-up spy named Alec Leamas, who is sent on a dangerous mission across the Wall and betrayed by his bosses.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: My memory is that I wrote it very fast, the story. But I had no idea where I was going at first. And it just flowed. And I think you get a break like that once in your writing life. I really believe-- nothing else came to me so naturally, so fast.

STEVE KROFT: You had to show it to--

JOHN LE CARRÉ: I then showed it to--

STEVE KROFT: the service.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: My department. And there was a bit of a loud silence. And then actually, as was a kind of sporting decency almost, my service said, "OK, go ahead and publish it." But I think they had no idea, any more than I did, that it would become a sensation.

"The Spy Who Came in from the Cold" was the publishing event of 1963. The book spent 34 weeks as No. 1 on the bestseller list and was made into an acclaimed motion picture starring Richard Burton and Claire Bloom. Both the novel and the film served as grey, gritty antidotes to the fantastical world of James Bond, and were accepted by critics and the public as an authentic portrayal of the scruffy business of espionage.

Alec Leamus: What the hell do you think spies are? Moral philosophers measuring everything they do against the word of God or Karl Marx? They're not. They're just a bunch of seedy, squalid bastards like me. Little men, drunkards, queers, henpecked husbands, civil servants playing cowboys and Indians to brighten their rotten little lives. Do you think they sit like monks in a cell balancing right against wrong?

The book would make John le Carré, a famous and much in-demand author, but for months only British intelligence knew who and where he was and it did not want to blow Cornwell's cover in Germany.

STEVE KROFT: People didn't know it was you.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: No, they didn't, until the Sunday Times blew the whistle. And then-- the whole investigation of my person, as you might say, came up. Was I a spook? Was I not a spook? And I, out of loyalty to my service and out of some sense of privacy, went on insisting that I'd had no intelligence experience, until it became absurd. And it became absurd largely-

STEVE KROFT: I did--

JOHN LE CARRÉ: Largely with my colleagues and my superior officers were either boasting or complaining to anybody who would listen that I'd written the book.

Spooks are generally wary of unscripted publicity, so he and the agency eventually agreed to part ways allowing him, and le Carré, to concentrate full time on fiction, not unlike his father Ronnie.

STEVE KROFT: You have mused on at least one occasion about whether there's much of a difference between what you do for a living and what he did.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: Well, I think that's kind of me.

STEVE KROFT: What were you talking about specifically?

JOHN LE CARRÉ: Well, I was saying that I live off my wits, as he did. I look around, I collect bits of people. I assemble them. I pitch a story. I sell it. He, as a conman, does much the same. I do it on the page. And he does it with human material. But what that doesn't take account of is what happens to the human material.

STEVE KROFT: You've said, and I don't know what the context was-- but I've seen this quoted a number of times. You said, "I'm a liar, born to lying, bred to it, trained to it by an industry that lies for a living."

JOHN LE CARRÉ: Yeah. All of that's true. Actually, it's a dreadful confession. But these days, I tell the truth.

For the most part, the novels of David Cornwell, written under the name John le Carré, are about spies and espionage. That's the subject matter anyway and the setting, but they're also about human nature and behavior; about honor, ambition, careerism and conflicting loyalties that could apply to any profession. It's a way of writing large about the small world of secret intelligence services that Cornwell was part of, and not a bad way, he says, to take measure of a nation's political health.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: You feel that you've got a hand somehow on the subconscious of the nation. You feel you know what the greatest anxieties are and the greatest ambitions are.

In le Carré's world, the headquarters of the British intelligence services existed some years ago in an imaginary building off the theatre district in Central London.

Soundup: London Station Couldn't be in better hands!

As portrayed in his books and the movies about them, this den of spies was a drab bureaucracy populated by eccentric characters working in a long-neglected Victorian pile of bricks called the Circus.

Soundup: About time someone oiled this thing, isn't it?

We keep asking!

It was not exactly an accurate description of the real thing, Cornwell says, but it was credible.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: It was an abstraction from reality.

STEVE KROFT: Was it known as "the Circus" to the people who were—

JOHN LE CARRÉ: No, no, no. It wasn't.

STEVE KROFT: That comes from your imagination?

JOHN LE CARRÉ: I lifted the building, body and soul, as you might say, replanted it in Cambridge Circus -- different part of London, and it was known by the shorthand as "The Circus." And what better name for a community of performing-- performing spies than the Circus.

There were scalp hunters, lamplighters, honey traps and moles.

STEVE KROFT: All of this came from your imagination?

JOHN LE CARRÉ: Yes. I mean, something always sparks the imagination, and mine was sparked and took off, and I thought, "This is a kind of half-dream world which I can inform from experience." And it fits.

STEVE KROFT: People who work there recognize it?

JOHN LE CARRÉ: It isn't as if they recognize this operation or that operation. What they recognize is the smell, and the authenticity of, I hope, of the life that we led.

John le Carré: Secret service headquarters was down on the righthand side.

In London, Cornwell took us on a cab ride to see the actual building where he worked…and that used to house MI6 headquarters.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: And it was dusty and smelly and it smelled of, sort of, Nescafe and fags. People smoked. Everybody seemed to smoke. Lot of alcohol. A lot of alcohol.

It's now an office building not far from Buckingham Palace.

STEVE KROFT: There much security--

JOHN LE CARRÉ: There was no security at all. I mean, none. None that was visible. You walked in and out once you were a familiar face. And it was, "Good morning, Mr. Cornwell." Good morning this. Hallo Bill. And when you came back from abroad it was always, "Welcome back, Sir."

STEVE KROFT: But nobody searched the bags going in and out?

JOHN LE CARRÉ: No. I-- I d-- I never knew of anyone being stopped and searched.

There would be a price paid for the complacency, when MI6's most notorious double agent, the Cambridge-educated spy Kim Philby, waltzed out the door with some of Britain's most valuable secrets and handed them over to the Soviet Union.

The incident was an inspiration for Cornwell's most memorable success, "Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy." The book and this BBC adaptation are about the search for a Russian mole at the highest level of the Circus…

Soundup: We have a rotten apple, and the maggots are eating at the Circus.

Conducted by le Carré's portly spymaster and favorite character, George Smiley.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: It's a very close bond. George Smiley is my secret sharer, my companion. And I think that, because I'm given to exaggerated emotions at times, Smiley moderates me as a writer.

The character played by Alec Guinness in this BBC version, is about as close as le Carré gets to a hero. At best middle-aged, a hapless cuckold…he is measured, sensible, clever and devoted to his job.

STEVE KROFT: What do you like best about Smiley?

JOHN LE CARRÉ: I think how he toughs it out.

STEVE KROFT: Survivor.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: More than that. He does a good job.

Soundup: Tidy up!

JOHN LE CARRÉ: And much of it is distasteful to him. But he has a sense of duty. And he has a sense of moral obligation and a sense of balance.

Soundup: George… you won!

JOHN LE CARRÉ: He's made a lot of compromises with life.

Soundup: Did I? Yes, yes I suppose I did.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: And it's actually his greatest operational weapon is his humanity.

It been nearly 30 years since Smiley and his old Circus performers have appeared in a le Carré novel, but some of them are back for the new one: "A Legacy of Spies"... and unceremoniously called to account at the gleaming new MI6 headquarters, for the sins, failures and betrayals committed decades earlier in "The Spy Who Came in from the Cold."

STEVE KROFT: This struck me as something you've been wanting to do for a while.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: Well it is. In the first place, the characters never left me. In some curious way, particularly Smiley, they became -- even if I wasn't writing about them -- they became quite conscious companions at times in my imagination. And what I wanted to do at this stage, this point of closure in the Smiley saga now 50, 60 years on, was have the present interrogate the past about what we did then in the Cold War in the name of freedom. And was it worth it. And it was with this very mood very much that I concluded the book and the search for George Smiley, which for me was some kind of search for truth.

What he loves best about writing is the privacy of it. Every day sometime, after 7 a.m., he climbs the steps to his studio and begins putting pen to paper.

Soundup: And this is my workroom.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: If there are family crises and things like that, I edit them out until midday.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: This is from "Legacy." And this is Peter Guillam, the central figure, who is narrating. I have two visions simultaneously. The first, of George, that's George Smiley. And Alec, that's Alec Leamas. Huddled head-to-head in the chilly conservatory. In Bywater Street. Rare use of an adjective by me.

Most of the material comes from notebooks he's filled on long walks or epic research trips he's taken to capture the feel and smell of faraway place he puts his characters.

Soundup: This is all the very raw material.

These notes were jotted down in Kenya while he was writing "The Constant Gardner."

JOHN LE CARRÉ: These are things I saw. Batons, a Panga from somewhere. "The man lies in the recovery pose, bathed in blood from the head down, dead or going there. In Nairobi, murder is one of the few industries that that live up to expectation."

There are no computers involved in this process. He edits with scissors and a stapler.

Soundup: And that's the extract.

And hands the good bits off to his personal typist and copy editor, Jane Cornwell, his wife of 45 years. She is also Chief Operating Officer of his life and various enterprises.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: Like all writers. I've lived a messy, untidy life, inevitably so, and she's been wonderfully supportive. And it's always go to Jane if you need to get to David, 'cause she's got her feet on the ground. God knows where he's got his feet.

Cornwell has been writing as John le Carré for so long, no one could tell us how many millions of books he's sold over the last five and a half decades…they've been printed in 43 different languages.

STEVE KROFT: How do you think of yourself as a writer?

JOHN LE CARRÉ: Wow. Storyteller. So we're sitting in front of a fire. I want to keep you in your chair. I want to interest you. I want you to want to turn the page. But I don't really think too much about the posterity. And I certainly don't join the literary argument about where I stand. Am I a quality novelist? Am I a popular novelist? Am I a thriller writer? To me, if I'd gone to sea I'd have written about the sea. If I'd gone into stock broking, I'd have written about the stock broking world.

STEVE KROFT: You've turned down literary honors. You've turned down a knighthood.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: Yes.

STEVE KROFT: Why?

JOHN LE CARRÉ: In my own country, I'm so suspicious of the literary world that I don't want its accolades. And least of all do I want to be called a Commander of the British Empire or any other thing of the British Empire. I find it emetic.

STEVE KROFT: And why do you feel that way?

JOHN LE CARRÉ: I don't want to posture as somebody who's been honored by the state and must therefore somehow conform with the state. And I don't want to wear the armor.

STEVE KROFT: Your writing partner, George Smiley, had this to say on the subject. "The privately educated Englishman is the greatest dissembler on Earth. No one will charm you so glibly, disguise his feelings from you better, cover his tracks more skillfully, or find it harder to confess that he's been a damned fool. No one acts braver when he's frightened stiff or happier when he's miserable. And nobody can flatter you better when he hates you than an extrovert Englishman or woman."

JOHN LE CARRÉ: Yeah. I think that's very good.

STEVE KROFT: You like that graph.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: I like that, yes I do.

STEVE KROFT: Do you consider yourself an Englishman?

JOHN LE CARRÉ: What kind of Englishman at the moment? Yes, of course, I'm born and bred English. I'm English to the core. My England would be the one that recognizes its place in the European Union. That jingoistic England that is trying to march us out of the EU, that is an England I don't want to know.

Like most Europeans, Cornwell has no use for President Donald Trump and his nationalistic agenda, which he calls alarming and contagious and he worries about the ambitions of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

JOHN LE CARRÉ: I think today's spooks working on the Russian front-- British spooks, would tell you that it's just as bad as it was in the Cold War. Putin sees everything in terms of conspiracy, and his grip on the Russian populace is so strong that he has resorted to all the old systems that he was familiar with. So, we're right back to where we were in the Cold War, with the added mission that Putin has given to himself to erode decent democracy wherever he sees it.

STEVE KROFT: So much has changed the world of espionage since you first began. I mean, you have the introduction now of cyber war. You have computer hacking. You have all of this stuff. You--

JOHN LE CARRÉ: Yeah--

STEVE KROFT: You wonder, is it possible that-- to keep any secrets at all? And do we need spies? Any human spies?

JOHN LE CARRÉ: I think probably in many ways, more than ever. In some ways, the techniques of intelligence and the techniques of maintaining secrets have gone backwards. If you and I are gonna enter into a conspiracy now, we don't do it through the ether. We don't do it by computer. We exchange notes. We either hand each other notes-- we keep paper again. Paper is back in. Secondly, you very, very often need an agent on the spot who is going to deliver the piece of paper, the code number, the simple clue to it all.

Mostly right now, David Cornwell and John le Carré are recovering from, celebrating and lamenting publication of this last novel. Strange as that may seem.

STEVE KROFT: You said the most depressing time in your life is when you finished a book?

JOHN LE CARRÉ: Yes. Yes.

STEVE KROFT: Which is what you're going through right now?

JOHN LE CARRÉ: Which is exactly what I'm going through right now. Thank you for lightening my load. Yeah, it's a feeling of-- you've depleted everything you've been working on. It's done. It's out there. And then out of the ashes of the last book, so to speak, comes the phoenix of the new one, and then life's OK again. But the depression that overtakes me when I've turned in a book, I must confess is real and deep.

STEVE KROFT: Do you have an idea for the next book?

JOHN LE CARRÉ: Absolutely. I can't wait to get to it.

Produced by Michael H. Gavshon and David M. Levine.