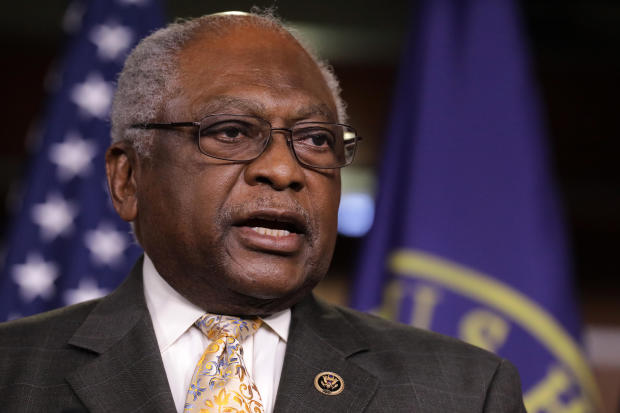

Rep. Jim Clyburn says there's a "dark place" on the horizon for voting rights

To House Majority Whip Jim Clyburn, the highest ranking Black legislator in Congress, "racial gerrymandering" — what he describes as the intentional drawing of congressional districts that discriminate against minority populations — has deep roots in America's history.

He recalled areas around his home county of Sumter County, South Carolina, voting overwhelmingly in the 1968 presidential race for pro-segregationist independent candidate George Wallace, despite its large Black population.

"Why is that? They turned racialized voting into an art form. And they used the presence of African-Americans to frighten people into what we're seeing taking place again," Clyburn told CBS News chief election and campaign correspondent Robert Costa in a recent interview.

Clyburn, a Democrat, expressed alarm over how redistricting efforts in many states this year has affected people of color. And he believes that the recent efforts can be traced back to Wallace's 1968 campaign in the South.

"It's one thing to look at the headlines, it's another thing to look behind them. And I tend to look behind the headlines," Clyburn said.

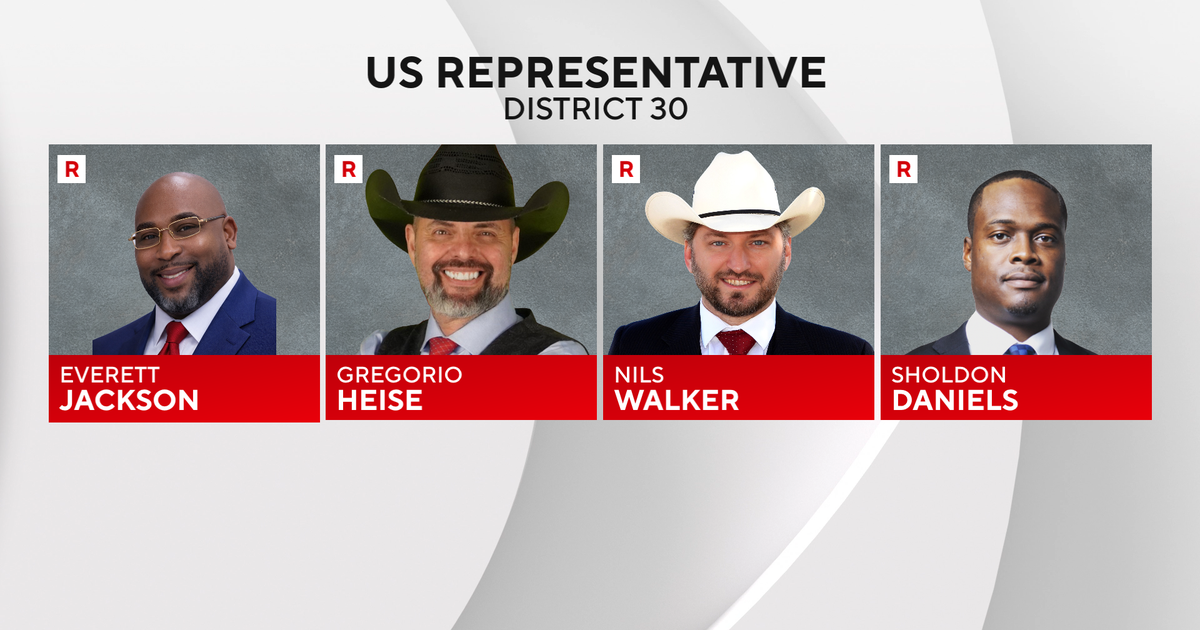

While it varies state to state, this year's redistricting resulted in a slight net-gain in the amount of Democratic leaning seats nationwide.

However, GOP legislators turned seats that have been competitive in the past decade into solidly Republican seats.

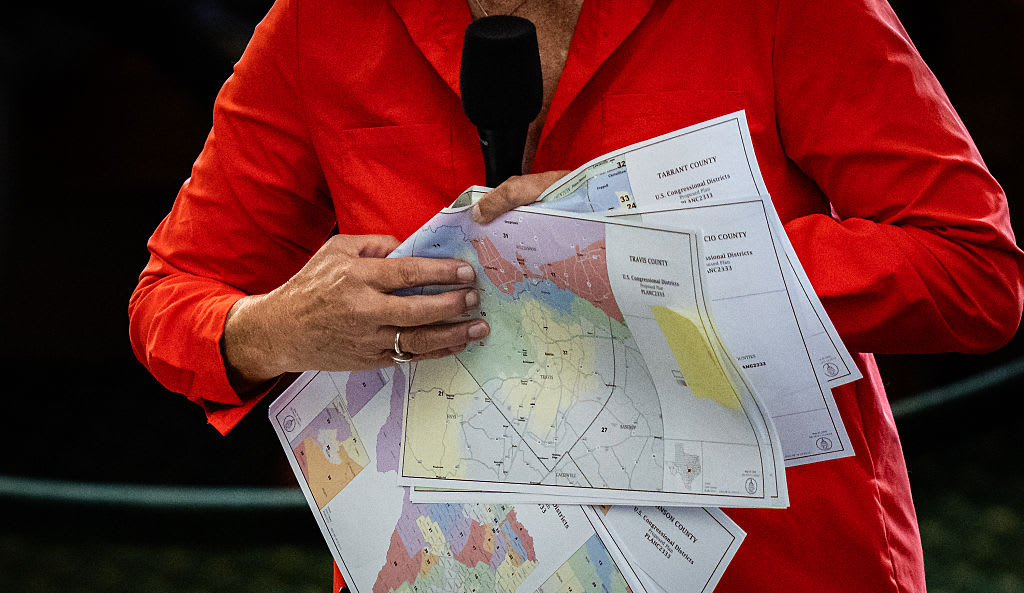

In Texas, the number of competitive seats (those that have a +/- 5 point partisan lean) decreased from 12 to two, while the number of Republican leaning seats increased by nine, according to a CBS News analysis of election data from Dave's Redistricting App.

This happened despite the growth in minority and biracial citizens, according to data from the 2020 Census.

Similarly, Georgia's population grew by more than a million in the past decade, fueled by a growth of Black, Asian and Hispanic residents near Atlanta. Yet legislators added one solid Republican seat north of Atlanta by drawing in more rural and White areas into the 6th District, and "packing" the largely Democratic and minority areas into the 7th District.

Clyburn wouldn't label such actions as "racist," but said the maps do give "racial advantage, in the guise of giving partisan advantage."

"Aggressive redistricting efforts, that's one thing. To be suppressive of Black voter strength, that's another thing," the congressman said. "Yes, Democrats look for partisan advantage. Republicans look for partisan events. I don't have a problem with either one of those parties doing that. I do have a problem when it comes to the result adversely affecting the lives of Black people."

"They're taking race into account, but not to be fair, not to be inclusive, but to do just the opposite, to be exclusive," Clyburn added.

In its next term, the Supreme Court will weigh in on whether Republican legislators in Alabama and Louisiana violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act by only having one minority-majority seat in each state.

Alabama's population is 26.8% Black, according to data from the Census Bureau, though only one-seventh of their congressional districts have a majority-Black population. Louisiana's population is 33% Black, though only one-sixth of their congressional districts have a minority-majority population.

The impacts of redistricting are already clear in several states. Georgia's 14th District, which is represented now by Republican Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, will include the predominantly Black town of Powder Springs when the new map takes effect in 2023. Greene spoke at a conference founded by white nationalists in February.

Though Greene initially criticized Georgia Republicans for slightly reducing the Republican share of the vote in the state, she told CBS News in May before her primary, "I'm excited to have them in my district and I just love Georgia."

Clyburn said he is "outraged" by how districts have been drawn, particularly those with significant Black populations.

"What has happened with some of these legislatures, they've decided that because the Supreme Court has allowed for partisan redistricting to take place, they are going to use that as a cover for redrawing districts in such a way that gives undue advantage," he said.

In South Carolina's new congressional map, Clyburn's district no longer has a majority-minority population. The percentage of Black residents in his district dropped from 53.3% to 47.82% in the newly-enacted map. There are no congressional districts in South Carolina with a majority Black population, despite the state's Black residents making up over a quarter of the total population.

There have also been accusations of racism in maps in Democratic states. In May, the initial map proposed by a court-appointed map drawer in New York was criticized by many House Democrats for reducing the number of Black members of Congress.

John Faso, a former Republican congressman from New York, had been advising Republicans in their battle with Democrats over the congressional and legislative lines. He believes "more and more voters will be looking beyond race in terms of who they're choosing to elect to office."

"Fair play is what Americans want," he said, though added that the political impact of redistricting may be "overstated" at times.

"Over the long term, if candidates and parties don't reflect the views and values of the people in their state and their district, they're going to get voted out of office," Faso said.

Clyburn said while redistricting gives House Democrats important political benefits, he looks at it more as "keeping balance." He said he supports a bipartisan policy in every state to address redistricting.

However, he suggested there's not enough of a "will" within the Democratic party to change the process.

"The reason we have not created a way to address all this, in my opinion, is that we have not developed the will to do it," Clyburn said. "Sometimes that's because people fear for their own safety, some people fear for their own security and some people would just rather have favor than freedom."

Clyburn, who was first elected to Congress in 1993, said he believes there's a "dark place" on the horizon for voting rights if racial gerrymandering is not addressed.

"What I think is taking place today is the beginning of a process, not the ending of one. And the question is, 'Where will it end?' Will it end with the intervention from the voters in 2022? Or will it get a second breath and continue until we go back to a dark place that none of us thought we would ever revisit again."

Elizabeth Campbell contributed reporting.