JFK legacy: Setting America on course for the moon

In May 1961, John F. Kennedy, a charismatic young president with bold dreams for a re-energized America, stood in the eye of a perfect geopolitical storm.

A few weeks earlier, on April 12, Russia’s Yuri Gagarin became the first human being to fly in space, a feat that generated world-wide admiration and, in some quarters, near hysterical fear that the United States had been surpassed by its Cold War rival.

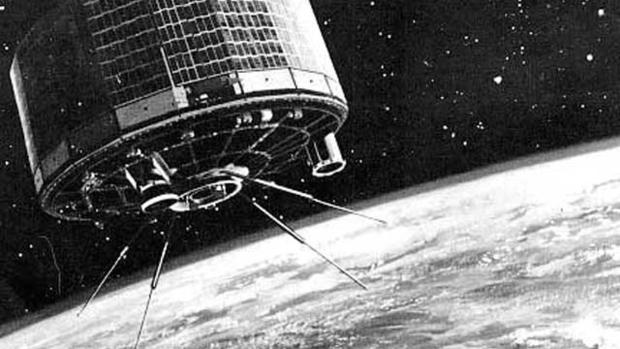

The Soviet Union had already shocked the West with the launch of Sputnik, the first artificial satellite, in 1957. Using the world's most powerful rockets for their space spectaculars, the Russian launches clearly demonstrated an alarming ability to impose the Soviet Union's nuclear will around the world.

As related by space analyst John Logsdon in his 2010 book "John F. Kennedy and the Race to the Moon," Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev told Gagarin in a congratulatory phone call, "Let the capitalist countries catch up with our country!"

As Logsdon outlines in fascinating detail, Kennedy met with his top advisors two days after Gagarin's flight to discuss the goals of America's budding space program and what steps might be taken to counter the perceived threat posed by the Soviets.

It was a decidedly pragmatic approach by a president who had expressed little previous interest in space beyond concern about the so-called "missile gap," the disparity between large Russian boosters and lower-power American rockets.

But with the advent of television and mass communications, the missile gap and subsequent space race played out in the glare of TV lights and Kennedy was quick to seize the stage.

"Kennedy fully and completely understood that whether he paid any attention to it or not, the rest of the world was paying attention to it," former NASA Administrator Mike Griffin said in an interview. "And if the rest of the world was paying attention to it, then he was, by God, not going to pull an Eisenhower, he was going to win."

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration, created by the Eisenhower administration in the wake of Sputnik, already was mapping out a variety of long-range strategies, including possible moon missions. There was no obvious support for any sort of emergency effort and Kennedy had not given the issue any serious thought.

But Gagarin's history-making flight changed all that. Lawmakers and the media, reflecting public opinion -- or, perhaps, fueling it -- demanded quick action to match and even surpass the Russians.

During the April 14 meeting with senior advisors, Logsdon said Kennedy listened to a variety of proposed initiatives, saying at the end "when we know more, I can decide whether it is worth it or not. If somebody can just tell me how to catch up. Let's find somebody -- anybody."

Three days later, the perfect storm intensified when 1,400 Cuban exiles launched what became known as the Bay of Pigs invasion on the southern coast of Cuba. President Eisenhower approved the program and Kennedy signed off on the invasion plan shortly after his inauguration.

But without sufficient U.S. air support, the CIA-trained exiles were easily overwhelmed by Fidel Castro’s army. It was a disaster for them and for American foreign policy, another black eye on the world stage.

On April 20, with the Bay of Pigs fiasco still front page news, Kennedy sent a memo to Vice President Lyndon Johnson, chairman of the National Space Council, listing five major questions and ending with a directive to report back "at the earliest possible moment."

The memo asked, "Do we have a chance of beating the Soviets by putting a laboratory in space, or by a trip around the moon, or by a rocket to land on the moon, or by a rocket to go to the moon and back with a man. Is there any other space program which promises dramatic results in which we could win?"

The memo asked how much such a program might cost and wondered, "Are we working 24 hours a day on existing programs? If not, why not? If not, will you make recommendations to me as to how work can be speeded up."

The president also asked about what sort of propulsion new U.S. rockets should use. He concluded by asking, "Are we making maximum effort? Are we achieving necessary results?"

The memo reflects Kennedy the pragmatist in no uncertain terms.

"One wants to maintain some element of Kennedy as a visionary," Logsdon said in an interview with CBS News. "But the reality of the man is that he was not really that much of a visionary. I think the vision was imposed upon him because he was young and charismatic and spoke in visionary rhetoric. But his actions weren't visionary."

Against this backdrop, NASA successfully launched its first manned space mission on May 5, 1961, sending astronaut Alan Shepard aloft on a 15-minute sub-orbital flight.

The brief mission gave the United States its first space triumph, and while the Mercury Redstone rocket was much less powerful than the Russian booster that lifted Gagarin into orbit, the success was a shot in the arm for an administration reeling from public setbacks. Shepard became an instant hero.

"You think about Alan Shepard going up and he became a folk hero, and John Glenn in February of '62 was given a ticker tape parade like nobody had seen since Charles Lindbergh in 1927," said historian Douglas Brinkley. "And so Kennedy was able to make cowboy heroes, myths, out of (the) Mercury astronauts, and led the way for Neil Armstrong's moonwalk (in) 1969."

Three days after Shepard's flight, as Logsdon relates, a 30-page report prepared by NASA Administrator James Webb and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara was presented to Johnson who, in turn, passed it on to the White House.

The report listed five primary goals for a re-vitalized U.S. space program: a manned lunar mission "before the end of the decade;" development of communications satellites and orbital weather stations; establishment of a vigorous science research program; and development of new, heavy-lift rockets. The projected cost was around $20 billion.

After mulling it over, Kennedy signed on, setting the stage for a dramatic nationally-televised speech before a joint session of Congress on May 25 to discuss "urgent national needs."

After addressing economic issues, assistance to developing nations, increased military spending and related topics, Kennedy turned his attention to space, delivering a line that will forever be remembered as the birth of the Apollo moon program.

"I believe this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth," the president said. "No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish."

By this point Congress was fully on board and on Aug. 7, a $1.67 billion budget was approved for NASA, an 89 percent increase over the previous Eisenhower administration appropriations request. The quick congressional approval was the result, Logsdon says, of Johnson's efforts to consult with leading lawmakers throughout the process as well as the near hysteria Gagarin's flight generated.

Looking back from the perspective of five decades, it seems almost beyond belief that at the time Kennedy called for a manned lunar mission "before the decade is out," the United States had launched only a single astronaut on a 15-minute sub-orbital flight.

But NASA's management was confident they could deliver on the president's promise and as the money flowed, the growing agency quickly expanded with new facilities sprouting up across the country, helping secure long-term political support with jobs across dozens of congressional districts.

Despite the early momentum, criticism slowly grew, with some questioning the enormous cost and others suggesting unmanned exploration would be cheaper and more scientifically productive.

But Logsdon shows Kennedy never lost confidence in his long-range goal. While the president repeatedly questioned the program's execution and seriously explored the possibility of joint exploration with the Soviet Union, he remained a stalwart supporter of the moon program.

"We choose to go to the moon," Kennedy said during a speech at Rice University in Houston on Sept. 12, 1962. "We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others, too.

"It is for these reasons that I regard the decision last year to shift our efforts in space from low to high gear as among the most important decisions that will be made during my incumbency in the office of the presidency."

Over the next few weeks, NASA engineers and the president's science advisor debated the architecture of the moon program, discussing the pros and cons of different scenarios for getting a spacecraft to the surface of the moon and back again.

The debate never made it to the president's desk. In October 1962, Kennedy was consumed by the Cuban missile crisis and had no time for NASA.

But he soon returned to form, Logsdon writes, monitoring the program's progress and repeatedly questioning its objectives and methodology. Up to this point, it's not clear just how much Kennedy actually understood about the inner workings of the moon program.

But during a visit to Cape Canaveral on Nov. 16, 1963, he marveled at the scale of the Vehicle Assembly Building and the launch infrastructure rising on Florida's "space coast." He was especially impressed by a huge Saturn 1 rocket being prepared for launch that December, a booster with 1.5 million pounds of thrust that finally would give America the lead in sheer launch power.

Logsdon quotes NASA Associate Administrator Robert Seamans saying Kennedy "maybe for the first time, began to realize the dimensions of these projects."

A week later, on Nov. 21, 1963, the day before an assassin's bullet cut him down in Dallas, Kennedy delivered what would be his final speech regarding the space program at the dedication of an Air Force aerospace medical center in San Antonio, Texas.

"We have a long way to go,” Kennedy said. “Many weeks and months and years of long, tedious work lie ahead. There will be setbacks and frustrations and disappointments. There will be, as there always are, pressures in this country to do less in this area as in so many others, and temptations to do something else that is perhaps easier.

"But ... this space effort must go on. The conquest of space must and will go ahead. That much we know. That much we can say with confidence and conviction."

Five and a half years later, on July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin fulfilled the president's promise, becoming the first humans to land on the moon.

At mission control in Houston, flight controllers celebrating the successful conclusion of the Apollo 11 mission put up a sign with Kennedy's famous May 25, 1961, vow to mount a manned moon mission "before this decade is out."

Below that, two words were appended: "Task accomplished."