How an Afghan family facing threats put its trust in a U.S. veteran: "You just gamble your entire life"

From his home in Kansas City — more than 7,000 miles away from Afghanistan — U.S. Army veteran Jason Kander joined with a group of private citizens to plot a fake wedding to disguise the escape of hundreds of Afghans vulnerable to the Taliban.

Many Afghan allies were left behind when American troops withdrew from Afghanistan in 2021 after 20 years of war. Kander, a one-time politician who ended his burgeoning political career to deal with untreated PTSD, collaborated with civilians and other veterans to help evacuate nearly 400 Afghans, including Rahim Rauffi and his family.

"Ultimately I just made the decision that it didn't matter. I would deal with it [PTSD] afterwards," Kander said. "And I made the decision, which I knew at the time was probably poor judgment, to say to Rahim, 'No matter how long it takes, we're going to get this done.' I knew that I was biting off more than I could chew."

What happened when the U.S. withdrew from Afghanistan

The Taliban retook Afghanistan as the U.S. withdrew. Many Afghans, fearful of what might happen under the fundamentalist Islamic group, overwhelmed the Kabul airport and clung to departing U.S. military planes in a last grasp at freedom.

"It felt like leaving a friend behind when you had promised them you wouldn't," Kander said.

At home in Kansas City, Kander watched in shock as Afghanistan fell. He reached out to Salam Raoufi, who had worked as Kander's primary translator when he served in Afghanistan as an Army intelligence officer. The translator was safe and out of Afghanistan, but his nephew — Rahim Rauffi — was not.

Rauffi was squarely in Taliban crosshairs because of his work in payroll at Afghanistan International Bank. In his job, he'd had access to a list of tens of thousands of Afghans who had worked with everybody from the United Nations to the U.S., Kander said.

"Once the Taliban took over, one of their first priorities was to find those people and make an example of them by imprisoning them or killing them," Kander said.

Rauffi's refusal to cooperate enraged the Taliban. Under the shroud of darkness, the Taliban left notes, known as night letters, at the Rauffi home sentencing Rahim and his entire family to death.

Getting Afghans to safety

Hope for a passage to safety rested in the hands of Kander — a Little League dad nine-and-a -half time zones away. He and Rauffi exchanged encrypted text messages.

"My thinking was how in the world can I go on with the rest of my life thinking, 'Maybe there was something else I could've done for Rahim,'" Kander said.

Kander's wife, Diana, became concerned her husband's desire to rescue the Rauffi family of 12 might lead him to go to Afghanistan himself.

"He called me from the other room. He's like, 'Hey — where's my passport, just by the by?' And I was like, 'Yeah, zero chance you're even getting access to your passport,'" she said.

Kander and his co-conspirators were getting desperate to come up with a workable plan.

"We were also running out of ideas by that point," Kander said.

Once the last American military plane departed Afghanistan on Aug. 30, 2021, the Taliban controlled the Kabul airport, choking off the most obvious escape route. Kander and his group directed the imperiled Afghans to head to the northern city of Mazar-e-Sharif.

The Taliban wasn't yet as entrenched in the north of the country, but for the Rauffi family the city of Mazar-e-Sharif was a treacherous 11-hour drive dotted with Taliban checkpoints. They started their journey early on Sept. 1, 2021, and were stopped almost right away by armed members of the Taliban.

"Only because of my kids' crying and shouting… they just released us," Rauffi said.

They finally rolled into Mazar-e-Sharif, Afghanistan's fourth largest city.

"The Rauffis are in Mazar-e-Sharif, and myself and the people I was now working with are engaged in solving a few problems, or trying to. One, how do we raise the money to get an airplane chartered to fly in there to pick up close to 400 people?" Kander said. "And also how do we make it so that the Taliban doesn't know that we're doing this?"

Welcome to the wedding

The day after the Rauffis arrived in Mazar-e-Sharif, the Taliban paraded in the center of town. The Rauffis went underground for weeks, finding their own safe houses. As the family dodged the Taliban, Kander and his group were finalizing a Hail Mary plan.

On Sept. 21, it was go time. Kander told the family to take one bag per person and head to a wedding palace. He gave Rauffii a code word: Bella, the name of Kander's own daughter. What Kander neglected to mention was to whom Rauffi should give the code word.

At the wedding palace, Rauffi spotted a man with a beard, a turban, a laptop and a look of authority. Rauffi went up to the man and gave him the code word and his last name.

"My heart was beating very fast," Rauffi said. "Then he said, '12 people?' I said, 'Yes.' Then he said, 'Bring them in.'"

Once inside, they headed to a large hall filled with nearly 400 people. Rauffi didn't know any of them.

"I call Jason. I say, 'Brother, I am in, but there are more people,'" Rauffi said. "Then he told me, 'Welcome to the wedding party.'"

There was no bride or groom; it was all a ruse to slip 383 Afghans past the unsuspecting Taliban.

From Afghanistan to Albania

The fake wedding threw the Taliban off the scent, but 383 Afghans were marooned in the wedding hall for three days as Kander continued developing the evacuation plan. Through crowdfunding and private donations, Kander and others frantically raised money to charter a commercial plane that would whisk away the entire "wedding party" to Albania, where they would await clearance to come to the U.S.

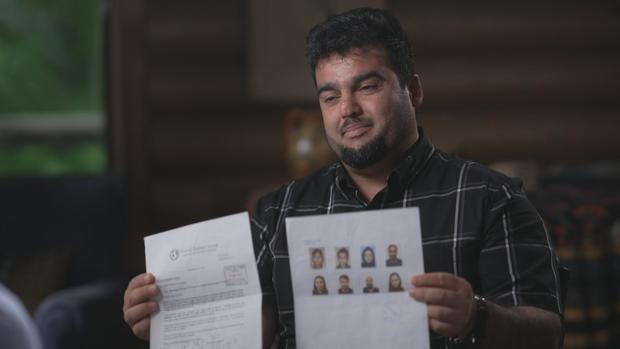

Inside the wedding hall, the Rauffis had no idea this was going on. Eventually, Rahim Rauffi got a boarding pass through email. It was on legal letterhead and didn't look particularly official. The passes were the handiwork of the rescue team in the U.S.

"The boarding passes, which were quite unofficial, only matter if there is a flight manifest document from the nation of Albania, otherwise they're just a piece of paper you're going to present and then go to prison," Kander said. "So what was going to happen was the Albanian government was going to send, to the Taliban, a visa-cleared flight manifest, a list of people that said, 'These are the people who we are expecting to have land in our country.' Now, what these people needed to do was present something that had their pictures on it, had their names, their date of birth, everything that would match up to what was on that document."

In other words, everything rested on the Taliban —a group more known for executions than following international protocol.

The 383 Afghans arrived at the Mazar-e-Sharif airport on buses. The Taliban was in the terminal and on the tarmac. Rauffi said he was shaking and sweating. The family could see their plane to freedom.

"It's a gambling that you even didn't see your cards," Rauffi said. "What you have? What you got? What will happen? But you just gamble your entire life."

The bet paid off. The Taliban honored the homemade boarding passes and the Albanian manifest.

The wedding party boarded the charter plane, while Kander —home in Kansas City— followed the drama on a flight tracking app.

"There's zero planes over Afghanistan," he said. "And then finally, they're on the plane and the transponder turns on. And you see one little airplane turn on on the runway in Mazar-e-Sharif."

After the flight landed in Tirana, Albania, the wedding party was bused to a seaside resort.

The journey wasn't over yet though.

From Albania to the U.S.

Kander still had to figure out how to get the Rauffis and the other Afghans into the U.S. He said he'd been told by people at the Department of Homeland Security that it would probably take a few weeks. But months later, Kander said the State Department announced that any Afghans who had gotten out of the country after Aug. 31 by private means would not be part of Operation Allies Welcome.

"Basically it was all code for, 'You're on your own. If you got out this way, that's a private effort, we got nothing to do with it,'" Kander said. "And that was a big shock and a huge problem."

A year passed. The wedding party was still stuck at the resort in Albania and the money covering the tab was running low.

"There were some very generous donors who helped us over time. And the people who had helped me raise the money in the first place did a lot of work," Kander said. "And it's taken a toll on all of us. But I think now if you talk to any of us, we'd say it's, you know, the most important thing we've ever done."

Finally, nearly two years into the wedding party's saga, emails arrived from the Department of Homeland Security–the Afghans had been approved officially to resettle in the U.S.

"I was, like, crying inside," Rauffi said. "Now you have a future."

He knew exactly where he wanted to call home—wherever Kander lived. In June of 2023, the Kanders welcomed the Rauffis to Kansas City.

Today, Rauffi is back to working in accounts at a bank–this one in downtown Kansas City. His brothers work there as security guards. The Rauffis and the Kanders, who now live 10 minutes apart, regularly get together for meals.

Rauffi says he sometimes wakes up during the night wondering if this is real.

"I'm going to my kids' room and see them and check them," he said. "They are sleeping very comfortable. And the next day, they are going to school."