Japan rebuilt an entire tsunami-flattened city on a man-made hill, but many still can't face life there

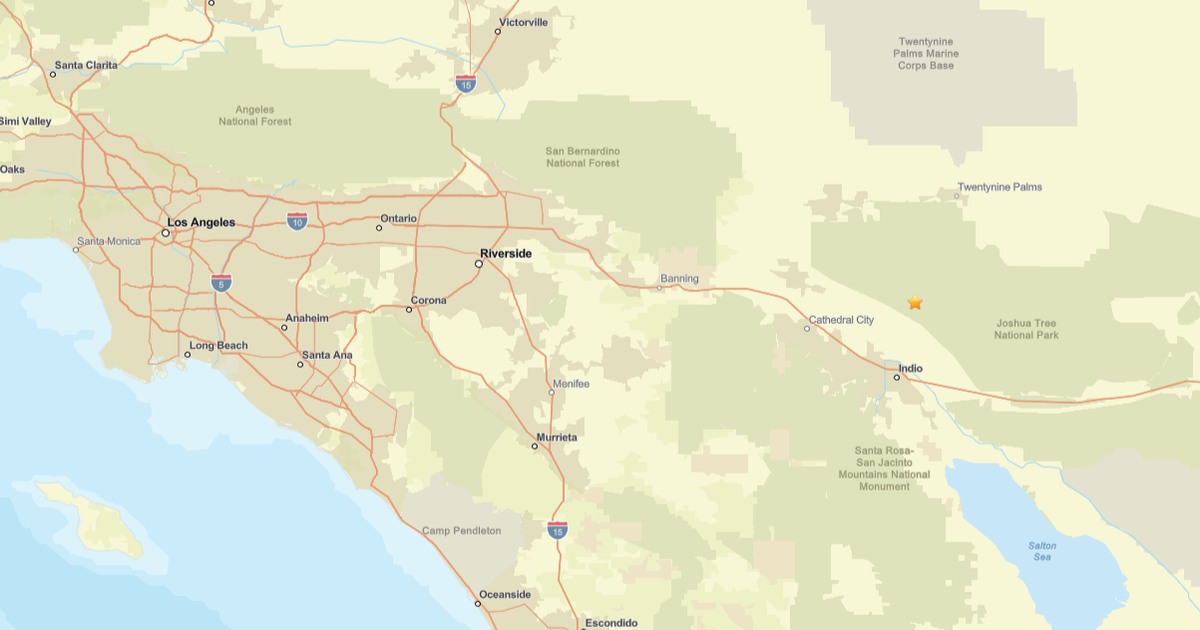

Rikuzen-Takata, Japan — Japan marked the 10th anniversary on Thursday of the devastating earthquake, tsunami and nuclear plant accident that left more than 22,000 people dead or missing along the country's northeast coast. CBS News visited Rikuzen-Takata, 300 miles north of Tokyo, and met Fumiaki Konno on the plot of land that used to be his home in the city that suffered the highest death toll per capita of anywhere in the disaster zone.

His traditional home once stood on what is now barren ground, surrounded by the houses of a large extended family. Konno's ancestors settled on the plot of land four centuries ago.

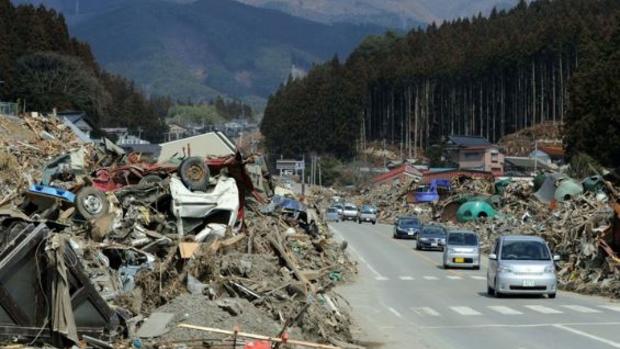

On March 11, 2011, life as he knew it was ended as the family homes were swept away by a massive tsunami unleashed by the monstrous, Magnitude-9 earthquake off Japan's coast. His entire community was washed away in just minutes.

"We lost everything. You don't count what you lost. You lost everything. It's a kind of defensive mechanism, in psychology. You try not to think about what you have lost," he told CBS News.

An austere memorial now overlooks Rikuzen-Takata's bay, where waves as high as 60 feet first crashed ashore to swallow the city.

The tsunami "came directly from there," Konno said, looking down at the bay. "Right in front of you, this open sea — you see the two peninsulas on both sides? Like two hands, welcoming the tsunami. So we are hit directly."

Today the physical scars of the tsunami have been all but erased from the city. Massive sea walls over 40 feet high have been erected, but they're just the first line of defense in what has been an elaborate effort to tsunami-proof Rikuzen-Takata.

The city literally moved mountains — using conveyor belts nearly two miles long to carry in enough gravel and rock to rebuild the Great Pyramids of Egypt — in an extraordinary civil works undertaking to lift the downtown commercial district out of harm's way.

The city that once sat at sea level has been elevated by 30 feet.

But the infrastructure bonanza, using $1 billion of Japanese taxpayers money to transform a once-sleepy provincial outpost, was a controversial project. The compact downtown now features sleek new shops, spacious recreation areas and a gleaming new baseball stadium. But all the amenities have failed to stem a steady exodus of residents from the rebuilt town.

A decade on, Konno said his city remains deeply traumatized.

"My neighbors, they are still quiet — prefer not to go back to recent memories. It's difficult to quantify, but it will be very long-lasting," he said.

Amya Miller, an American who lived in and worked for the city until 2018, said Rikuzen-Takata's enormous death toll continues to haunt survivors. More than 1,800 residents — nearly 8% of its population — died in the disaster.

"Rikuzen-Takata has the unfortunate notoriety of being the only city in the entire region where everyone in the city lost someone they knew," Miller said. "That means there's collective grief, and that is one of those things you don't snap out of it — you don't get over it. When everyone is sad together, it's intense."

In the West, particularly, many have celebrated the Japanese for their resilience in the wake of the disaster, but Miller said in her town, those sentiments feel misplaced.

"Mayor Toba will be the first one to say, what you see as resilience is actually exhaustion: We're doing this because we have to, not because we want to."

While the rest of the country is moving on from the quake, tsunami and nuclear accident of 2011, Rikuzen-Takata's residents continue to mourn, and there's no relief in sight.