Jack Ruby: The assassin's assassin

(CBS News) The name Jack Ruby is an essential part of the history of that weekend 50 years ago. For one extended family, the name is also a burden. Dean Reynolds has heard her out:

Joyce Berman remembers that day in November half a century ago when her mother unexpectedly picked her up from a friend's birthday party and took her home, with the briefest and bluntest of words:

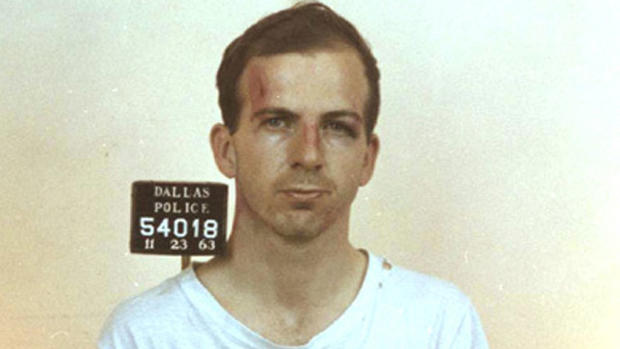

Joyce was Joyce Ruby back then, the nine-year-old niece of a Dallas nightclub owner named Jack Ruby -- the man who assassinated the assassin on network television.

"I didn't feel any different except for my last name being Ruby," she said. "And as soon as somebody knew what my last name was, they would ask me questions: 'Oh, are you related to Jack?'

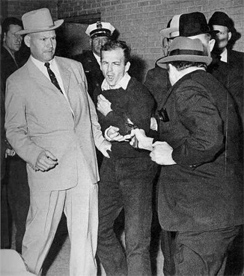

In a Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph, Bob Jackson of the Dallas Times Herald captured the moment Jack Ruby shot Lee Harvey Oswald.

"I really didn't know him. I had only met him when I was an infant, so I had no recollection of this person."The instant notoriety was bewildering and frightening to this child in the Detroit suburbs.

"I remember hearing shots behind our house; that's when they sent more police," she said.

Berman recalls the initial orders to stay indoors, followed by the taunts at school and the friendships that dissolved.

Reynolds said, "I read somewhere where people assumed that since Jack Ruby carried a gun, that your father must carry a gun, too."

Berman replied, "I had a friend, and she was not allowed to come to my house any more; since my uncle had a gun, my father would have a gun, and it wasn't safe."

Her father was Earl Ruby, Jack's youngest brother, the owner of a cleaners in Detroit.

"I remember my father talking about my uncle was very patriotic, loved President Kennedy, and was really, really upset when Kennedy was shot and killed."

Jack Ruby never denied his guilt. How could he? The whole world saw him do it.

The jury found Ruby "guilty of murder with malice." He was sentenced to death.

Jack Ruby died of cancer while in custody in 1967. But for Earl Ruby, though, there was still work to do.

Earl Ruby said in 1991, "[Jack] didn't want to kill Oswald in the first place. He only wanted to hurt him."

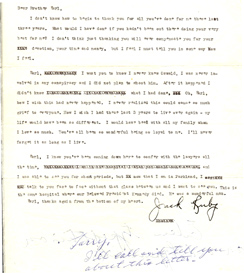

Many of the telegrams that Jack Ruby received while in jail were laudatory.

"Congratulations." "Job well done." "God bless you." "Mazel tov." "Congratulations for your most heroic and dynamic act."

Joyce's home became a repository for Jack Ruby mementos after her father's death in 2006.A letter from Jack Ruby to his brother, written three years after that weekend in Dallas, reads, "I was never involved in any conspiracy and did not plan to shoot him. After it happened, I didn't know what I had done. . . . Oh Earl, how I wish this had never happened." It was signed "Jack Ruby" -- almost, said Reynolds, as if he knew the historic value of such a letter.

After reading through so much of this stuff . . . and piecing together what she was told of her uncle . . . a conspiracy seems very unlikely to her. And she pointed us to a very mundane consideration.

Today, Joyce Berman is no different than anyone else who lived through those days half a century ago -- still pondering the same old question, without a satisfying answer.

"I wonder, like, why was he there? I mean, the press, okay. And the police escorting Oswald, okay. I mean, there are certain people that are going to be there. Why was he allowed to be there? I have a question about that."

Complete CBSNews.com coverage: JFK Assassination - Includes galleries, articles, and streaming video of CBS News' original broadcasts from four days in November 1963.