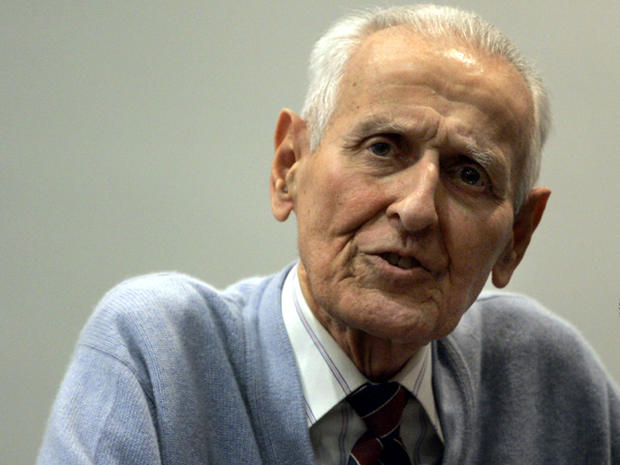

Jack Kevorkian dies, but physician-assisted suicide lives on

(CBS/AP) Jack Kevorkian has died, but the cause he long championed - physician-assisted suicide - lives on.

The ghoulish-but-folksy physician died Friday not by his own hand but at a hospital in Royal Oak, Mich., where he was being treated for pneumonia and kidney problems. He was 83.

Kevorkian, nicknamed "Dr. Death," became an outspoken and often controversial proponent of patients' right to take their own lives, gaining international notoriety in a 1998 60 Minutes interview, which showcased one of the suicides in which he participated.

"Somebody has to do something for suffering humanity," Kevorkian explained. "I put myself in my patients' place. This is something I would want."

PICTURES - 8 signs someone is at risk for suicide

Among the patients whose suicide was Kevorkian facilitated was Janet Adkins, a 54-year-old Portland, Ore. woman who died in 1990 after Kevorkin hooked her up to a "suicide machine" he had built using parts scavenged from flea markets. Altogether, Kevorkian helped end the lives of 130 people with ailments ranging from multiple sclerosis and cancer to Lou Gehrig's disease.

One of Kevorkian's dreams was to establish "obitoriums," places where people could go to end their lives. He didn't live to see that happen, but physician-assisted suicide is edging closer to the medical mainstream.

Washington, Oregon, and Montana now allow physician-assisted suicide. In addition, several professional organizations now endorse an approach to end-of-life care known as "aid-in dying," according to Barbara Coombs Lee, president of Compassion & Choices, a nonprofit advocacy group. The American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine and the American Medical Women's Association released position statements in favor of the practice. The basic idea of aid-in-dying, Lee told CBS News, was for doctors to give patients a choice while in palliative care or hospice - that if they suffer despite trying other end-of-life therapies, they could end their lives.

But not everyone agrees with Lee, that doctors should be serving up life-ending medication for their suicide-minded patients.

Stephen Drake, a research analyst for a disability advocacy group called Not Dead Yet, said physician-assisted suicide often ends up taking the lives not of terminally ill patients, but of people who had better options.

"Suicide-prevention people have written off the old, ill, and disabled," he told CBS News.

What do you think? Should patients be able to end their lives with the help of a doctor? Or was Jack Kevorkian dead wrong?