Advances in IVF testing spurring debate over "mosaic" embryos

This month marks 40 years since the birth of the first baby conceived through in vitro fertilization, Louise Joy Brown. Since then, more than eight million babies have been born using the technique.

Advances in IVF testing have improved outcomes for couples with infertility. But these advances are also spurring debate over what's called "mosaic" embryos. Those are embryos with both normal and abnormal cells.

Mosaic embryos could not be detected before the improved genetic screenings. Some fertility experts are torn over whether mosaic embryos should be implanted. But for patients struggling with fertility and with limited options, mosaic embryos may offer new hope.

For Mary Jo and Shane Dunn, the embryos were their last chance at a dream of having a family. In 2015, the Dunns lost their only child, Luke, to a rare cancer at 17 months old.

"I just didn't imagine continuing to live without my baby," Mary Jo told CBS News' Dr. Tara Narula. "It was just excruciating pain."

"I was determined that this wasn't gonna be the thing that was going to ruin us," Shane said.

The Dunns decided to try for another child, but in their mid-40s, knew conceiving would be hard. They endured nearly two years of failed IVF treatments.

After six egg retrievals and $70,000, their hopes of a child came down to two remaining embryos Dunns initially set aside. The reason: they didn't test genetically normal. In the end though, those were the only two embryos that turned out perfect.

Twin girls, Riley and Kelsey, were born nine months later.

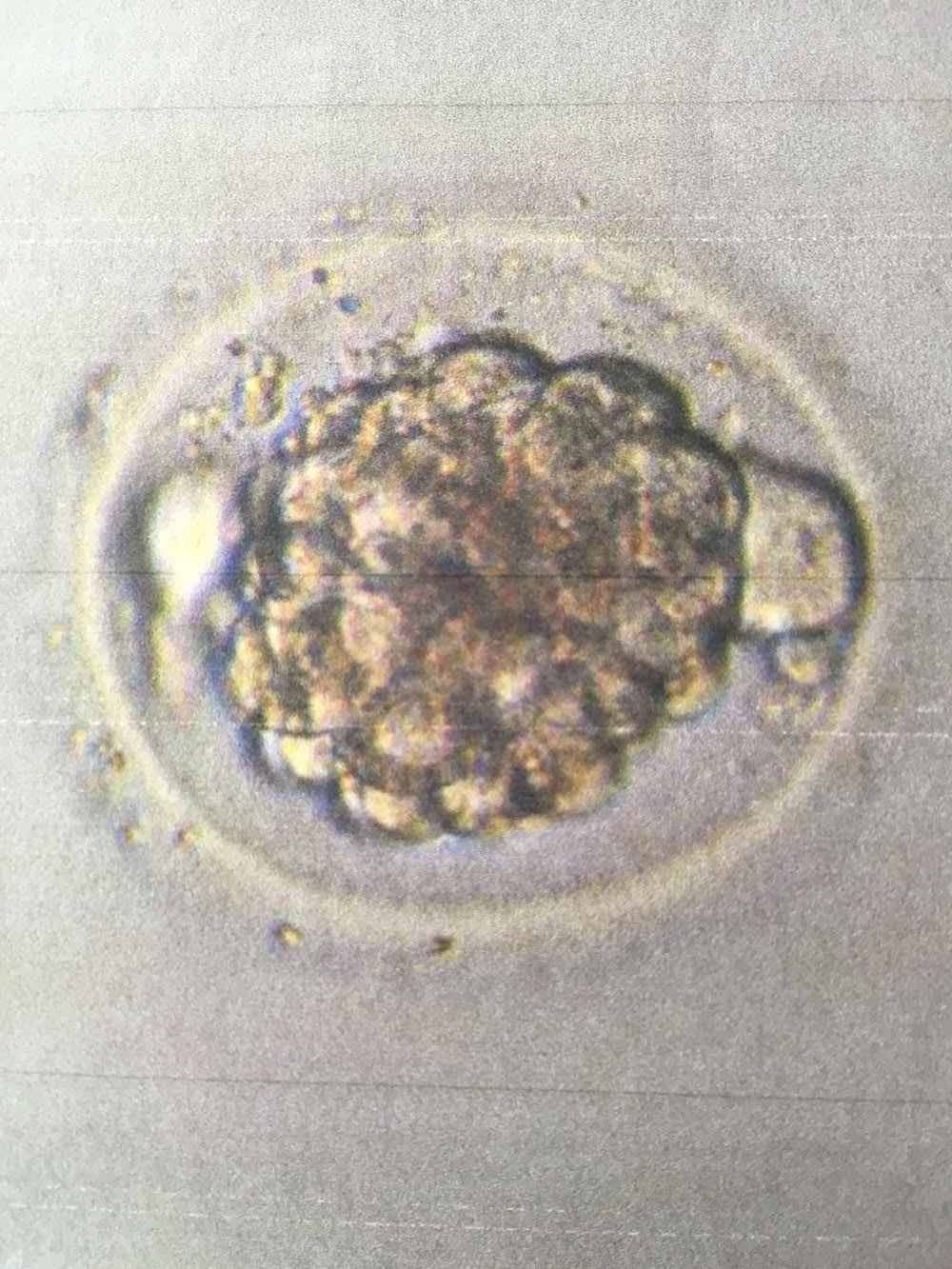

The embryo testing the Dunns opted for is called PGS testing, preimplantation genetic screening. It takes a biopsy of just a handful of cells from the outer layer of an embryo to determine if it is chromosomally healthy. It's then classified as normal or abnormal.

In 2014, advances in this screening made it possible to detect when an embryo has a mix of normal and abnormal cells. When they do have the mix, they are called mosaic embryos.

The Dunn twins grew from mosaic embryos. Doctors believe, in some cases, those abnormal cells can self-correct or be pushed to the placenta, leaving the embryo healthy. But because the biopsy is small, the challenge is knowing the extent of abnormality and what that means for pregnancy. The Dunns heard the risks when doctors explained what mosaic embryos were.

"The mosaic embryo can either fail to implant and you could miscarry, you could have a child with birth defects, or you could have a perfectly healthy baby," Mary Jo said. "That's with every pregnancy, really."

But the decision to implant these embryos using IVF is spurring debate among fertility experts.

"Mosaic embryos are not abnormal embryos. Abnormal embryos don't make babies or pregnancies," said Dr. Jamie Grifo, director of NYU Langone Fertility Center. "Mosaic embryos have potential. They don't have the same potential as a chromosomally normal embryo. But they can make babies."

Grifo says mosaic embryos carry a higher risk of miscarriage.

"We have to learn which ones are more likely to make the baby and which ones are less likely and then patients get to decide whether to use that embryo," Grifo said.

According to one study, mosaic embryos create a baby roughly one-third of the time. Out of 78 transferred mosaic embryos, the study found 24 healthy babies were born.

But some doctors like Mandy Katz-Jaffe, scientific director at the Colorado Center for Reproductive Medicine, caution against implanting mosaic embryos. They point to a lack of long-term studies of babies born from them.

"We really don't know the answer to the full question of what is the probability that a mosaic embryo will result in either an affected baby or a healthy baby." Katz-Jaffe said.

The Dunns believe they are living proof of its value.

"If one person sees this interview and decides, 'You know what, I have a mosaic embryo that I was questioning whether or not to transfer.' Here we are," Mary Jo said. "It's worth taking that chance."

The lab that tested the Dunns' embryos, Cooper Genomics, say they are seeing a growing trend in fertility doctors requesting mosaic reporting. But many of the roughly 400 clinics nationwide still only report normal or abnormal results. A committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine found earlier this year that they didn't have enough information to form an opinion on what percentage of normal cells is needed to be recommended for use.