Is your city ready for the switch to electric vehicles?

How prepared is your hometown for the electric vehicle revolution?

Atlanta this week became the latest city to pass an ordinance that requires 20 percent of the spaces in all new commercial and multifamily parking structures be "EV ready."

It also requires new residential homes be wired to easily install EV charging stations. The ordinance takes immediate effect.

"Atlanta has taken a historic step to increase our EV readiness and to ensure we remain a leading city in sustainability," Mayor Kasim Reed said in a statement.

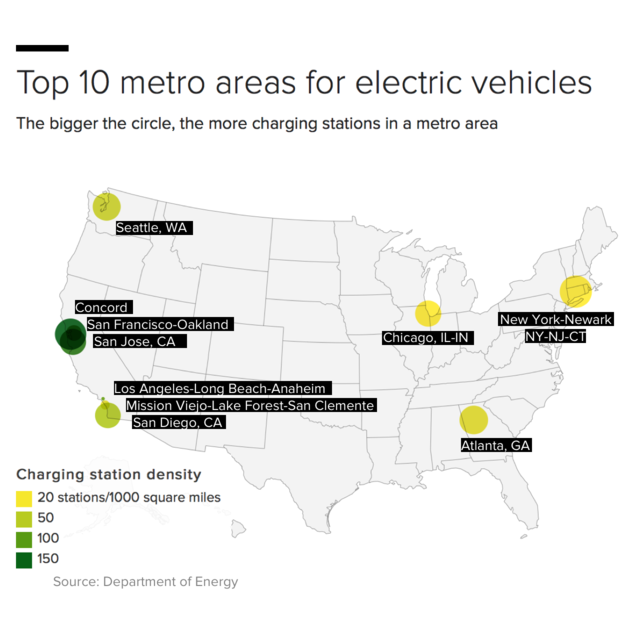

Atlanta is hardly alone. Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Jose and New York/Newark are listed above Atlanta in the top five urban areas with electric vehicle registrations, according to a 2017 U.S. Department of Energy report. Cities this summer banded together to pledge to cut carbon emissions as a counter to President Trump's withdrawal from the Paris climate accord. Encouraging electric vehicle use is one of the measures already underway.

On the state level, 45 states and Washington D.C. offered incentive for hybrid and other electric vehicles, including tax credits, rebates, fleet acquisition goals or exemptions from emissions testing as of September, according to an analysis from the National Conference of State Legislatures.

And it's no wonder governments are working to meet increasing demand.

A recent report from IHS Market forecasts that electric vehicles will account for more than 30 percent of new cars sold in key automotive markets by 2040 -- up from just 1 percent of new car sales in 2016 -- as consumers and governments seek ways to cut emissions and ensure cleaner air for residents.

Gasoline and diesel-powered cars will still account for a majority of vehicles sold in the four "key major markets" -- China, Europe, India and the U.S. -- but will fall to 62 percent from 98 percent last year, IHS estimated in its "baseline" scenario.

Globally, there may be 1 billion electric vehicles by 2050, a recent report from Morgan Stanley estimated. That would mean a shift to 90 percent of all new vehicle sales.

One reason for the acceleration, no matter what the estimate, may be a widening adoption of autonomous vehicles, IHS said. What's more, battery costs are coming down, Morgan Stanley noted, dropping 30 percent per year for the past five years.

And the vehicles are getting sexier and more practical, at least aesthetically. Last week, Tesla's Elon Musk revived that company's roadster model, boasting a 620-mile range and acceleration from zero to 60 mph in 1.9 seconds. The surprise reveal came at an event to unveil the newest model of Tesla's decidedly less racy, but no less exciting to some, semi-truck.

But wait, don't electric vehicles cause more energy to be generated by higher-emission plants like those that burn coal? On balance, an analysis from the Union of Concerned Scientists conducted last year concluded, the answer is no.

More than two-thirds of Americans live in areas where "powering an electric car on the regional electricity grid produces lower global warming emissions than a gas-powered or hybrid car getting 50 miles per gallon," the group said on its website.

Subsidies and incentives are helping spur consumer adoption.

On the national level, incentives include a federal tax credit of up to $7,500. That credit expires once 200,000 qualified plug-in vehicles have applied. And in states like Massachusetts, incentives include grants for agencies, including schools, cities, towns and public colleges and universities, to get EVs and charging stations. That creates demand for both the vehicles and the infrastructure.

Electric vehicles have been under development since the 1800s and seemed to gain some popularity at the turn of the last century, according to the Edison Technical Center. As the 20th century ground on, combustion-engine vehicles were developed and electric vehicles didn't take hold.

The modern era is marked by Toyota's 1997 introduction of the Prius hybrid vehicle in Japan that year. It became globally available in 2000, according to the Department of Energy's timeline. Tesla, incorporated in 2003, received a $465 million DOE loan in 2010 to develop its Fremont, California factory.

Tesla has sold the most electric vehicles in the U.S. though September, but would have to sell another 80,000 before its federal credit allotment for consumers begins to phase out, according to the NCSL. Traditional manufacturers, like Ford and GM, have followed with their own EV models.

About 15 million plug-in electric vehicles will be on the road in the U.S. by 2030, according to a September report from the U.S. Department of Energy.

That means roughly 600,000 non-residential plugs and 25,00 DCFC (direct current fast charging) plugs are needed to satisfy demand, the DOE says.

About 4,900 DCFC stations are needed across cities with another 3,200 DCFC stations needed in towns to cover communities that represent 81 percent of the population, the DOE estimated. That would ensure drivers aren't farther than three miles from a DCFC charging station.