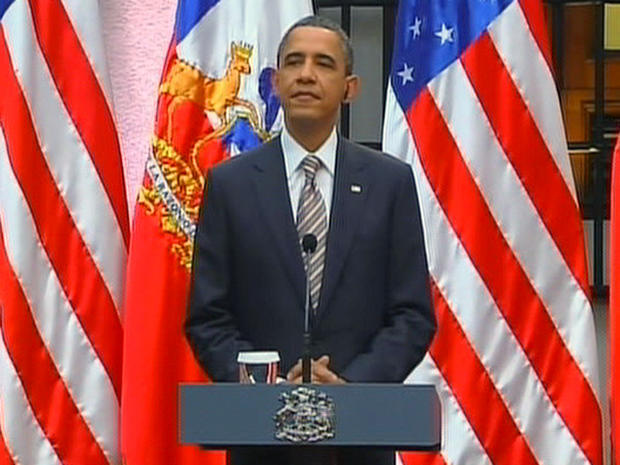

Is Obama's Libya offensive constitutional?

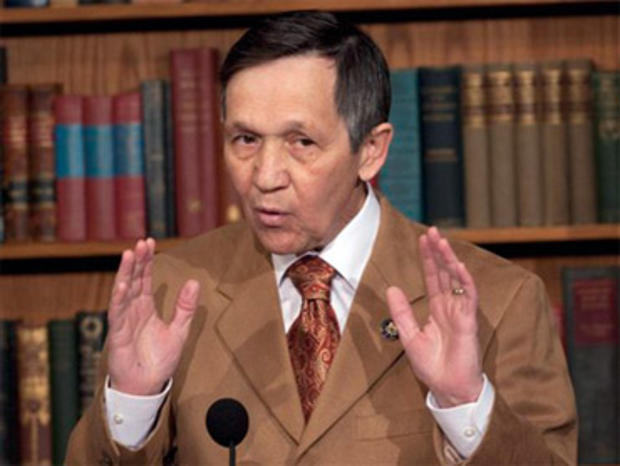

Members of Congress have been expressing increasing frustration over President Obama's decision to launch missile strikes against Libya without congressional approval. Liberal Democratic Rep. Dennis Kucinich suggested the action was impeachable; Sen. Jim Webb, another Democrat, complained on MSNBC that Congress has "been sort of on autopilot for almost 10 years now, in terms of presidential authority, in conducting these types of military operations absent the meaningful participation of the Congress."

Some Republicans, meanwhile, are also calling for congressional approval if America is going to war, among them Sen. Richard Lugar. GOP Rep. Walter Jones has complained that Congress has effectively been "neutered."

"I wish the president had not gone into Libya without first coming to Congress," Jones told Politico. "We have for too long, as a Congress, been too passive when it comes to sending our young men and women to war."

Added Republican Rep. Roscoe Bartlett: "The United States does not have a King's army. President Obama's unilateral choice to use U.S. military force in Libya is an affront to our Constitution."

Which raises the question: Is it Congress or the president that has the power to authorize military action?

The answer is that, to some extent, they both claim it. The Constitution, in Article I, Section 8, explicitly states that "The Congress shall have Power To...declare War." But in Article II, Section 2, the Constitution says that "The president shall be Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States." So while only Congress can technically declare war, the president is in charge of the military - and can decide when and where it is deployed.

Which helps explain why America hasn't actually declared war since World War 2. President Harry Truman didn't go to Congress for a formal declaration of war in Korea, mandating that the U.S. involvement was simply a "police action." That example has been followed in the years since.

In 1973, in response to the Vietnam War, Congress passed the War Powers Act, which mandates that a president obtain congressional approval within 90 days of introducing troops into battle. (It also mandates that they explain the action to Congress within 48 hours.) Yet it too has largely been ignored, in part because it does not provide any recourse if a president violates it. On Monday, Kucinich said he would try to use Congress' power of the purse to stop the U.S. intervention in Libya, saying he would introduce an amendment to defund the action.

Others on the left, meanwhile, are warning that the current situation sets a dangerous precedent.

"To put it crudely: as a matter of logic, if President Obama can bomb Libya without Congressional authorization, then President Palin can bomb Iran without Congressional authorization," wrote Robert Naiman of Just Foreign Policy. "If, God forbid, we ever get to that fork in the road, you can bet your bottom dollar that the advocates of bombing Iran will invoke Congressional silence now as justification for their claims of unilateral presidential authority to bomb anywhere, anytime."

Critics of Mr. Obama's action are using the president's own words against him; in a 2007 interview with the Boston Globe, the then-senator said this about a president's authority to bomb Iran without approval from Congress: "The president does not have power under the Constitution to unilaterally authorize a military attack in a situation that does not involve stopping an actual or imminent threat to the nation."

"As commander in chief, the president does have a duty to protect and defend the United States," he added. "In instances of self-defense, the president would be within his constitutional authority to act before advising Congress or seeking its consent."

Mr. Obama sent a letter on Monday notifying Congress he had acted in Libya, in conjunction with the War Powers Act's 48 hours requirement. He said he authorized the action as part of a response authorized under the U.N. security council demanding that Libyan leader Moammar Qaddafi change course or face consequences; the goal, he said, is "to prevent a humanitarian catastrophe and address the threat posed to international peace and security by the crisis in Libya."

"I have directed these actions, which are in the national security and foreign policy interests of the United States, pursuant to my constitutional authority to conduct U.S. foreign relations and as Commander in Chief and Chief Executive," he wrote.

24 more Tomahawk missiles launched over Libya