Is immigration a land mine for GOP ahead of midterms?

The chaos among House Republicans this past week on immigration shows just how problematic and risky the issue is for a party that badly needs unity heading into the elections in November that will decide control of Congress.

GOP leaders thought they had found a way by Friday morning to make the party's warring conservative and moderate wings happy on an issue that has bedeviled them for years.

Conservatives would get a vote by late June on an immigration bill that parrots many of President Trump's hard-right immigration views, including reductions on legal immigration and opening the door to his proposed wall with Mexico. Centrists would have a chance to craft a more moderate alternative with the White House and Democrats and get a vote on that, too.

But it all blew up as conservatives decided they didn't like that offer and rebelled. By lunchtime Friday, many were among the 30 Republicans who joined Democrats and scuttled a sweeping farm and food bill, a humiliating setback for the House's GOP leaders, particularly for lame-duck Speaker Paul Ryan, R-Wis.

The conservatives essentially took the agriculture bill hostage.

They said they were unwilling to let the farm measure pass unless they first got assurances that when the House addresses immigration in coming weeks, leaders would not help an overly permissive version pass.

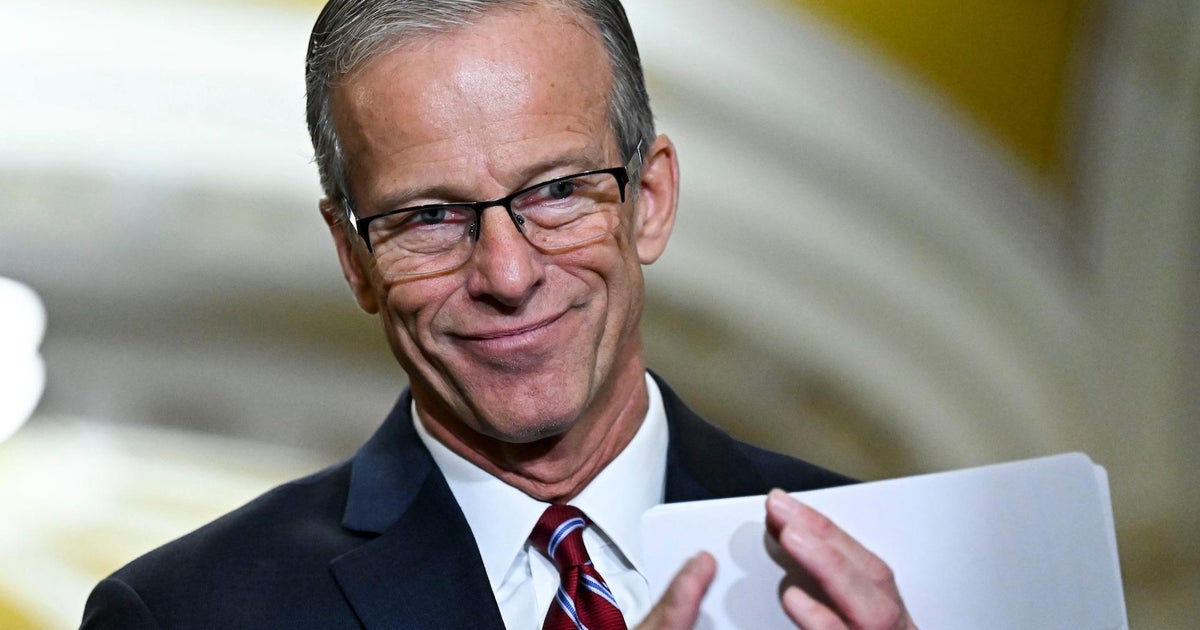

Rep. Jeff Denham, R-Calif., a leader of the moderates, said his group would try to write a bill that would let young "Dreamer" immigrants in the U.S. illegally stay permanently — a position anathema to conservatives — and toughen border security.

A moderate immigration package "disavows what the last election was about and what the majority of the American people want, and the people in this body know it," said Rep. Scott Perry, R-Pa. He's a member of the hard-right House Freedom Caucus, many of whose members opposed the farm bill.

"It's all about timing unfortunately and leverage, and the farm bill was just a casualty, unfortunately," Perry said.

Denham and his allies were also unwilling to back down. He told reporters that the conservatives "broke that agreement," and his group would pursue bipartisan legislation.

"I'm disappointed in some colleagues who asked for a concession, got the concession and then took down a bill anyway," Denham said in a slap at the Freedom Caucus. Denham said the concession was a promised vote on the conservative immigration bill by June, though conservatives said they never agreed to that.

Such internal bickering is the opposite of what the GOP needs as the party struggles to fend off Democratic efforts to capture House control in November. Democrats need to gain 23 seats to win a majority, and a spate of Democratic special election victories and polling data suggests they have a solid chance of achieving that.

Republican leaders and strategists think their winning formula is to focus on an economy that has been gaining strength and tax cuts the GOP says is putting more money in people's wallets.

Immigration is a distraction from that message — and worse.

On one side are conservatives from Republican strongholds, where many voters consider helping immigrants stay in the U.S. to be amnesty. On the other are GOP moderates, often representing districts with many constituents who are Hispanic, moderate suburbanites or are tied to the agriculture industry, which relies heavily on migrant workers.

A look at the 20 Republicans who have signed a petition by GOP moderates aimed at forcing House votes on four immigration bills is instructive.

Of the 20, nine are from districts whose Hispanic populations exceed 18 percent, the proportion of the entire U.S. that is Hispanic. Denham's Central California district is 40 percent Hispanic, while five others' constituencies are at least two-thirds Hispanic.

In addition, 11 of the 20 represent districts that Democrat Hillary Clinton carried over Mr. Trump in the 2016 presidential election.

The petition drive, led by Denham and GOP Rep. Carlos Curbelo, whose South Florida district is 70 percent Hispanic, is opposed by party leaders because the winning bill probably would be a compromise backed by all Democrats and a few dozen Republicans. That would enrage conservatives, perhaps prompting a rebellion that could cost House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., his goal of succeeding Ryan as speaker.

All that trouble would be for legislation that still faces long odds of becoming law.

Even if a formula is discovered that could pass the House, it could run aground in the Senate, where four immigration bills died in February and Democrats can use the filibuster to scuttle any bill they dislike. Those defeats led Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., to say he wouldn't revisit immigration unless a bill arose that could actually pass this chamber.

Mr. Trump's willingness to sign immigration legislation also remains in question after a year that has seen his stance on the issue veer unpredictably.