Lessons learned from Ingenuity Mars helicopter will play into designs for follow-on craft

Nearly a year after NASA's Ingenuity helicopter crash landed on Mars following an extended, remarkably successful mission, engineers have determined the most likely culprit: Flight over sand drifts so featureless that on-board sensors could not determine the helicopter's orientation and velocity.

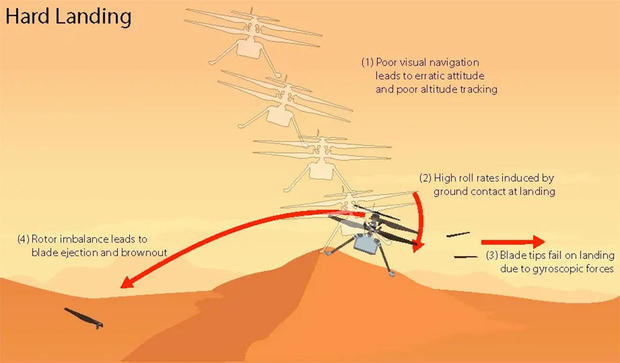

The result was a "hard" sideways landing on a steep slope that spun Ingenuity about so fast its rotors, spinning at nearly 400 mph to provide lift in the ultra-thin martian atmosphere, suffered structural failure. One broke off and the others were severely damaged.

Håvard Grip, Ingenuity's first pilot, said in an interview Wednesday that lessons learned from Ingenuity's 72nd and final flight on Jan. 18 will be fed into designs for more powerful Mars helicopters now being studied at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory where Ingenuity was built.

"We're working very actively right now on what that might look like," Grip said in an interview. "We're developing this large aircraft concept with six rotors and 36 blades that could fly its own science payload around Mars. So that is kind of where our focus is in the helicopter world right now."

During a briefing Wednesday at the American Geophysical Union's annual meeting in Washington, D.C., Teddy Tzanetos, the Ingenuity project manager, discussed the six-rotor Mars Chopper concept, a rotorcraft that would be 20 times heavier than Ingenuity and could fly up to two miles per day carrying several pounds of science instrumentation.

Ingenuity "became the first mission to fly commercial off-the-shelf cellphone processors in deep space," Tzanetos said in a NASA news release. The mission showed "that not everything needs to be bigger, heavier and radiation-hardened to work in the harsh Martian environment."

Carried to Mars by NASA's Perseverance rover, Ingenuity was dropped to the surface of the red planet in April 2021 and made its initial flight two weeks later. Built primarily to find out if helicopters could fly in the cold, thin atmosphere, Ingenuity was expected to make five flights over 30 days as a proof of concept.

The the surprise of virtually everyone, it ended up making 72 flights over nearly three years, repeatedly scouting ahead of Perseverance while logging more than two hours of flight time and traveling a cumulative 10.7 miles at altitudes up to nearly 80 feet before its final flight on Jan. 18.

During that flight, Ingenuity climbed to an altitude of about 40 feet, hovered and captured photographs of the surrounding terrain and began to descend 19 seconds after takeoff. Thirteen seconds after that, the helicopter was back on the ground, but contact had been lost.

Communications through Perseverance were restored the next day, and six days after the flight, the rover sent back pictures showing the helicopter had sustained major damage to its rotors.

Flight controllers initially suspected Ingenuity made a hard landing at a steep angle, causing its high-speed rotors to hit the ground.

But the most likely scenario, Grip said, is that the helicopter was unable to determine its horizontal velocity as it flew over virtually featureless sand and touched down while moving sideways at a speed well above its design constraints.

"We also landed on a steep slope, probably the steepest slope that we have encountered in all of our flights," he said. "The combination of the two lends itself well to what our most likely scenario hypothesizes.

"When it contacted the ground, it sort of whipped around quickly in order to align itself with the surface. That forces the helicopter to rotate around in roll and pitch, and because this rotor is stiff, the rotor has to sort of follow more or less instantly, and that puts a lot of bending moments on the blades."

Those bending moments, or forces, were extreme because the tips of the rotors were moving so fast. The tips of the blades broke away, putting the rotor system out of balance. That, in turn, resulted in enough vibration to cause one rotor to break off at its root. Grip said none of the blades touched the surface during the landing.

In yet another surprise for flight controllers, Ingenuity came to a rest on its landing legs with its small solar array pointed skyward. While it could no longer fly, it continued to relay martian weather reports to Perseverance through last November when the rover finally moved too far away to maintain the radio link.

"I always pictured that a bad landing would end with, you know, the thing just in 1,000 pieces on the surface," Grip said. "So the fact that it's upright and talking to us (was) not at all what I would have anticipated."