Why India may be "the only country that has something to show as progress at COP27," despite its coal habit

New Delhi — When the COP27 United Nations climate conference kicks off this weekend in Egypt, India will likely approach the international gathering with a well-earned boast about its success in going green and an appeal for more help to continue down that path. But despite significant strides that one analyst says have made India the only nation with anything to brag about, it may find an international community with little appetite for generosity.

Ahead of the climate summit, and clearly aiming to impress, India has set itself tougher targets for cutting carbon dioxide emissions and increasing its clean energy generation capacity by 2030, largely off the back of significant progress in its solar power industry.

Setting the bar higher

As all nations were asked to do ahead of COP27, India submitted its updated "nationally determined contributions" (NDCs) to the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) in August.

Under the terms of climate treaties signed by the COP nations, every country must submit its own goals for reducing emissions and explain how they'll be met — and every year the nations are expected to show progress and make their goals more ambitious. With India's new NDCs, it has pledged to reduce the intensity of the emissions from its national economic output by 45% by 2030, compared to its 2005 level. The target was previously set at 30%.

India has also promised to increase its total share of installed renewable power capacity to 50% by 2030. Currently it's less than 30%, as 70% of India's electricity still comes from coal.

The country has also added a new target: It has pledged to create a "carbon sink," to absorb the equivalent of 2.5 to 3 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide by 2030, through mass-tree planting.

Besides these official commitments, the Indian government also released an ambitious draft National Electricity Plan (NEP) in September. The plan is a policy document released every five years that guides the power sector's expansion.

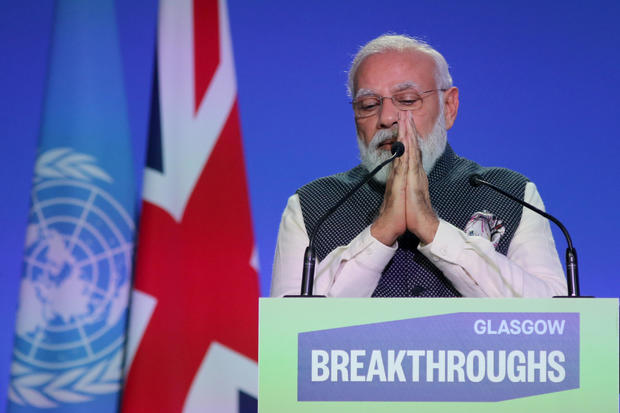

This year's plan seems to exceed commitments made by Prime Minister Narendra Modi at COP26 in Glasgow last year. The NEP aims to achieve 57% renewable capacity by 2027 and 68% by 2032. It also plans for a 24% increase in solar power production targets for 2027 compared to the previous plan.

A solar powerhouse?

India has set its ambitious targets based largely on significant progress made in its solar energy sector. The country has a current solar energy generation capacity of 59 gigawatts. That makes it the fifth-highest producer, behind the U.S. and China, but given the country's solar capacity growth rate of 47% annually between 2016 and 2021, many hope to see it emerge quickly as a global hub for solar energy.

In September, online retail giant Amazon announced its first three solar farm projects in India, which it said would produce a total of 420 megawatts of clean energy. The company will also set up 23 new solar rooftop projects on its fulfilment centers across 14 Indian cities.

"This indicates the fact that corporates are now really embarked on their decarbonization journeys," said Sumant Sinha, founder, chairman and CEO of ReNew Power, which is developing one of the solar farms for Amazon, a 210 MW plant in Rajasthan.

"Almost a quarter of our new capacity is being directly picked up by corporates. A couple of years ago, this was just two or three percent," he told CBS News. "They are doing it for two reasons: One is that they want to decarbonize their own operations, and two, because it's cheaper for them."

Several other major global corporations are also investing in India's solar industry. Netherlands-based SHV Energy, a big player in the oil and gas industry, has acquired a majority stake in Sunsource Energy, one of the top solar companies in India, and Malaysia-based Petronas has also acquired a leading solar rooftop company in India.

Indian entrepreneurs are also investing in medium and micro-scaled solar power projects, and the government is backing a solar energy program for the country's vast agricultural sector, paving the way for the installation of 3.75 million solar-powered irrigation pumps over the next three years.

"There is no way you can exclude India from the energy mix in the global scenario from now on," Subrahmanyam Pulipaka, CEO of the National Solar Energy Federation of India, told CBS News. "I believe India will end up achieving the solar capacity target of 350 GW earlier than 2030."

Touting success, and seeking help

India emits more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than every other individual nation apart from China and the U.S. With a growing economy and some 1.35 billion people, it has faced pressure from more developed countries to phase out coal and end subsidies for oil and gas.

While India's energy transition is happening at an impressive rate, it argues that abandoning fossil fuels too quickly would risk its economic development, and in a nation where so many remain mired in poverty, it can't afford that option. At least not without significant financial help from wealthier nations.

"India's energy needs will grow, which means that in the short run, its emissions almost certainly will also grow, whether [for] five or 10 years, that is unclear," Navroz Dubash, a professor with the India-based Centre for Policy Research, told CBS News. He said that for the next decade or two, India should stress that it is "committed to a low-carbon future, but one that allows us to develop and meet our energy needs."

India has a relatively good report card to show off at the upcoming COP27 summit, and it will tout the success of its energy transition thus far to seek more global funding to decarbonize and mitigate the dangerous impacts of climate change, experts told CBS News.

"India has demonstrated that in the past, it has been able to add more clean energy alternatives and has set up huge ambitions," Vibhuti Garg, an energy economist at the Institute for Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), told CBS News.

"India is the only country that has something to show as progress at COP27," said Subrahmanyam Pulipaka, CEO of the National Solar Energy Federation of India. "Our renewable energy generation has not decreased but increased, even during the COVID pandemic and [Ukraine] war."

At the last year's COP26 in Glasgow, Prime Minister Narendra Modi sought $1 trillion in climate finance for India over the coming nine years, to help it meet its 2030 targets.

India did see an increase in renewable energy investments last year compared to previous years, but Garg, the IEEFA economist, said the country would need "about two to three times more investment to meet the 2030 target."

A recent report by the New York-based Asia Society Policy Institute estimated that India would need $10.1 trillion in investments to achieve its pledge of complete carbon neutrality by 2070.

But with the Ukraine war creating huge disruptions in the global energy supply chain and fueling geopolitical uncertainty, it's not clear if developing countries like India will be able to secure significant new financial commitments at COP27.

Already developed nations have broken a promise they made at COP15 to ringfence $100 billion annually to help developing countries decarbonize and deal with the impacts of climate change.

"And now that some of these developed countries are facing crises like rising prices of food and fuel in their own countries, things are becoming worse," Garg told CBS News. "So, I don't know how much finance they are going to make available to other countries to help them transition."