"Incredibly moving" audio from El Faro's final hours

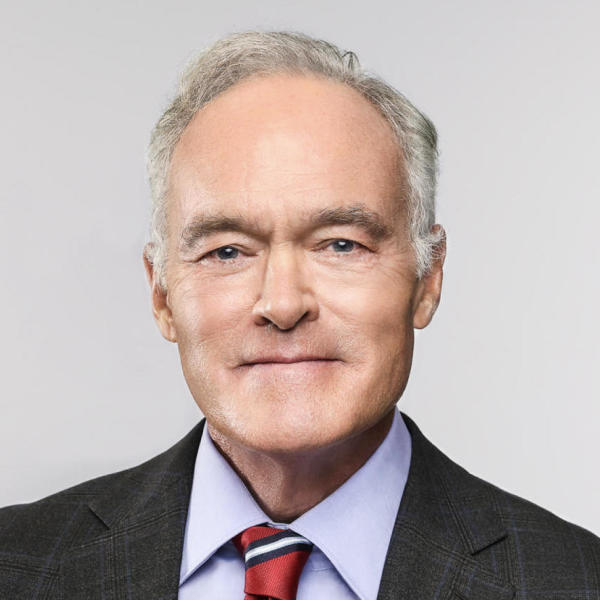

The following script is from “Voices of the Lost,” which aired on March 5, 2017. Scott Pelley is the correspondent. Patricia Shevlin and Miles Doran, producers.

Thirty-three men and women were killed when the American ship El Faro vanished in the Bermuda Triangle. In Spanish, El Faro means “the lighthouse” but, when she sank in 2015, no beacon led to her resting place. The families of the crew were desperate for answers. Why did the captain sail into a hurricane? Why couldn’t the ship survive? Getting to the bottom of a mystery lying deeper than the Titanic was up to the National Transportation Safety Board. Last year, we showed you the hunt for El Faro. Now, investigators have a wealth of new evidence because they have heard the voices of the lost.

Exploring the mystery, off the Bahamas, took 10 months of patience, millions of dollars, and technology able to reach three miles into a world of total darkness. We were aboard the U.S. Navy’s ‘Apache’ that discovered the wreck in October 2015 -- 30 days after El Faro went down.

The ship was found upright. But from the mangled name on her stern, to her bow, all 791 feet, revealed the wounds of a savage beating. She had collided with a hurricane named Joaquin. This is captain Michael Davidson’s last report.

“This accident was unique in the fact that we didn’t have any survivors to interview that would enlighten us to the events and the situation that took place aboard the vessel as they approached the storm.”

Davidson, phone call: I have a marine emergency…We had a – a - a hull breach. A scuttle blew open during a storm. We have water down in 3-hold with a heavy list. We’ve lost the main propulsion unit. The engineers cannot get it going.

Captain Davidson was a 30-year veteran of the sea. Married with two daughters. His crew included third mate Jeremie Riehm, on the far right, married with a son and a daughter. Danielle Randolph, the second mate, had dreamed of the sea since she was a little girl. And the chief engineer, Richard Pusatere, had a wife and a baby girl.

Brian Young: This accident was unique in the fact that we didn’t have any survivors to interview that would enlighten us to the events and the situation that took place aboard the vessel as they approached the storm.

Scott Pelley: You were missing a lot of pieces from the jigsaw puzzle.

Brian Young: Absolutely.

The key piece of the puzzle had been denied Brian Young, the safety board’s lead investigator. This was El Faro’s voyage data recorder, like the voice recorders on airliners. It captures conversations on the bridge. And it should have been on top of this structure called the ‘house.’ But the top of the house, the bridge and deck below, had been ripped away. They were eventually found half a mile from the wreck. But still there was no sign of the voyage data recorder, also called a “VDR.” The search vessel Apache ran out of time.

Eric Stolzenberg: The big challenge was locating the VDR which was only about a foot by eight inches.

Safety board investigator Eric Stolzenberg returned six months later, in April of last year, with the research vessel Atlantis. Sonar found 150 targets. And they began to visit each one.

Eric Stolzenberg: So in a way, you’re stumbling in the dark and even though something should be right in front of you, it isn’t, it can be 10 or more meters off to your left or right.

Scott Pelley: It’s like crawling on your hands and knees with the flashlight?

Eric Stolzenberg: That’s a good description, yes.

After five days, their light flashed on a strip of reflective tape on the VDR. Four months later special equipment was brought in to grab it. No commercial recorder had ever been recovered this deep where the pressure is nearly 7,000 pounds per square inch.

Jim Ritter: This capsule was contained inside the larger capsule.

Salvaging the clues was up to Jim Ritter’s lab at the NTSB in Washington.

Jim Ritter: This is the actual circuit board that contains the memory. This tiny device with these two memory chips right here contain the entire 26 hours of information from the voyage data recorder.

This card captured the sound from six microphones on the bridge. By law, the audio is never released to the public. But investigators produced a 500-page transcript.

“It was incredibly moving. We listened to the entire VDR from start to finish and at the end of it the team was completely silent. Nobody spoke.”

Brian Young: It was incredibly moving. We listened to the entire VDR from start to finish and at the end of it the team was completely silent. Nobody spoke.

Scott Pelley: What was it on the tape that moved you so much?

Brian Young: We knew when that recording was gonna end, and we knew what a tragic ending it was gonna be, whereas I know the crew did not know that. That was very difficult for us to watch that clock count down to the end of the recording.

Scott Pelley: You were listening to the voices of the lost and you knew it.

Brian Young: Yes. Yes. And that was really tough to listen to.

The recording begins the day before the disaster. El Faro was 150 miles from Jacksonville, headed south to Puerto Rico with a cargo ranging from frozen chickens to cars. Joaquin at the time was just a tropical storm but Captain Davidson ordered a course change to keep his distance. On the voyage recorder he’s heard saying to the chief mate, “This is why you watch the weather all the time.” Later he predicted, “It should be fine.” Then he corrected himself, “Not should be, we’re gunna be fine.”

Brian Young: What we have learned from the VDR is that multiple weather reports were being sent to the ship. The watch officers on the bridge were receiving weather reports that were printed out in black and white, and mostly text, and then the captain was receiving a graphically depicted weather report in his office every six hours.

Scott Pelley: Which were more accurate?

Brian Young: The ones on the bridge were more accurate in terms of time whereas the system that the captain received was six hours behind.

Scott Pelley: The weather information the captain was receiving in his office a deck below the bridge was six hours old?

Brian Young: Correct.

Scott Pelley: In a storm that is developing more rapidly than most hurricanes ever do?

Brian Young: Correct.

After the storm strengthened into a hurricane, the chief mate, Steve Shultz, suggested another course change and Davidson agreed. Davidson said, “We’ll be passing clear on the backside of it. The faster we’re goin’ the better.” Then, the captain left the bridge for eight hours. El Faro had 11 hours left.

Scott Pelley: How unusual, in your experience, for a captain to be eight hours in his cabin going into a storm like this?

Brian Young: It’s a difficult question to answer. This captain on this accident was convinced that they were on the better side of the storm already and that they were gonna beat the storm. But he was using the information he had, which was outdated, to make these decisions.

That was critical because the hurricane was getting closer, tracking farther south than forecast. At 11 p.m., third mate Jeremie Riehm called the captain in his quarters to say that in five hours El Faro would be “twenty-two miles from the center”…“with gusts to 120 and strengthening.” After 1 a.m., second mate Danielle Randolph, called the captain again to say “it isn’t looking good right now....” Twice, Riehm and Randolph suggested this new route, shown in green, but Captain Davidson declined.

Scott Pelley: Any idea what he’s doing down there? Is he asleep?

Brian Young: There were some references made by the mates after the phone call suggesting he may have been sleeping.

Scott Pelley: Why didn’t the junior officers, sensing danger, just decide to change course on their own if the captain wasn’t there?

Brian Young: All officers are taught to respect the chain of command. And to change the ship’s course without the captain’s permission is very drastic.

Second mate Randolph, sent an email to her mother, Laurie Bobillot.

Laurie Bobillot: She never wanted to worry me. But for her to send me an email during to say, “Heading straight for it. Give my love to everyone,” she knew. She knew, she was, they were, doomed. I’m sorry, but she knew.

Scott Pelley: And when you read that email at that moment?

Laurie Bobillot: I knew she was gone. I knew that was it.

At 4 a.m., after eight hours below, the captain returned to the bridge, saying he’d been “sleepin’ like a baby.” Now, the storm was upon them. They had three hours left. About the heavy seas, Davidson told the crew, “this is every day in Alaska, this is what it’s like.” But then Davidson’s ship began to fail him. Water was pouring into a cargo hold from an open hatch and a ruptured pipe. El Faro leaned into a 15 degree list, the extreme tilt of the ship caused the engine’s lubricating oil to flow away from the pump that was meant to circulate it.

Brian Young: Every indication we’ve heard from the VDR said that there was a loss of lube oil pressure to the engine.

Scott Pelley: So now the oil isn’t circulating in the engine.

Brian Young: And the engine has safety shutdowns. If there is no oil, the engine will shut itself down.

Scott Pelley: They are dead in the water.

Brian Young: And at the mercy of the sea.

El Faro was battered by waves as high as 30 feet. Captain Davidson ordered chief mate Steve Shultz to investigate the flooding in the hold. Richard Pusatere, the chief engineer, was fighting to restart the engine. In the audio, the crew on the bridge seems calm, deliberate. One makes coffee and another says “give me the Splenda, not the regular sugar.” They had 50 minutes left.

Brian Young: They weren’t able to keep up with the water comin’ in. The list is gettin’ worse. The engine has failed. They’re running out of options.

At 7:12 a.m., the captain ordered second mate Randolph to send a distress message. Cargo containers crashed overboard. The bow went under.

Brian Young: The abandon ship signal is sounded, and the captain directs everybody to leave the ship.

But Davidson would not leave the bridge. A crewman was trapped there. The list was so great that the man couldn’t climb up to the exit.

Scott Pelley: Is there panic?

Brian Young: We only hear what’s on the bridge, but the captain was extremely calm right to the end.

The crewman said, “you’re gonna leave me.” “I’m not leavin’ you, Davidson said, “let’s go.” “I can’t,” said the seaman, “I’m a goner.” “No you’re not,” Davidson urged, “let’s go.”

Claudia Schultz: It was not an easy thing to read.

Claudia Schultz is the widow of chief mate Steve Shultz.

Claudia Schultz: I didn’t let my kids read. Till this day, they haven’t read it.

Scott Pelley: Because it hurts too much?

Claudia Schultz: Yes. It’s too painful to read their father’s last words.

Tina Riehm is the widow of Jeremie Riehm who had suggested a different course.

Tina Riehm: I felt relief ‘cause I was able to read it to know what happened that day. And I-- and I read it like I was with him that day, like I was standing there with him reading. So I was relieved I didn’t have to use my imagination anymore.

At 7:39 a.m., there was a building rumble. Captain Davidson yelled to his trapped crewman. “It’s time to come this way.” And the recording ends.

Frank Pusatere: The crew performed heroically, you know? And they didn’t just give up.

Frank Pusatere is the father of the chief engineer, Richard Pusatere.

Frank Pusatere: The transcript read like a suspense novel. And you were expecting or I was expecting, “Oh, it’s gonna be a happy ending,” you know? But, you know, going through it, I knew, you know, what I was reading was gonna be the end of the vessel and, you know, and the crew.

The safety board’s conclusions are expected later this year. Of the 33, not one of the crew was recovered. Their only remains are their words that tell a mariner’s story of life, and death, and the unforgiving sea.