Immunotherapy: The next frontier in cancer treatment

The effort to unlock the secret within the human immune system is already offering new hope to cancer patients for whom traditional treatments have fallen short. Dr. Jon LaPook reports. (An earlier version of this report was originally broadcast on March 12, 2017.)

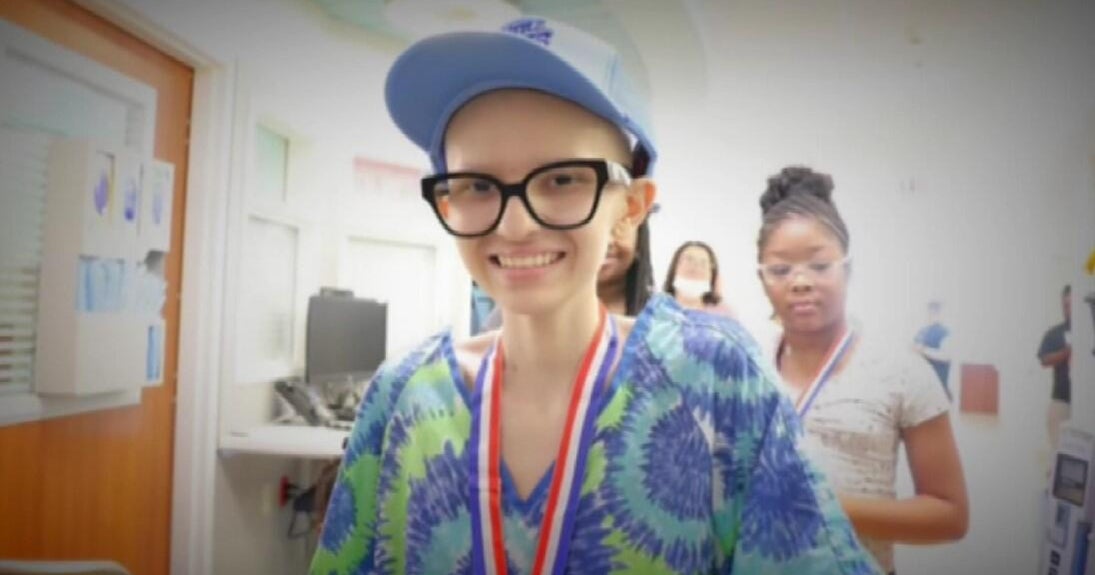

Twelve-year old Ezzy Pineda will tell you what happened to her seems like a miracle.

How is she now? "Feeling great," she told Dr. LaPook. "I feel like I could do anything."

Back when she was just nine, feeling weak and dizzy, she was taken to a hospital on Long Island, where doctors gave her a diagnosis she barely understood: leukemia.

"I'm like, 'Am I gonna die? Am I gonna live? Am I gonna be able to do the stuff I did before?'"

Ninety-eight percent of children with this form of cancer respond well to chemotherapy, so her doctors started there. But after four brutal rounds, Ezzy's cancer was getting worse.

"It was very scary," she said. "I was like, 'What did I do bad so that God could give me this punishment?'"

Desperate and out of options, Ezzy had one last chance. She was enrolled in a clinical trial at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in Manhattan for an experimental treatment called CAR-T.

After six weeks, Dr. Kevin Curran, the pediatric oncologist who treats Ezzy, couldn't find a single leukemia cell … not one. That is a patient who ten years earlier would have been told, "There's nothing we can do."

Ezzy is healthy -- just a little puffy from steroids -- because of a promising new frontier in the war on cancer: Immunotherapy, using a patient's own immune system to find and kill cancer cells.

One of the biggest challenges in fighting cancer has been that cancer cells find ways of becoming invisible to the body's defenses. And the immune system can't kill what it can't see. So doctors, in essence, taught Ezzy's immune system to "see."

They took billions of her white blood cells -- cells that normally are good at destroying invaders like bacteria and viruses, but bad at fighting cancer -- and turned them into cancer-killers.

"We can take those cells out of the body, genetically modify them, teach them how to fight cancer, and then infuse them back into the patient," Dr. Curran said.

"It's like they're bloodhounds, and you give them the scent of the cancer?"

"Exactly."

Traditional therapies like chemo and radiation often damage healthy tissue along with cancer cells. The hope is immunotherapy will be more targeted, usually sparing normal tissue. But there have been serious side-effects, even death.

"Once we knew it could work, we've been working around the clock," said Dr. Steven Rosenberg, who has been a pioneer in the field of immunotherapy at the National Cancer Institute for more than four decades. In 1984, he was the first doctor to cure a dying patient using her own immune system.

But he'll also be the first to tell you that, all these years later, immunotherapy is still in its infancy.

"We've gotten to the point now where I think we understand why the patients who are successfully treated experience tumor regression," Dr. Rosenberg said. "And based on that knowledge, I think we're going to see dramatic progress in the next few years to come."

But most patients don't have years to wait.

Like 29-year-old Burak Guvensoyler, who has a sarcoma -- a cancer in the connective tissue near his spine -- that has spread to his lungs.

Dr. Rosenberg showed LaPook scans of Guvensoyler's tumors. "These are all abnormal tumors, every one of these. He has many hundreds of different tumors that are in his lung."

Guvensoyler has already been through two rounds of chemotherapy, and multiple surgeries.

"He came to us, as do all of our patients, having exhausted what modern medicine can offer," said Dr. Rosenberg. "And our goal is not to practice today's medicine, but to create the medicine of tomorrow."

And that, he believes, would be immunotherapy.

Just as was done with Ezzy, Guvensoyler's white blood cells were "taught" in the lab to recognize his specific cancer type. A month later, he gets back his juiced-up cells -- 90 billion of them put into battle.

"You can just imagine those cells chewing up the tumor when they go in there," Dr. Rosenberg said.

"Definitely feeling very hopeful," said Guvensoyler. "I mean, to draw the lottery and actually be part of this trial is just an incredible opportunity in itself."

Now he's waiting to see if those cells did their job.

The highly-personalized treatment that patients like Guvensoyler and Ezzy received is still only available in clinical trials, but a very similar procedure will soon be FDA-approved.

And another type of immunotherapy is already available in hospitals across the country. Drugs called checkpoint inhibitors are being used to fight certain types of cancers of the kidney, bladder, lungs, and more, with especially positive results for melanoma.

While effective treatment for widespread (or metastatic) cancer remains elusive, doctors are hopeful they're at least on the right path.

Dr. LaPook asked, "Right now, in the spectrum of cancer treatment, what percentage can be addressed by immunotherapy?"

"If you look at all cancer patients, perhaps 10 percent can be helped by immunotherapy today," Dr. Rosenberg replied. "But it's getting better every day."

Guvensoylar returned to the National Cancer Institute for his first check-up since receiving his cell transfusion five weeks earlier. "I just have that comfort in terms of, like, I've done everything I can," he said.

Dr. Rosenberg went over Guvensoylar's X-rays: "We compared them to the X-rays that you had before we started the treatment. And there was, as you know, rapid growth of the tumor.

"Now, we want to see these tumors go away. But sometimes that takes time."

Sadly, time ran out in Burak Guvensoyler's fight against the cancer. He died two months later.

For now, patients like Ezzy Pineda remain the exception, but Drs. Rosenberg and Curran are hopeful, and continue to explore the boundaries of this new frontier … one previously incurable patient at a time.

Dr. LaPook asked Ezzy, "So you're lying in bed at night -- what's going through your head?"

"That the good thing is that I'm still alive," she replied. "That I could live a normal life again, that I'll be all better and probably more stronger than have been before."

For more info:

- Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York City

- Follow @sloan_kettering on Twitter and Facebook

- Immunotherapy at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

- Clinical trials by Dr. Kevin Curran

- Dr. Michael Postow, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

- Pediatric leukemias at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

- Clinical Trials at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

- National Cancer Institute's Contact Center - Patients can get in touch by phone (1-800-4-CANCER), live chat, or email to talk to an information specialist who can provide personalized responses to their questions, as well as help patients identify clinical trials across the country

- Search for clinical trials supported by the NCI

- Steven Rosenberg, CCR, NCI, Bethesda