New York schools embrace thousands of migrant children with needs beyond the classroom

This story is based on reporting for a "60 Minutes" piece that examined how New York City has been dealing with an influx of migrants bused to the city, and some of the glaring problems with the asylum system that the crisis exposed. Watch the "60 Minutes" report in the player above.

New York — Ten-year-old Cesar said his favorite part of school in the U.S. is the hot meals. While he's not a big fan of vegan Fridays, he said he enjoys the chicken and pizza served by the school.

In crisis-stricken Venezuela, Cesar said in Spanish, "there was no food, there was no money."

When he's not at P.S. 145, a public school on New York City's Upper West Side, Cesar is reluctant to eat the salads and cold meals served at a repurposed hotel in midtown Manhattan housing migrant families, according to his father, Ronny, who said the family does not have a microwave or refrigerator in their room.

Cesar's family has struggled in New York. Ronny, whose last name is being withheld because he has a pending immigration case, said he has been unable to find work, and that his wife is only working a few days a week at a fast food restaurant. They also face a years-long wait to seek asylum given a massive backlog of court cases, and their next appointment with immigration officials is scheduled for 2024.

Since the family was moved from a hotel near Central Park to one on 51st St. in midtown Manhattan, Ronny said he has struggled to pay for the subway to take Cesar to school. But he said he makes every effort to ensure his son attends school, which has offered Cesar hot meals and even a free haircut, in addition to classroom instruction.

"They're very good people," Ronny said of school officials at P.S. 145, which serves children eligible for pre-K to elementary school classes. "It's the only place where he can get basic necessities."

New York City public schools have absorbed more than 7,200 children this year who were placed in repurposed hotels or homeless shelters with their parents, according to the city's Department of Education. While the department said it does not track students' immigration status, most of the children are likely migrants who arrived in New York this year, often after being bused to Manhattan by officials in Texas.

The arrival of thousands of students who don't speak English, lack permanent legal status, live in temporary housing, need basic necessities and often have endured dangerous, traumatic journeys to reach the U.S. has posed significant operational challenges for New York City's public schools.

But despite these challenges, migrant students have been met with generosity and kindness from some educators who are helping the young newcomers and their families in ways that go far beyond their school responsibilities.

Educators at P.S. 145 have offered migrant children dual language instruction in English and Spanish, breakfast and lunch, school supplies, uniforms and after-school programs so their parents can find work, as well as free haircuts, iPads, laundry services, MetroCards and donated clothes.

Natalia Russo, the principal of P.S. 145, said her school has enrolled roughly 50 Latin American migrant children since the summer, most of them from Venezuela. Earlier this year, the school also received more than a dozen Ukrainian refugee children, who are being offered dual language instruction in English and Russian, Russo said.

"As long as they're here in my building, we will provide for them everything that we can, even if it's laundry," said Russo, a native New Yorker whose parents were born in Ecuador. "We'll do whatever it takes. Our staff will do whatever it takes."

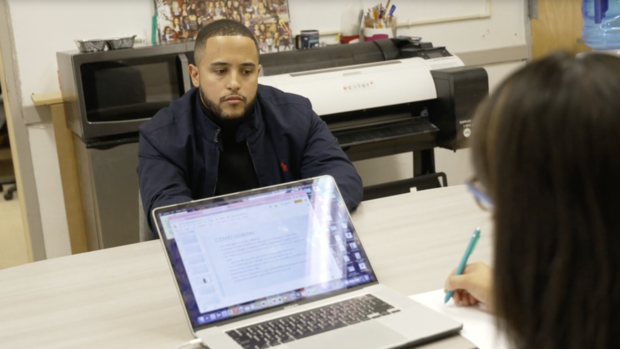

When Russo learned that migrants bused to New York were being placed in certain hotels across the city, she dispatched her school's community coordinator, Juan Abreu, to find out whether families needed help enrolling children in school. Abreu said the need was evident when he arrived at a hotel near Central Park.

"It was just a mess," Abreu recalled, noting that none of the parents he met knew how to enroll their children in school. "There was a lot of questions that I couldn't really answer at that point in time."

Abreu has also made sure that recently arrived migrant children have winter clothing, from coats and long-sleeve sweaters, to gloves and hats. He set up a system for teachers who wanted to wash migrant families' clothes, and has even helped some parents find temporary work in the city.

While Abreu noted his responsibilities technically don't go beyond enrolling children in school, he said he's committed to help them in many other ways because he identifies with them. Born in the Dominican Republic, he immigrated to the U.S. as a four-year-old. Abreu said he lived in a homeless shelter in New York City for roughly three years after his mother was the victim of domestic violence.

"When I look at the kids, I remember when I was that age," Abreu said. "And I know that I didn't have the most help. I felt like I didn't belong. And I don't want the kids to feel like they don't belong."

Since 1982, a landmark Supreme Court ruling has allowed migrant children to attend K-12 public schools in the U.S., regardless of whether they have legal status. The decision in the case, known as Plyler v. Doe, concluded that denying migrant children access to public education violated the U.S. Constitution.

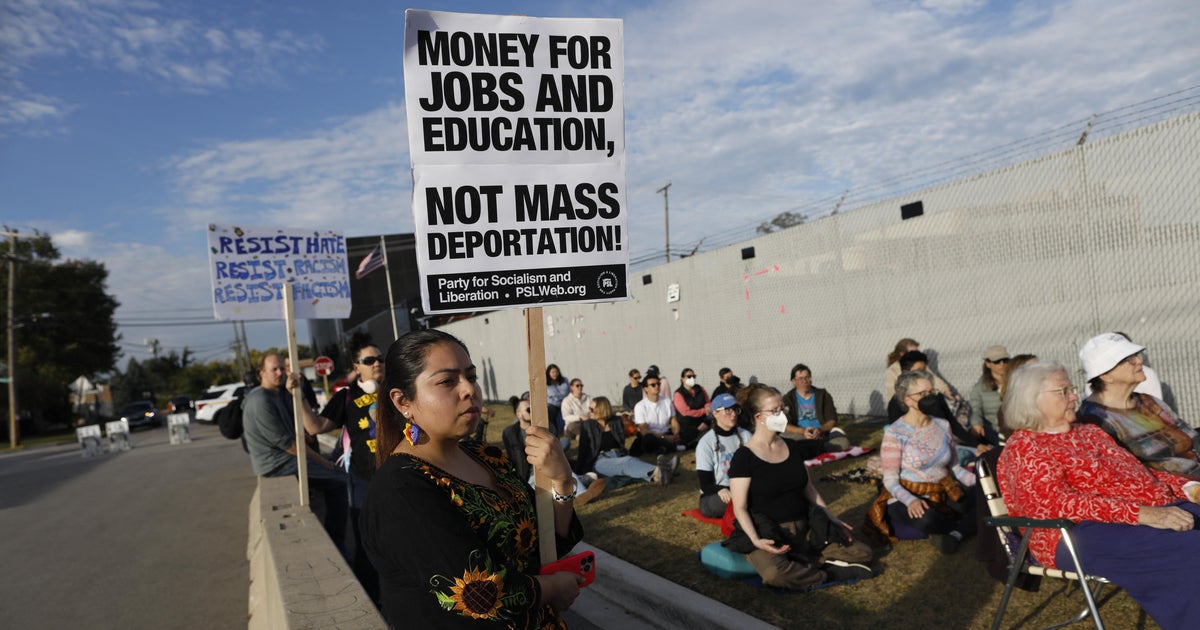

In May, Texas Republican Gov. Greg Abbott, who had been busing migrants to New York City and other Democratic-led cities to repudiate the Biden administration's border policies, suggested he would challenge the Plyler v. Doe ruling, citing "extraordinary" expenses related to educating migrant children. But Texas has yet to formally mount such a challenge.

The New York Department of Education said it could not calculate the total cost of the city's effort to accommodate migrant students, dubbed Project Open Arms, because it's a multiagency initiative. But the department said it has allocated $12 million for schools receiving migrant children.

"School counselors and social workers are working closely with the families, and our central team continue to work with superintendents and principals to deploy additional resources and support as needed," the department said in a statement. "We have been standing up additional Transitional Bilingual Programs in schools on an as needed basis, providing teachers in the languages that are most needed."

Russo, the principal of P.S. 145, said one of the "unintended consequences" of her school's efforts to help migrant children has been criticism that she and other educators are giving them preferential treatment or in some way encouraging others to migrate to the U.S. and cross the southern border unlawfully.

But Russo said she's focused on addressing the immediate needs of children and families who lack any significant support systems in the U.S.

This week, Russo is arranging a Thanksgiving dinner at a local synagogue for the families of children in her school who are living in repurposed hotels or homeless shelters. She asked school staff and community members for help purchasing decorations for the event and preparing 10 turkeys. A pro-bono lawyer, Russo added, is also reviewing the immigration cases of some families with children enrolled at P.S. 145.

Russo expressed concern about her school being able to continue assisting migrant families in the long-term without additional support. But she said ignoring their struggle is not an option.

"I don't have the legal or moral latitude to say, 'You don't belong here,'" Russo said.