America's labor shortage is actually an immigrant shortage

U.S. employers say it's a hard time to find and keep talent. Workers are decamping at near-record rates, while millions of open jobs go unfilled. One reason for this labor crunch that has largely flown beneath the radar: Immigration to the U.S. is plummeting, a shift with potentially enormous long-term implications for the job market.

In the middle of the last decade, the U.S. was adding about 1 million immigrants a year. But those numbers, which slowed down during the Trump administration, hit a brick wall when COVID-19 erupted in 2020.

"This decline reflects both tougher immigration policies and the pandemic which reduced legal immigration and caused some recent immigrants to return to their native countries," David Kelly, chief global strategist at JPMorgan Funds, said in a recent report.

After COVID-19, most travel shut down. Immigration processing stopped, and many foreign workers returned to their home countries. In 2020, immigration fell to half of its 2016 level; last year, it fell to just over a quarter.

2 million people short

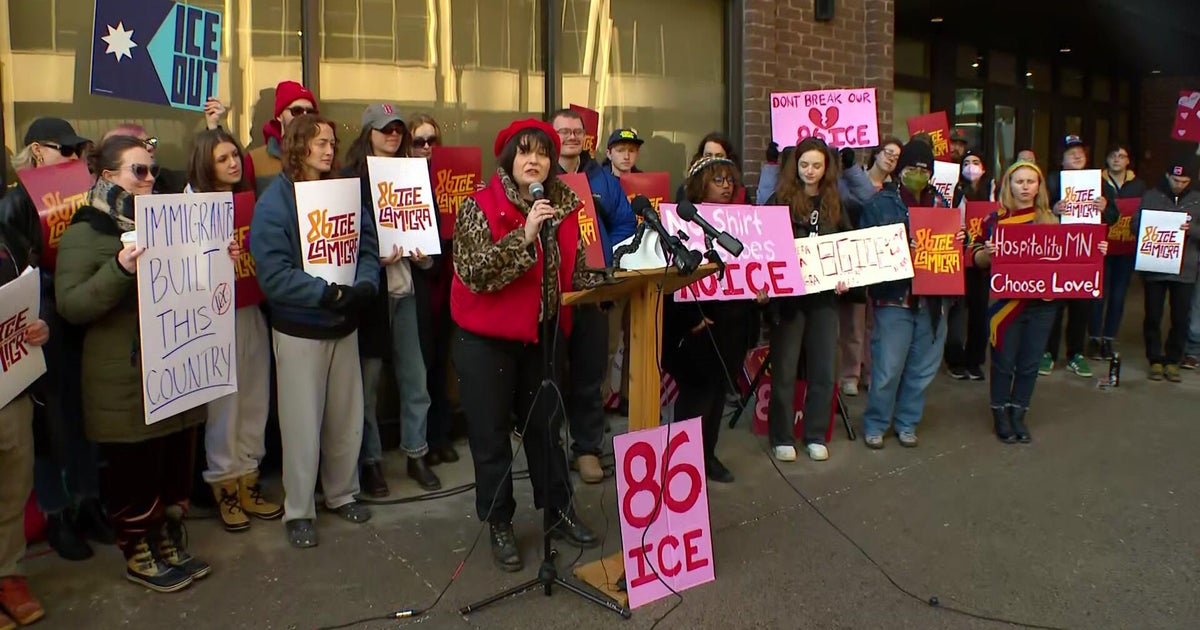

By one calculation, the U.S. workforce today has 2 million fewer immigrants than it would have if immigration had continued at pre-pandemic levels. That gap is especially being felt in low-paying industries, such as leisure and hospitality, food services retail, and health care.

"Sectors that are especially reliant on immigrant workers had significantly higher rates of unfilled jobs in 2021," economists Giovanni Peri and Reem Zaiour of the University of California, Davis, wrote recently.

Immigrants are especially crucial in health care, where they make up a disproportionate share of workers. One in five nurses, one in four health aides, and nearly one in two housekeepers and gardeners is an immigrant, according to research coauthored by Williams College economic professor Tara Watson.

The immigration drop coincides with other demographic trends that are squeezing the workforce. Americans are retiring in droves as baby boomers, the largest generation of workers, reaches retirement age — a longstanding demographic shift that sped up during the pandemic.

The past year has seen the slowest population growth since America was founded, and a major reason is the immigration decline. U.S. birth rates have been falling for years, to the point where immigration has been the chief driver of population increase.

But the current low levels of immigration are unlikely to reverse quickly given the ongoing pandemic and backlogs in the U.S. immigration system that have millions waiting for a visa or green card.

In the short term, that's good news for existing workers and bad news for employers. Since the supply of workers is more or less tapped out, "the labor market should remain very tight by historical standards," JPMorgan's Kelly wrote. "[F]urther strong gains in wages are likely as those companies that can most profitably employ workers bid up their compensation."

In the longer term, the picture is mixed. With workers scarce and labor costs rising, businesses will look to automate more jobs, Kelly said. And because the U.S. economy as a whole depends on population growth, there are real doubts about what will happen when there are too few young workers to support aging ones.

The "financial health of Social Security and Medicare, as well as capacity for caregiving of the elderly, will be strained without continued positive growth in the U.S. population," Watson, of Williams College, wrote recently.

A dearth of immigrants could also mean a less dynamic job market overall. Not only do immigrants tend to be younger than the U.S. population overall, they are more likely to work and three times as likely to start businesses, by one estimate.