Migrant families face starkly different fortunes under inconsistent border policy

McAllen, Texas — Dania said her 5-year-old son, Wilfredo Jr., clamored for food and water during their trek to the U.S.-Mexico border. But she said both were scarce.

"As a mother, you suffer from seeing your child like that," Dania told CBS News in Spanish.

Wilfredo, Dania's husband, said the fear of returning to Nicaragua helped them overcome the trials of the journey.

"We knew what we experienced in Nicaragua and that our family could be in danger if we returned there," Wilfredo said, noting that he opposed the Nicaraguan government. "So, you risk more, with the hope of finding safety for your family here in the U.S."

After crossing the Rio Grande, the family was taken into U.S. Border Patrol custody. Instead of turning them back to Mexico, U.S. officials released the family, who were tested for COVID-19 by volunteers in south Texas. After testing positive, Dania and her family were isolated for a week in a hotel.

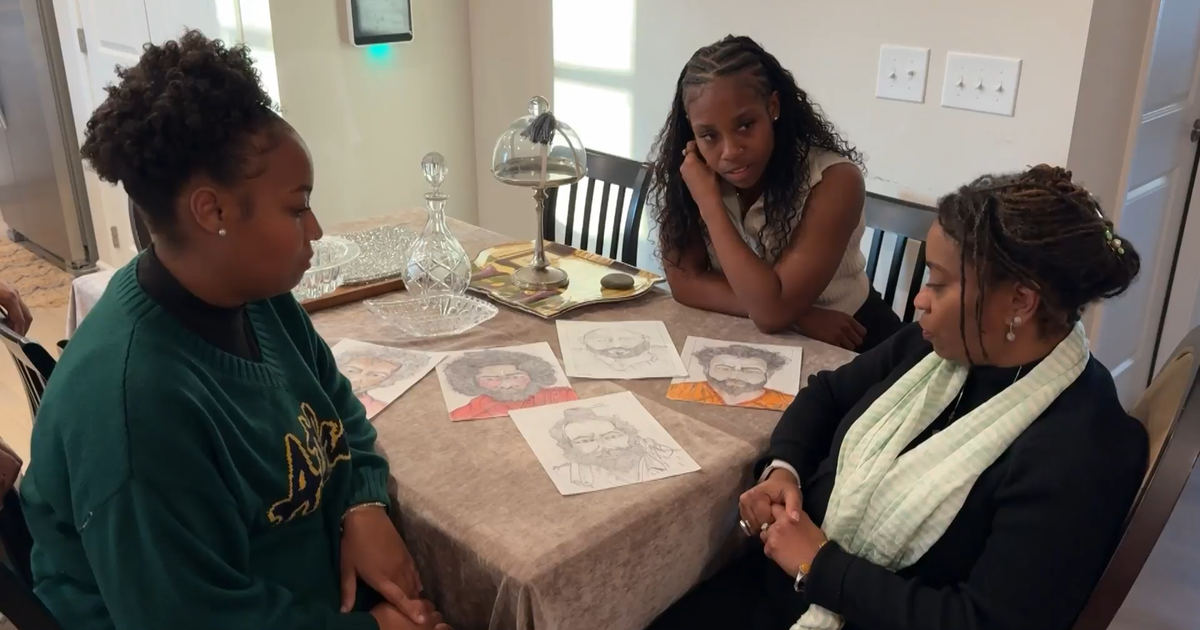

Once Dania recovered, the family was transported to the Humanitarian Respite Center, a shelter in McAllen operated by Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley. Dania and Wilfredo said they are grateful the U.S. government allowed them to pursue an asylum case, noting their child feels safe.

"I felt his happiness the moment he came," Dania said of Wilfredo Jr.

However, not all migrant families crossing the southern border are being allowed to seek U.S. refuge. The Biden administration has continued to use a public health authority first invoked under former President Donald Trump to rapidly expel tens of thousands of migrants, including parents and children traveling as families, to Mexico or their home countries.

Rosa, a mother from Honduras, said she and her 6-year-old son crossed into the U.S. near the Mexican city of Reynosa. They were processed under a bridge and then detained for four days in a Border Patrol station, where she said her child became sick. She thought her detention was a sign that she and her son would be allowed to stay in the U.S. to reunite with her brother in Louisiana.

Rosa said she told U.S. border officials that she and her child fled Honduras after her father, a police officer, was killed and the family was threatened. Rosa said she also told them she and her son had been kidnapped in Mexico during their trek to the U.S. border.

However, Rosa was not allowed to start an asylum case. She and her son were instead flown to San Diego, where U.S. authorities expelled them to Tijuana, Mexico.

"When I saw we were taken to Mexico, I had the worst feeling," Rosa, who is now staying at a shelter in Tijuana, told CBS News in Spanish. "All the bad things that I thought had ended could suddenly happen again. We have a lot of fear."

Last month, the advocacy groups Human Rights First, the Haitian Bridge Alliance and Al Otro Lado compiled 492 reports of assault, rape and kidnappings against asylum-seekers and migrants in Mexico who were affected by the Title 42 expulsions during the Biden administration.

Department of Homeland Security (DHS) officials have said they would like to expel most migrants, including families, under Title 42, the emergency public health authority. But they've said Mexican officials in the state of Tamaulipas have refused to accept Central American families with young children, forcing U.S. authorities to release some families in south Texas.

The inconsistent and seemingly arbitrary enforcement of the Title 42 policy has sown confusion at the U.S.-Mexico border, lawyers and migrants said. Some families are swiftly expelled without due process while others are allowed to stay in the U.S. because of where they entered, the age of their children or sheer luck.

Some families who are encountered in south Texas, including those with young children like Rosa and her son, are being detained by Border Patrol officials for days before being flown hundreds of miles across the southern border just to be turned back to Mexico from El Paso and San Diego.

Advocates for asylum-seekers have denounced these flights, saying they undermine the stated public health justification behind Title 42 rule. The Biden administration, like the Trump administration, has argued the rule is necessary to curb the spread of COVID-19 inside migrant holding facilities and protect border officials from the virus.

During a call with reporters on Sunday, Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas acknowledged the ongoing flights in the Rio Grande Valley.

"There are some families who cannot be expelled in that particular area of the southwest border, by reason of the capacity constraints in Mexico and the Mexican area of Tamaulipas," Mayorkas said. "And so in fact families are being moved to a different part of the border and, in the furtherance of the public health imperative, are being expelled there."

Asked by CBS News whether the practice of flying families from south Texas to other parts of the southern border undermines the public health reasoning behind Title 42, Mayorkas said his department is "taking a close look" at the flights.

Logistical issues are not the only reason some families are being allowed to seek U.S. asylum. The Biden administration has been permitting some parents and children identified as vulnerable by advocacy groups to enter official ports of entry under humanitarian exceptions to the Title 42 process.

Lee Gelernt, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union, said his group has been sending a daily list of 35 vulnerable families and individuals stranded in Mexico to the Biden administration so they can be admitted and allowed to continue their cases in the U.S.

"We are pleased some families will be allowed to enter and escape danger, but this is by no means a substitute for ending Title 42," said Gelernt, who is currently leading a lawsuit against the expulsions of families.

A DHS spokesperson confirmed the department is working to "streamline a system for identifying and lawfully processing particularly vulnerable individuals who warrant humanitarian exceptions" to the Title 42 expulsions.

"This humanitarian exception process involves close coordination with international and non-governmental organizations in Mexico and COVID-19 testing before those identified through this process are allowed to enter the country," the spokesperson added.

Sister Norma Pimentel, who runs the Humanitarian Respite Center in McAllen as the executive director of Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley, said she has been receiving fewer families from U.S. border officials in recent weeks, compared to earlier in the spring. She said that is likely due to U.S. authorities expelling more families to Mexico, including by flying them to other parts of the border.

Pimentel expressed concern about the continued expulsions of families.

"The conditions in Mexico are terrible," she told CBS News. "And so when we as a country, we turn back these families, whether it's Title 42 to or because of children under the age of six now being sent back, all of them are in great danger when they're sent back."