Detention facilities for migrant families near empty as crowds left at bus stations and shelters

In recent weeks, bus stations along Texas' Southern border have been crowded with migrant families, deposited at the transportation hubs by border agents who say the immigration enforcement system is so overwhelmed they're left with no other choice.

But on April 8, at the nation's largest detention center for immigrant families in Dilley, Texas, nearly 80 percent of the beds were unfilled. The facility, which can fit as many as 2,400 people, was housing just 499, according to a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement spokesperson.

Nationally, there are more than 3,200 beds devoted to families in three facilities. The nation's second largest such facility, in Karnes, Texas, was temporarily converted this month to house adult women apprehended without families. The smallest facility, in Leesport, Pa., currently has nine people, just under 10 percent of its capacity.

A spokesperson for ICE confirmed to CBS News that the numbers are unusual, and said a surge in migrants at the border had overwhelmed the government's ability to transport families to detention centers.

"These numbers are low, which has a lot to do with the current influx of family units' impact on our transportation resources," the spokesperson said. More than 53,000 people traveling as part of family units were apprehended in March near the southwest border, according to Customs and Border Protection statistics. Many are being transported by CBP to bus stations or shelters. They're released "with a notice to appear before an immigration judge," said Brian Hastings, chief of law enforcement operations for CBP, during an April 10 press briefing.

Attorneys and immigration activists question ICE's explanation for the nearly empty facility in Dilley.

"The whole thing is really confusing," said Erica Schommer, a clinical associate professor of law with the St. Mary's University Immigration and Human Rights Clinic. "I don't understand how for years they were capable of doing it, and now they can't. If they transported people from just the Rio Grande Valley to Dilley, they could fill it. I'm not advocating for them to do that — but the explanation just doesn't make sense to me."

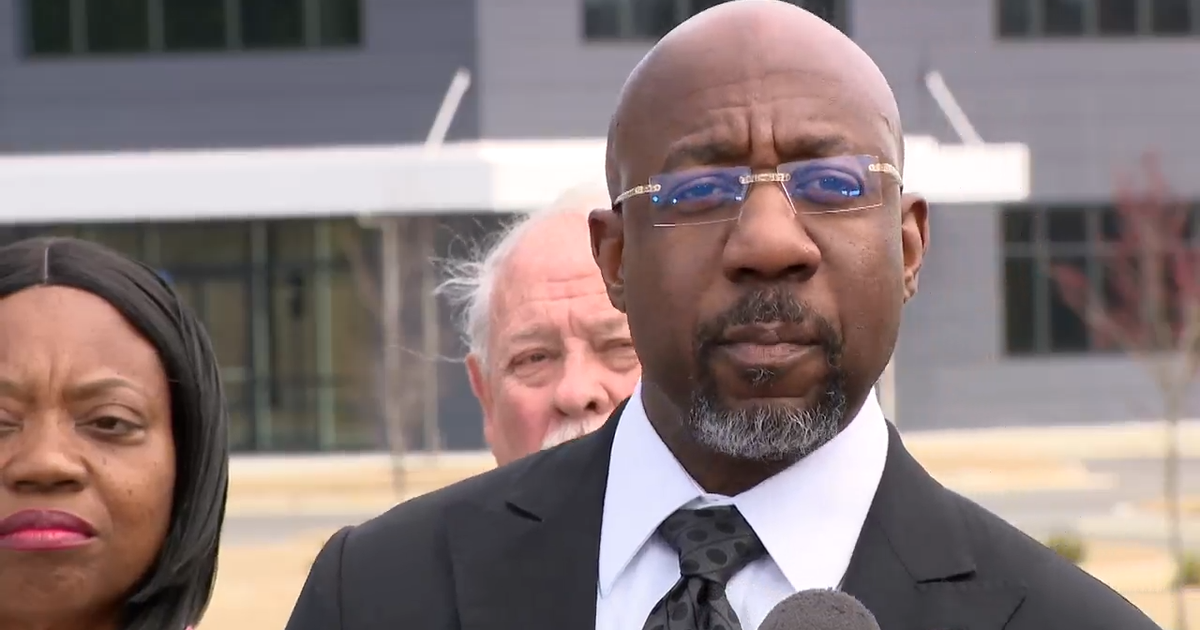

The explanation also doesn't sit well with Peter Schey, a California attorney involved with monitoring the Dilley and Karnes facilities as part of the landmark Flores v. Reno case. A settlement from the case set the rules for how immigrant children, and ultimately families, can be detained in the United States.

"For several years, they have detained several thousand people (at a time), at a cost of over $100 million," Schey said in a text message to CBS News.

Both Schey and Schommer said they suspect the imagery of crowds of families at shelters and bus stations fits better with the administration's message that there's a national emergency at the border.

Even so, they say prompt release is a preferable option to more detention — and the one called for in the Flores Settlement.

"Normally just being released and not having to go to detention is the best thing for families. There's lots of evidence from psychologists and researchers that being put into detention has a detrimental effect on children," Schommer said.