Idaho man who didn't match DNA from killing is freed

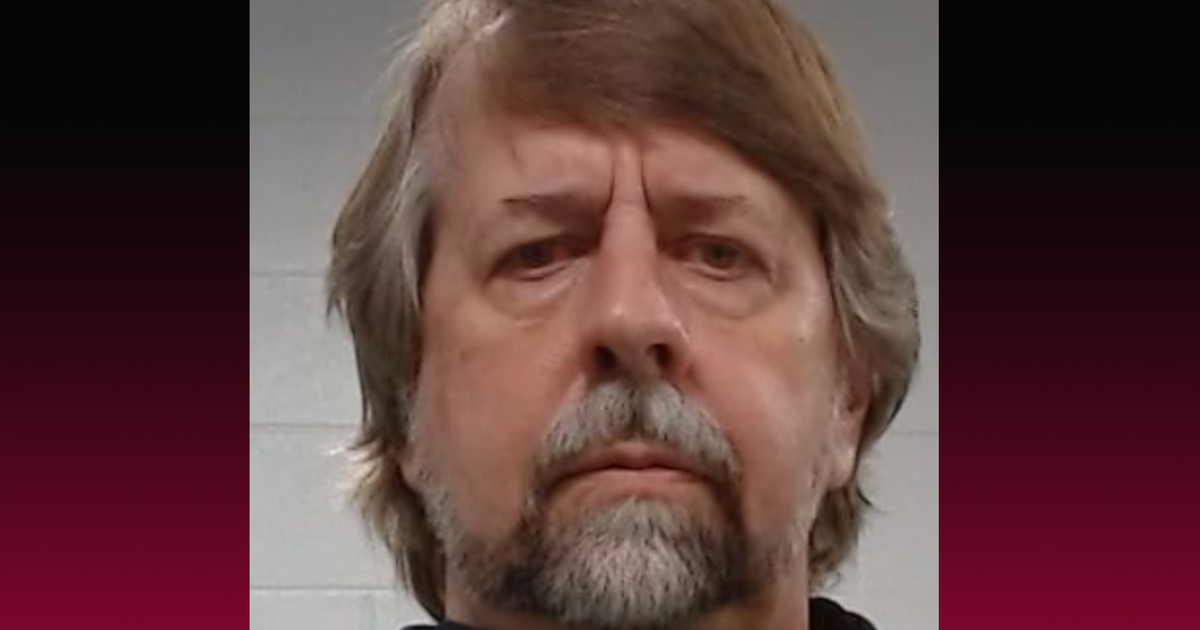

BOISE, Idaho - An Idaho man who experts say was coerced into a false murder confession was freed Wednesday after spending half of his life behind bars.

A judge released Christopher Tapp after vacating his rape conviction and resentencing him to time served for the 1996 killing of Angie Dodd.

The release came after years of work by Tapp’s attorney, public defender John Thomas, and advocates, including Judges for Justice, the Idaho Innocence Project and the victim’s mother, Carol Dodge.

Angie Dodge was 18 and living in an Idaho Falls apartment on June 13, 1996, when she was sexually assaulted and killed at her home.

Tapp was a 20-year-old high school dropout at the time. He was interrogated for hours and subjected to multiple lie detector tests by police before confessing, but DNA evidence taken from the scene didn’t match Tapp or any of other suspects in the case.

The release doesn’t exonerate Tapp — his murder conviction still stands under the plea agreement that transformed his 30-years-to-life sentence to time served. But the agreement allowed Tapp to leave the courtroom as a free man after spending 20 years in prison. He otherwise wouldn’t have been able to seek parole until 2027.

“Chris Tapp is innocent,” his attorney, Thomas, told the Post Register newspaper Tuesday. Still, Thomas said, the plea deal was the right decision because it came with the certainty of freedom.

In court Wednesday, Carol Dodge said she was overwhelmed and felt great sadness that Tapp had lost 20 years of his life to prison, television station KIDK reported. She said she hoped people would continue to seek justice for her daughter by finding the real killer.

The Idaho Falls Police Department announced Wednesday that it has a sketch of a suspect in the case. However, police did not release it or immediately return calls from The Associated Press inquiring how it was obtained.

Most of the recent developments in the case have focused on DNA found at the scene.

Dodge’s body was found by co-workers who went to check on her. She had been raped and stabbed. Investigators were able to obtain DNA samples from hair, skin cells and body fluids at the scene.

The initial investigation spanned several months, and by the start of 1997, detectives began to suspect that Benjamin Hobbs and Tapp may have been involved. Hobbs was arrested in Ely, Nevada, in connection with a rape and accused of using a knife during the crime. Tapp, who was friends with Hobbs, was arrested in January and questioned about Hobbs’ suspected involvement in Dodge’s killing.

Over the next few weeks, Tapp was interrogated nine times and subjected to seven polygraph tests. At various times, police officers suggested he could face the death penalty, told him that he was failing the lie detector tests, suggested he may have repressed memories of the killing and offered him immunity if he implicated Hobbs and another suspect. He eventually confessed to being involved in the death.

But none of the DNA found at the crime scene matched Tapp, Hobbs or the other suspect. It all belonged to the same unknown man, according to the analysis.

Prosecutors, seemingly unaware of the nature of some of the police contact with Tapp, accused him of lying and rescinded his plea deal. Tapp was convicted after his recorded confession was played for the jury.

Over the years, advocacy groups for the wrongfully convicted began fighting for Tapp’s exoneration. His attorney tried to get the conviction overturned, but was stymied by Idaho’s strict one-year statute of limitations for some post-conviction proceedings and a limited court record.

Former FBI agent Gregg McCrary later reviewed the videotaped interrogations and polygraphs at the request of Judges for Justice.

“While the investigators should be commended for engaging in the best practice of recording virtually all of their contact with Mr. Tapp, they also became ensnared in a host of cognitive biases,” McCrary wrote to Bonneville County Prosecuting Attorney Bruce Pickett in 2014.

A polygraph expert recruited by the group, Boise State University professor Dr. Charles Honts, said the polygraphs were used “as a psychological rubber hose in an effort to coerce a confession.”

Under the plea deal, Tapp can’t continue legal efforts to get his conviction overturned and must pay into Idaho’s victim compensation fund.