NOAA hurricane forecast warns of a very active season ahead

With just over a week to go before the official start of hurricane season, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is warning of a very active season to come. The agency said most of the factors considered in preparing the seasonal forecast are pointing to a season of many storms and intense storms.

"NOAA's analysis of current and seasonal atmospheric conditions reveals a recipe for an active Atlantic hurricane season this year," said Dr. Neil Jacobs, acting NOAA administrator.

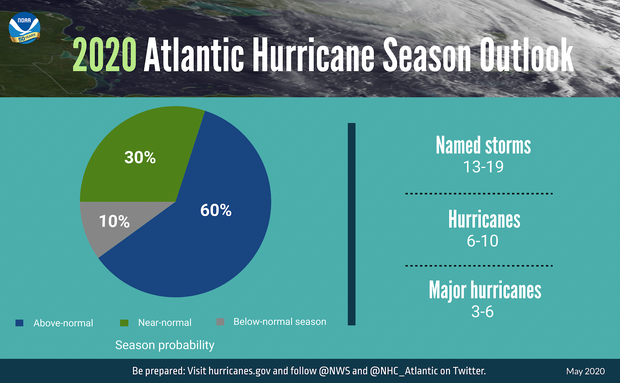

The forecast from NOAA's Climate Prediction Center calls for a 60% chance of 13 to 19 named storms (normal is 12). Six to 10 of those could become hurricanes (normal is six) and three to six major hurricanes are forecast (normal is three). A storm qualifies for a name when maximum sustained winds surpass 38 mph; a hurricane has winds of greater than 73 mph, and a major hurricane has winds greater than 110 mph.

This forecast is in line with other seasonal forecasting groups which have also warned of an usually active 2020 hurricane season.

NOAA says that a combination of several climate factors is driving the strong likelihood for above-normal activity in the Atlantic this year. The factors considered include El Niño-La Niña conditions, Atlantic sea surface temperatures, strength of the trade winds in the tropical Atlantic, strength of wind shear in the upper atmosphere, and the state of the West African monsoon season.

El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) conditions in the tropical Pacific Ocean are expected to either remain neutral or to trend toward La Niña, meaning there will not be an El Niño present. The warm water produced in the equatorial Pacific Ocean during El Niño years usually favors active weather in the Pacific and overwhelms the Atlantic Basin. Therefore El Niños typically suppress hurricane activity in the Atlantic, and this summer's lack of El Niño would typically correspond to an active Atlantic Basin.

If a La Niña forms — meaning cooler tropical Pacific waters — then the Atlantic hurricane season may go even further into overdrive. As of this week, more signs of La Niña are beginning to emerge.

So far this spring, there have been warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures in most of the tropical Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea. If that endures into the height of the hurricane season — August through October — then hurricanes will have more fuel to feed off of.

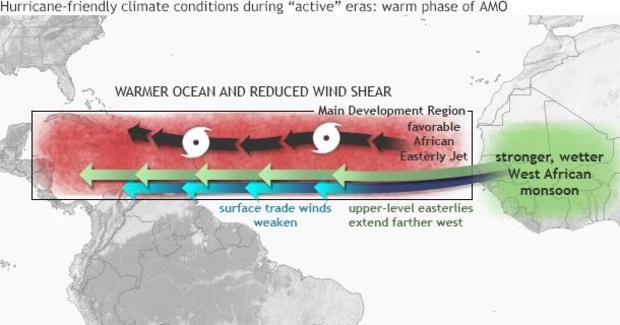

NOAA also anticipates reduced vertical wind shear. This means that upper level winds are likely to be weaker and more uniform than normal in the tropical Atlantic, providing a more nurturing environment for growing storm systems.

Along with weaker upper level shear, there should also be weaker tropical Atlantic easterly trade winds. This allows for better structure in thunderstorm development inside of aspiring systems, by allowing for systems to more easily organize and spin.

Lastly, NOAA points to an enhanced West African monsoon in which more clusters of thunderstorms — or seedlings — emerge off of Africa into the warm eastern tropical Atlantic waters. With the supportive water temperatures and environmental winds expected, each seedling has a better chance of growing into a bonafide tropical system.

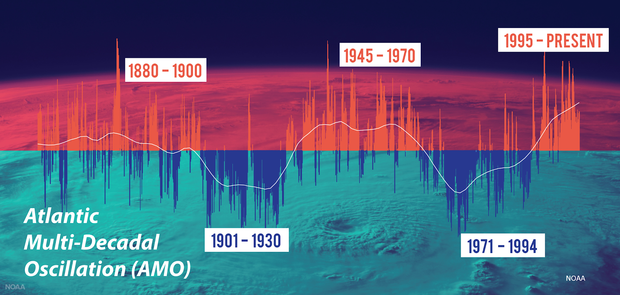

In its news release, NOAA discussed similarities in this upcoming season to other very active Atlantic hurricane seasons since 1995. That was when the Atlantic Ocean entered an active phase of what's called the Atlantic Multi-Decadal Oscillation (AMO). "Similar conditions have been producing more active seasons since the current high-activity era began in 1995," NOAA said.

The Atlantic Multi-Decadal Oscillation is a 20- to 30-year cycle of colder and warmer than normal Atlantic sea surface temperatures. Consistent with warmer phases of the AMO, Atlantic high-activity eras have occurred from 1880 to 1900, 1945 to 1970, and 1995 to the present.

As seen in the below image, warm cycles shown in red correspond to hurricane activity spikes in the Atlantic, with an increase in the frequency and intensity of hurricanes.

Since 1995, most seasons have featured above-normal hurricane activity in the Atlantic, with many more major storms than normal. For instance, 2005 was the most active hurricane season, with a record-breaking 27 named storms and 15 hurricanes.

But this uptick is not solely due to natural swings in activity. A study released earlier this week, led by NOAA hurricane researcher James Kossin, finds a significant global trend in the increase of tropical system intensity over the past four decades, indicating that manmade global warming is leading to stronger hurricanes.

To reach this conclusion, the team analyzed satellite images of tropical systems dating back to 1979. They concluded that warming has increased the likelihood of a hurricane developing into a Category 3 or higher by 8% per decade. Since the trend is global — not just confined to one ocean basin — natural, regional climate fluctuations alone can not explain the increase.

In fact, since 2016 alone, six very memorable Category 5 hurricanes have formed in the Atlantic basin. They included Hurricane Dorian, which decimated the northern Bahamas last year, and in 2017 Hurricanes Irma and Maria left Caribbean islands in ruins.

Six Category 5 systems in just four years' time is an unusually high number, considering that since the satellite era began in the 1960s there have only been 26 Category 5 storms in the Atlantic.

And it's not just the Atlantic. In 2015, Hurricane Patricia became the strongest storm on record in the northeast Pacific, with sustained winds of 215 mph. And in 2013, Super Typhoon Haiyan broke records as the strongest system in the northwest Pacific, with winds of 195 mph. Just this week, Super Cyclone Amphan became one of the strongest storms on record in the Bay of Bengal, with winds over 165 mph.

In NOAA's Thursday morning conference call to announce the seasonal outlook to members of the media, Jacobs was joined by Wilbur Ross, the U.S. Secretary of Commerce, who oversees the agency. Ross warned of the busy season ahead, while also touting NOAA technology to help with storm forecasting and warnings.

NOAA noted that this summer the agency plans to upgrade the hurricane-specific Hurricane Weather Research and Forecast system (HWRF) and the Hurricanes in a Multi-scale Ocean coupled Non-hydrostatic model (HMON) models. The HWRF will incorporate new data from satellites and radar from NOAA's coastal Doppler data network to help produce better forecasts of hurricane track and intensity during the critical watch and warning time frame.

NOAA will also begin feeding tropical region temperature, pressure and humidity data from the COSMIC-2 satellites into weather models to help track hurricane intensity and boost forecast accuracy. In addition, NOAA and the U.S. Navy will deploy a fleet of autonomous diving hurricane gliders to observe conditions in the tropical Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea in areas where hurricanes have historically traveled and intensified.

With the busy season forecast, and the country still dealing with the major disruptions of the coronavirus pandemic, Jacobs warned, "Now is the time to ensure you have a plan in place." Agency officials hope that these technological advances will ensure that Americans have the critical warning time needed before a storm hits.