Rebuilding in Florida's Keys, at what cost?

Like pioneers in a wagon train, a long line of homeowners has crossed the bridges back down to the Florida Keys, determined to reclaim their homes from the ravages of Hurricane Irma. For most, optimism is riding along.

Seeing their wrecked homes is their first dose of reality; the next will be trying to rebuild. They'll face huge expenses, government regulations that are growing ever more stringent and an often-lengthy process of negotiation with their insurance company to decipher a clause-laden contract that doesn't always provide what they thought it would.

That's the easy part. Some people are advocating for the opposite, arguing that many homes on these low-lying "barrier islands" -- built by nature to absorb a hurricane's punch and not to pass it along to the mainland -- shouldn't be resurrected.

"People and communities should think hard about whether to rebuild -- and where -- before they even get to the 'how,'" said Vice President Steve Ellis of Taxpayers for Common Sense, a nonprofit Washington, D.C.-based budget watchdog group.

He's not the only one. "We should seriously consider that there are some locations in the Florida Keys which can't be built on at all," said Robert Hartwig, co-director of the Center for Risk and Uncertainty Management at the University of South Carolina. "Without long-term thinking, the Keys don't have a future. They'll be wiped out regularly."

With catastrophic Hurricane Maria slamming Puerto Rico and now headed somewhere up the Atlantic Coast, that may seem obvious. But people tend to have short memories. So the lessons learned from the last series of major hurricanes -- Katrina, Rita and Wilma in 2005 -- may need to be relearned as mother nature butts heads with human nature. Just earlier this year, a group of Florida Keys business leaders led the charge against any increase in their insurance "windstorm rates," claiming they weren't "actuarially sound."

Indeed, most Floridians will try to rebuild their homes and businesses as soon as possible. But when they do, they'll come face to face with the economic necessity of finding the money, the challenge of doing it and finally -- and possibly the biggest hurdle -- purchasing insurance all over again.

This is what awaits those looking to rebuild. They'll realize that their insurance won't cover everything. Virtually every policy written in Florida includes a "hurricane deduction" of 2 percent to 5 percent. In essence, if the home you lost is valued at $400,000, you could pocket only $380,000.

Some insurers didn't even offer insurance for windstorm damage from Irma, transferring that risk to state-run insurer Citizens Property. Homeowners without that Citizens policy and who relied on traditional insurers for this type of coverage, could be in for a surprise.

The same is true for flood insurance, almost always a separate policy. Even though Irma was a 135-mile-per-hour windstorm hurricane, flooding was also a major issue. One estimate is that less than half of Florida's homeowners had such coverage.

This will cause a lot of wrangling for coastal property owners, where "storm surge" -- waves and tides driven onshore by winds -- caused a lot of damage. Insurers will pay for a portion of that, but they'll argue about the rest, just as they did after Hurricane Katrina in 2005 by claiming that simple water damage isn't covered.

Those who do have coverage may find that it can take years to resolve claims, particularly when insurance adjusters and engineers minimize the damage, as they did after Superstorm Sandy in 2012. Many homes destroyed by Sandy are still in the process of being restored, partially because the banks that hold the mortgages on these properties are reluctant to release any money until they have actual repair contracts in hand.

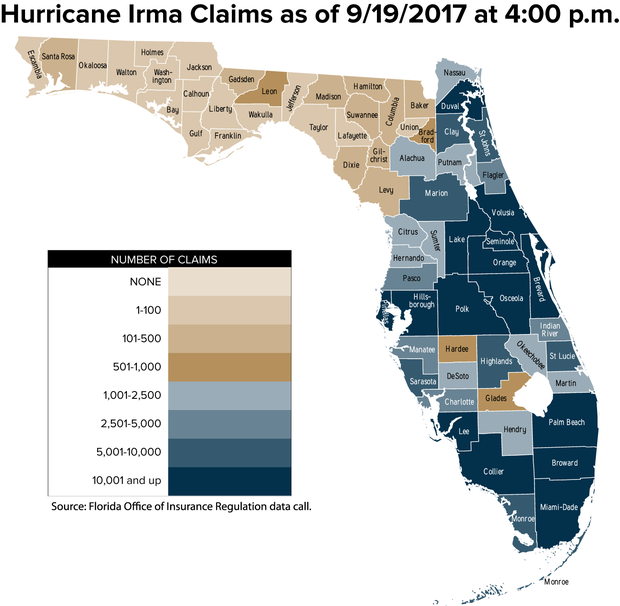

Thus far less than 7 percent of Floridian homeowners' claims have been closed and far fewer commercial and mobile home claims, according to the Florida Office of Insurance Regulation.

But getting the money is only the start of the rebuilding process. How to spend it and whether there's enough of it comes next. Florida has some of the strictest building codes in the nation. As a bicoastal state, it's always susceptible to a double punch from hurricanes. These building codes, which were passed statewide in 2002, apply to structures built thereafter. Florida building inspectors will likely insist that homes being rebuilt have to meet these codes.

It's not going to be cheap. One estimate by builders is that regulatory compliance could add almost 50 percent to the cost of rebuilding, well beyond the likely insurance settlement. That could go even higher for the Florida Keys, where everything, including labor and construction materials, has to be brought in on the only highway.

In combination with this year's other hurricane disasters (so far), Harvey and Maria, the cost of labor, plywood and conduit cable is likely to soar. Chief Executive Julie Rochman of the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS), which researches ways to protect buildings against natural disasters, pegged the cost of construction in Florida's Pinellas County, which includes St. Petersburg and barrier islands, at $200 to $250 per square foot. That figure was computed before Hurricane Irma. And the average American home is now 2,600 square feet.

Many communities, as well as the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) itself -- which is picking up the tab for much of the cost of these hurricanes -- are likely to insist that reconstructed homes be raised on pilings to help prevent future flooding. This will require heavy construction crews and cranes.

Even partial repairs, such as shatter-resistant windows and storm shutters, can be expensive. For a full house or roof rebuild, better nails and tape could add 5 percent to the total cost, said the IBHS.

When the house is rebuilt, the homeowner will still have to purchase insurance. And that won't be cheap, either. Property insurance in the Keys currently averages about $4,000 per year. Florida Gov. Rick Scott has declared a 90-day "freeze" on any increase in insurance rates, but the freeze isn't binding on the several insurers that have already requested rate increases, which range as high as 10 percent.

Many homeowners are likely to buy their coverage from state-run insurer Citizens Property, which by law can increase rates only by 10 percent a year. But Citizens, which already raised rates this year due to an inflated number of legal cases against it, can also charge an "assessment" to all types of Florida property owners, according to Hartwig of the Center for Risk and Uncertainty Management.

So will insurance rates rise? Almost certainly, and what may be worse, payouts will fall. Consumer advocates have long complained about the clauses inserted into new contracts, such as the "hurricane deductible." And now these clause are likely to become more common even as the deductibles rise.

Because flood insurance rates are set so low, the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) has lost billions of dollars for years, which could prompt Congress to turn some of the program over to private insurers. If this happens, consumer advocates say the cost of coastal flood insurance will skyrocket.

States devastated by these 2017 hurricanes will ask for and get at least $100 billion in federal aid, predicted Hartwig. But it will have to be shared by Florida, Texas and Puerto Rico.

And then there's the question of who gets the money? Does it go to remediation, such as repairing the current storm damage, or to mitigation, making sure the next one doesn't do as much damage.

For people like Hartwig and Ellis, the answer is clear: It makes more sense to build seawalls, fortified pumping stations and tear down buildings that stand in the way of the inevitable tide rather than fix them again afterward. "Every dollar of mitigation saves you $6 in the long run," argued Hartwig.

But homeowners, businesses and builders in the Keys would certainly see it differently. And they have a lot of clout, at least for now.

"Hurricanes are great teachers, but our ability to retain these lessons is spotty," said Lynne McChristian, a professor of insurance at Florida State University. "It seems that every 12 years or so we need a refresher course."