Hurricane Harvey: A fluke or the future?

Like rounds of artillery, hurricanes are coming in a salvo the likes of which we haven't seen in more than a decade. Maria, which devastated Puerto Rico this past week, was the first Category Four to make a direct hit on the island in 85 years. Last month, Hurricane Harvey was the most ferocious rainstorm ever recorded in the continental U.S. The number of storms is higher than usual but its their intensity that is extremely rare with two Category Fours and two Category Fives making landfall in a month. The question facing America's coastal cities is this: Is the ferocity of these storms a fluke or the future?

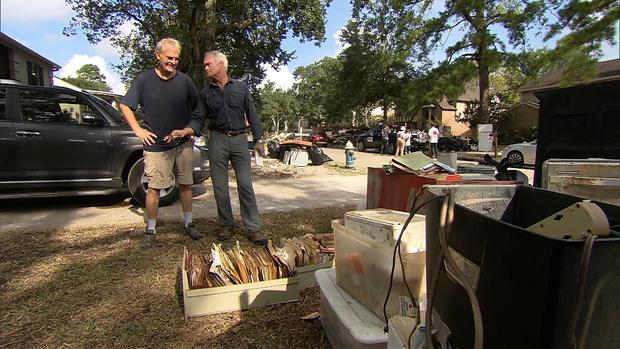

No one died on Bramblewood Drive, but lives were lost, the lives we measure in memories: the bike that taught the kids how to fly, the perfect dining room chairs, the letter jacket they can't believe they saved all these years.

14831 Bramblewood in West Houston is the Shields' place. Vince Shields rolled his family history to the curb and dumped decade after decade.

Vince Shields: My wife's a seamstress. And so these are probably her patterns she had through high school and on up. We lost a lot of personal pictures, but most of this, I won't have to have a garage sale.

Shields, who retired from Shell, has lived on Bramblewood 16 years.

Vince Shields: Here's the waterline, so I'm 6-2.

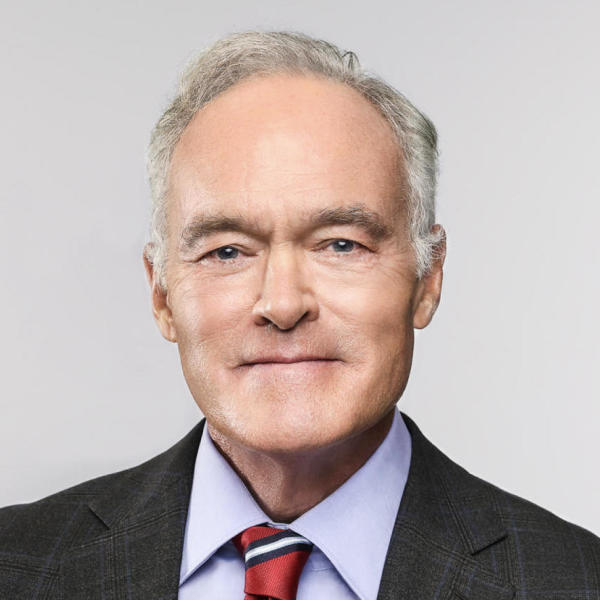

Scott Pelley: And the waterline is as tall as you are, 6-foot-2.

He'd never seen water in the house. The flood started to drop after two feet, but it surged to six after engineers opened the gates on two antiquated flood control reservoirs to stop the dams from failing.

Vince Shields: We've had church crews in here. Second Baptist, we go to Second Baptist, they had a crew out here. We've had a couple of Christian crews from Lafayette.

Scott Pelley: That's how you got all this done, all volunteers. People just walked up and knocked on the door.

Vince Shields: Yeah, or you sign up at church and put your name on the list and people show up, its amazing. God works.

More than 80 people were killed. And around Houston, it's estimated that 27,000 homes were destroyed. Almost 25 percent of Houstonians live below the poverty level. And many of their homes were in the flood plain.

Michelle Seage: This is Joe's house, you'll see him – he's in the black shirt, if you have any questions ask me or ask Joe for exactly what he wants us to do.

Next door to Vince Shields, Joe Kilchrist's place was being gutted by military vets. Kilchrist kept the plywood from the last big storm season back in '05. The vets call themselves Team Rubicon.

Michelle Seage: Your masks have to stay on. You do not want to breathe in fiberglass.

Michelle Seage says they'll have 2,000 volunteers from all over the nation for two months.

Michelle Seage: So yesterday I had a whole street, all the debris piles were beautiful and neat and ready for the city. And then I get assigned here this week and you turn the corner and you see it's a whole new street full of people who need our help.

Was the world capital of fossil fuels brought low by climate change? We asked Katherine Hayhoe, a leading atmospheric scientist at Texas Tech University.

Katherine Hayhoe: It's too early to tell. The postmortem will take years so to speak because climate science is all about the long term statistics we can say, absolutely without a doubt, that this hurricane took place over altered background conditions. Our planet is very different today than it would have been 50 or 100 years ago.

By "altered background" she means that the oceans of 2017 are on track to be the third warmest on record. Warmer water intensifies hurricanes three ways.

Katherine Hayhoe: First of all, in a warmer world more water evaporates into the atmosphere and so when a storm like a hurricane comes along there is so much more water vapor sitting up there for the hurricane to sweep up and dump on us. The second reason is sea level rise.

Scott Pelley: Water expands when it's heated.

Katherine Hayhoe: And that means when a hurricanes come along the storm surges on average will be stronger because there is more water behind them. And then the third way that we expect climate change to affect hurricanes is through warmer ocean waters. More energy, more power will be available to hurricanes in the future enabling them to intensify faster if conditions are right, as well as become more intense.

Scott Pelley: And that's apparently what we had with Harvey.

Katherine Hayhoe: We're starting to see it.

Scott Pelley: What have you lost?

Cynthia Neely: Three cars, most of our home, and our rental property, and half of our sanity.

Scott Pelley: You've been here 20 years, did it ever flood before?

Cynthia Neely: Never.

Scott Pelley: Is this house in a flood plain?

Cynthia Neely: No! No.

Hell hath no fury like a woman submerged. The crack of every ruined memory exposed Cynthia Neely's rage, not at Harvey, but at Houston. She's with "Residents Against Flooding," a 9-year-old group suing the city. They want to toughen the law that requires developers to dig detention basins to catch runoff from buildings. Houston has grown about 25 percent in 20 years.

Cynthia Neely: We hired top-notch hydrologists, engineers, to look at a problem and say, 'Hey, something is wrong here, city, county need to do something." And so for all these nine years we've been going to mayor after mayor, year after year, begging and pleading asking for detention basins asking for drainage infrastructure improvements and they just looked at us like, 'Thank you for coming, have a nice day.'

Scott Pelley: Why?

Cynthia Neely: Its costs money and because the city is bought and paid for by developers.

Scott Pelley: When you hear someone say these storms come along every 500 years or so you say what?

Cynthia Neely: Bulls***! OK, seriously? We have had three 500-year floods in the last 27 months. Now we have Harvey, Mother Nature is going to do what Mother Nature is going to do. That means its gonna rain, we're going to have hurricanes and tropical storms, so by golly do something to protect your people from it!

Scott Pelley: Mr. Mayor, I spoke to one of your constituents who uses words that I can't use on TV.

Sylvester Turner: OK.

Sylvester Turner has been mayor of Houston nearly two years.

Sylvester Turner: I understand why people are mad right now, because there are projects on the books and the only thing that stopped those projects from being built was the funding.

Scott Pelley: There is a sense among citizens who have flooded homes that there has been a lack of urgency about starting these major mitigation projects.

Sylvester Turner: I agree. I agree with them because you know all of these things are foreseeable.

Scott Pelley: So why have these things not been done Mr. Mayor?

Sylvester Turner: Because, because there hasn't been urgency on all levels to get them done. And that's the sad part.

The threat hasn't been ignored entirely. The federal government has spent more than $100 million in the county, over the years, buying up homes in the flood plain. But reams of flood control proposals fill the filing cabinets at City Hall.

Sylvester Turner: Sometimes it takes an event to occur that shakes people to their core. This storm has shaken people to their core. People don't want to hear the rhetoric and I understand that. The question, then, becomes are you, as elected officials and others, operating with the greatest degree of urgency?

These are those two flood control reservoirs that were built in the 1940s. They're usually dry, which is why you see trees. A 1996 study by the county flood control district called them "severely outdated." "it's…not hard to imagine," the study says, "that a single storm event could have a catastrophic impact…" a proposed fix was stopped by the cost, 600 million in today's dollars. But last month's 'catastrophic impact' will be tens of billions. The former head of the flood control district who promoted that study lives in this house.

He told us, from the 1940s to Harvey, planning for the reservoirs went from—quote-- "brilliance to neglect to stupidity to cruelty." Over the decades, thousands of homes were built on the flood plain.

Sam Brody: Hurricane Harvey was a human contrived disaster. If we have flooding, that is a natural process. A disaster is human induced because we've put so many people in these flood prone areas.

Sam Brody studies coastal development for Texas A&M university.

Sam Brody: I think that climate change is one driver of this problem. So the bay is rising we've measured that its going to continue to rise, but if you think of climate change as one of the drivers of flood loss it pales in comparison to human change and the development of the landscape, and putting people more in harms way, that is a much bigger driver of the problem.

Scott Pelley: Well people like development, people like to have jobs.

Sam Brody: And I think we need to promote that but doing it in a way that is smarter, which means protecting the ecological functions of our landscape, wetlands, pulling away from these bayous and over the long term we're going to have a more stable economy, better economic growth because we're not going to be dragged down by these chronic flood events.

Harvey is also rewriting emergency response plans. During the storm 160 helicopters and 17,000 troops rode to the rescue.

John Nichols: We didn't want to hold anything back we wanted to be more prepared than surprised.

Major General John Nichols commands the Texas Guard.

Scott Pelley: Did you have all the resources you needed to deal with this?

John Nichols: Yes sir, we did. We also had states that helped us 22 states brought helicopter. Four states brought troops.

Scott Pelley: If the storms of this size are going to be the norm in the future what are you going to have to do?

John Nichols: I don't know that its going to be the norm but that could be an option. We're used to a three day storm -- hurricanes come in they move fast and they go three days. We've not seen a storm that came in and lingered for six days. And drops 50 plus inches of water in one place.

General Nichols says, because Harvey exploded into a Category Four in just 48 hours, next time, he'll have to position his troops days earlier.

As the nation's fourth largest city begins to dry, ideas for the future include buying more people out of their homes in the flood plains, turning two, little used, golf courses into reservoirs, and building a massive seagate to shield the ship channel from the Gulf. Those projects would cost about $14 billion.

Back on Bramblewood Drive, we noticed the piano in Vince Shields' backyard. The green sticker guarantees the collapsed upright is, "Waterproof for 50 years," but in an age of warming oceans there are no guarantees. Folks on Bramblewood will have to decide whether to stay or go. Their past is no guide to the future.

Produced by Ashley Velie and Robert Anderson. Dina Zingaro and Aaron Weisz, associate producers.