How the gut's "microbiome" affects weight gain

Do you know what's in your "microbiome?" CBS News chief medical correspondent Dr. Jon LaPook is here to help you find out.

He spoke with microbiome researcher Dr. Ilseung Cho, assistant professor of medicine and associate program director of the division of gastroenterology at the NYU School of Medicine in New York City. Cho explained that every human being carries with them trillions of bacteria that live in the intestinal tract, on the skin, in saliva and elsewhere in the body.

Cho says there are about as many bacteria in an average human body as there are grains of sand on a mile-long stretch of beach. The mix of bacteria that flourishes in each of us makes up our microbiome.

But how does the microbiome affect our health and well-being? Studies are beginning to demonstrate that bacteria in the gut are involved in many bodily processes and areas of health and disease -- everything from weight control and ulcers to rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, and even heart disease. Cho's area of research in particular focuses on its role in obesity.

One example of the connection between the microbiome and weight gain is the role antibiotics appear to play in obesity, he pointed out. Farmers have been giving the drugs to chickens and livestock in an effort to fatten them up for decades, despite the Food and Drug Administration determining in 1977 that practice may be promoting antibiotic-resistance in people.

For a long time, Cho says, scientists couldn't explain the link between antibiotics and a heftier weight.

But research into the microbiome has shed light on how this occurs in animals, and in turn, suggested how antibiotic use in humans may be contributing to obesity by altering the bacteria that play a key role in regulating weight.

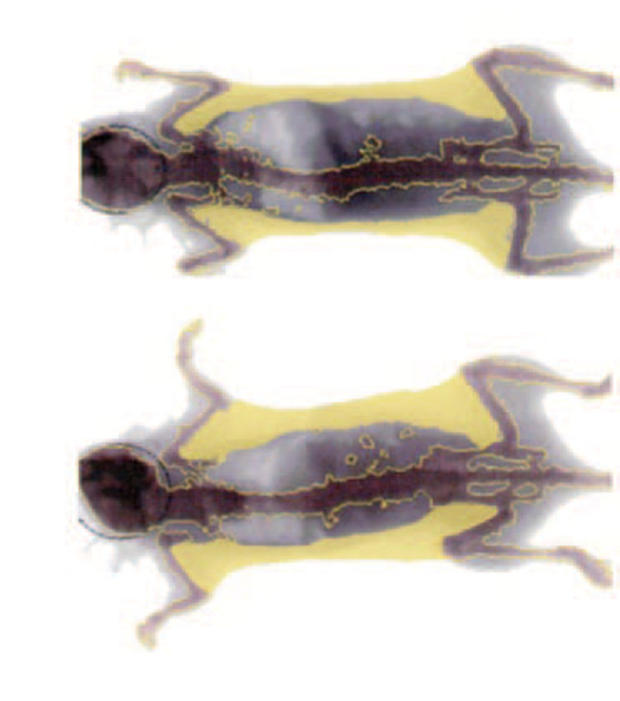

A groundbreaking study Cho and his colleagues published in Nature last year showed that young mice given low doses of antibiotics went on to develop significantly more body fat than mice that did not take antibiotics.

Some studies have found that children given antibiotics at an early age are more likely to have weight problems later, he added, and more research is underway.

In addition, other external factors may alter the bacteria found in the microbiome, including whether you were delivered naturally or by C-section. That's because a fetus is completely bacteria-free before birth, but during and after delivery, the child gets colonized with whatever bacteria it's exposed to. If it's a vaginal birth, that bacteria resembles what's found naturally in the mother's birth canal, but if the baby is born by C-section, exposure is limited to bacteria found on the skin, likely obtained when the child starts breast-feeding. There's some research that suggests children born vaginally are less likely to become obese, but that research is still ongoing, said Cho.

Given the research, could probiotics, or a transplant of "good" gut bacteria, be the cure for obesity?

Mice research suggests it might. Last month, scientists at Washington University in St. Louis transplanted intestinal germs from obese and lean people into mice who had been bred to be germ-free. The mice that received gut bacteria from the obese people gained more weight and experienced unhealthier metabolic changes than mice who received bacteria from the lean subjects, even though both sets ate the same amount of food.

Another study published last March by Harvard scientists took gut bacteria from mice that lost weight from a gastric bypass procedure, and other mice that underwent a placebo surgery, and transplanted them into germ-free mice. The mice who received bacteria from the gastric bypass group lost more weight, suggesting that bariatric surgery may alter the makeup of the microbiome.

Watch the video above with Dr. Cho and Dr. LaPook to find out more about microbiome research and how it could eventually help humans.

The Human Microbiome Project has more information on ongoing research.