How a death in Ferguson sparked a movement in America

One year ago, the nation watched as the city of Ferguson, Mo., erupted.

St. Louis police, dressed in riot gear, stood in a straight line, shields up and face masks down in a standoff with protestors. The media assembled on the sidelines, cameras poised to capture the latest. There was tear gas, burning buildings, chants and signs.

Protesters came armed with a message, a message that would echo through the Missouri night sky in the days and weeks after Michael Brown's death. It was a message heard across the nation in more protests for other black Americans who died by police hands. "Black lives matter," they chanted, wrote and tweeted. "Black lives matter," they chanted in throngs that blocked streets and demanded America's attention.

While demonstrators took to the streets of Ferguson and cities like New York and Los Angeles, a new generation of activists gathered both on the ground and online. The Black Lives Matter movement called for change with how police deal with minorities, and demanded a look at systemic racism and equity. And from it emerged a group of young people paving the way.

Brittany Packnett is one of them.

Packnett, 30, grew up in north St. Louis County in an African-American household lead by parents with advanced degrees. She is an activist, educator and a Member of the President's Task Force on 21st Century Policing.

She said the death of Michael Brown deepened her commitment to social justice.

"I think the most significant thing that has changed is that people can see this isn't just about Mike Brown, this isn't just about Tamir Rice, and it isn't just about Sandra Bland," she said. "It is about defending the humanity and the dignity of all people in this country and of people of color in particular."

The young movers and shakers who have been leading the Black Lives Matter movement are now one year out and reflecting back on how far the movement has come. And what else they think still needs to be done.

"I think what we have seen primarily change is that people recognize that here we are 365 days later and we are still talking about it," said Packnett.

Since Brown's Death

On Dec. 1, 2014, Packnett stood outside the Oval Office with seven other young activists. While she waited to meet with President Barack Obama she reflected on the fact that it was her enslaved ancestors who had built the White House.

"We were responsible in that moment to speak truths about our community to the leader of the free world, and that was a real opportunity, but it was also a real responsibility," Packnett recalled.

The president announced the formation of the task force that day, and in the weeks to follow Packnett would be named as a member. In May 2015, the President's Task Force on 21st Century Policing released a comprehensive report identifying best policing practices and offering recommendations to strengthen trust among law enforcement officers and the communities they serve.

A recent survey conducted by the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research revealed that one year after the death of Michael Brown, more than 3 out of 5 blacks say they or a family member have personal experience with being treated unfairly by the police -- and their race is the reason. The poll also revealed that nearly 3 out of 4 white people thought race had nothing to do with how police in their communities decide to use deadly force.

Activist and 25-year-old data scientist Samuel Sinyangwe, who lives in San Francisco, says the movement is making a difference anyway. He is a Stanford graduate who grew up in Orlando 15 minutes from where Trayvon Martin was killed. He helped found the website Mapping Police Violence after the death of Michael Brown.

"I had a lot of questions and I was frustrated by the fact that I couldn't get answers because the federal government was not collecting comprehensive information and data on police killings," he said. "What I wanted to know was how prevalent and how widespread are police killings. How are they potentially targeting black people and young black people in particular."

Sinyangwe collected data by using two large crowdsourcing databases on police killings. He says Mapping Police Violence has come to many conclusions, including "Ferguson is everywhere."

Sinyangwe's data has found that since 2015, at least 184 black people have been killed by police in the U.S. so far. In 2014, over 300 black people were killed. In the last year, Black Lives Matter has protested the deaths of black people including Freddie Gray, Walter Scott, Sandra Bland and Tamir Rice, to name a few.

"Not only is it happening everywhere, it's happening in some places more than others. We are able to shine a spotlight on why some of these uprisings are happening in some places," Sinyangwe said. "This is rooted in policy and the system can be changed."

Sinyangwe uses Newark, N.J. as an example. With about the same population and crime rate as St. Louis, and around the same amount of black people, crime in Newark is going down, Sinyangwe says. On the other hand, crime in St. Louis is going up. He says no black people have been killed by police in Newark since 2013, while 12 have been killed in St. Louis.

He says he hopes that the data Mapping Police Violence provides helps the problem of police violence be better understood, and helps towards addressing it.

Many of the protests held over the last year occurred after officers were not charged with crimes, as was the case in the deaths of Michael Brown, Eric Garner and Tamir Rice. But just last week, a prosecutor was quick to charge a Univ. of Cincinnati police officer with the death of Samuel DuBose during a traffic stop in Ohio.

An Associated Press analysis released in late July revealed that 24 states have passed at least 40 new measures after Ferguson. The AP reports that the measures have included addressing such things as officer-worn cameras, training about racial bias, independent investigations when police use force and new limits on the flow of surplus military equipment to local law enforcement agencies.

While the effects of these policies are new and not yet known, Sinyangwe says it is still progress.

"You really haven't seen anything as impactful as we are seeing this one right now in terms of seeing immediate legislation being proposed and passed and signed at all levels of government," he said.

Criticism

The Black Lives Matter movement hasn't come without its share of criticism. Some have called it anti-police, others anti-white; the majority of criticism has come from those on social media. The #BlackLivesMatter hashtag sparked another controversial hashtag as well, #AllLivesMatter.

"I thought it represented a real misunderstanding, that, unfortunately, happens often when marginalized people finally begin to tell our own story," said Packnett about #AllLivesMatter.

Saying black lives matter is not the same as saying only black lives matter, Packnett said.

"What it is saying though is an acknowledgement of the fact that black lives, brown lives, that people of color in particular, are the ones suffering disproportionately from issues of police brutality, police violence and discrimination in the criminal justice system," she said.

A CBS News/New York Times poll released in July revealed that nearly 6 in 10 Americans say they think race relations in America are bad. And among those polled, blacks are more likely than whites to hold this view. Nearly 8 in 10 African-Americans believe the criminal justice system is biased against them, up from 61 percent in 2013.

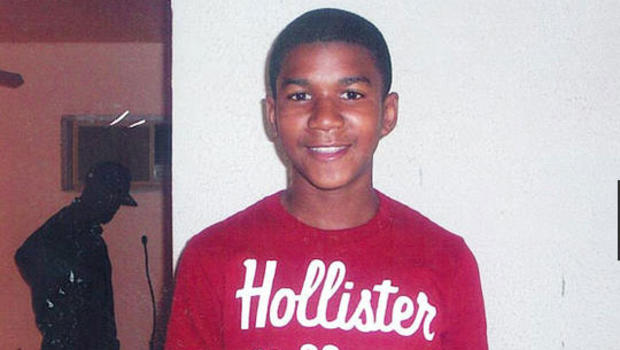

Black Lives Matter was sparked by a woman who tweeted it after the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the death of Trayvon Martin and it caught on, especially after the death of Michael Brown. It was also turned into an organization under the same name, Black Lives Matter. But the movement as a whole is also referred to as the Black Lives Matter movement.

As Packnett explained, the movement has faced criticism for not having a single leader, no one person the head of the movement.

A common misconception is that the movement is leaderless. But Packnett says it's actually "leader-full," and not being under the rule of one or two people allows many people to pursue change in the way they believe most beneficial and in a decentralized manner.

Sinyangwe said there is frustration from some people at the slowness of legislation, and he understands that. He said there is another common misconception about this movement, that nothing is happening. He says that's not true.

"Change is happening. And we will get free, but it is going to be a little while," he said. "What's happening really is unprecedented."

Social Media

Sinyangwe says Social Media has been the lifeblood of the movement.

"People would not have heard about Ferguson if it wasn't for social media. And when I say social media, I mean Twitter," he said.

Many of the activists have shared personal testimonies on Twitter, organized protests and spread their messages. It has also served as an educational tool for those outside of the movement.

"I think there is a misconception that the movement started with a hashtag," said Sinyangwe. "I think the movement started with everyday people."

But Sinyangwe says social media has still been powerful.

"It allows people to organize and build a community where it previously has not been," he said.

National conversation

Kayla Reed, 25, is field organizer for the Organization for Black Struggle. She is also a member of the Ferguson Action Council, a collaborative effort and coalition of organizations founded after the death of Michael Brown. She said the group comes together weekly to discuss action planning on the ground. The organization is responsible for the #UNITEDWEFIGHT weekend of events planned in Ferguson for the anniversary of Michael Brown's death.

Reed acknowledges that Black Lives Matter has now become a national conversation about race, and political candidates have had to answer questions about it. Most recently, Jeb Bush and Hillary Clinton have fielded questions about Black Lives Matter, as well as candidates during the first GOP debate.

"You are seeing both Republicans and Democrats having to address the issue of police accountability, injustice and the racial inequalities that exist in America in a way you haven't seen before," Reed said.

In late July, former Maryland Gov. Martin O'Malley was heckled on stage by demonstrators at the progressive Netroots Nation convention. The Democratic presidential candidate responded to the Black Lives Matter protesters by saying, "Black lives matter. White lives matter. All lives matter."

He has since walked back those comments, and, as Sinyangwe points out, he has recently released a comprehensive plan to address some of the issues the Black Lives Matter movement has raised.

What's next?

Sinyangwe would like to see the passing of a comprehensive package of federal legislation related to policing and criminal justice reform in the next year. In addition, he would like to see policies in police departments passed and enforced such as banning chokeholds, banning nickel rides, emphasizing deescalation, the carrying of non-lethal weapons and prohibiting shooting at moving cars -- to name a few.

Packnett said she too would like to see policies on paper become reality.

"What I am really looking to see is the foundation that we have laid to really turn into tangible outcomes and changes in peoples everyday lives," she said. "It didn't take just a year to get into this position. So it's going to take more than a year to get out of it."

She said she also hopes to see people continue to be creative, thoughtful and sustained in bringing forth what she calls a 21st Century human rights movement.

"I want to see us continue to live authentically as our generation does. I want to see some real wins that will help us figure out what the next win will be," Packnett said. "We will get there. We will keep going."