How plasma transfusions may heal COVID-19 patients

As Lona Towsley lay in the ICU at University Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin, battling COVID-19, the two-time cancer survivor felt like giving up. "I was trying to fight for my husband and my kids," she said. "But in my mind, it was getting way too hard. I didn't think I'd see my husband again. I was fighting to breathe. Stuff started coming up out of my lungs. I was just slowly strangling, was what it felt like."

Correspondent Allison Aubrey, of National Public Radio, asked, "You really thought this was the end?"

"I honestly did."

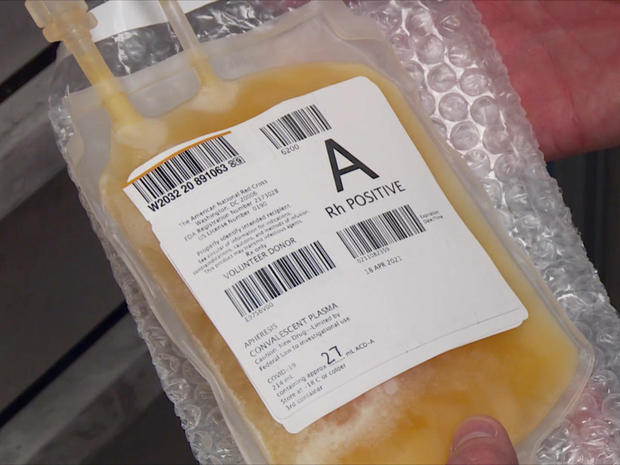

With Towsley's consent, her doctors administered an experimental treatment: a transfusion of plasma donated by someone who had just recently recovered from coronavirus.

"I believe that that's what saved my life," Towsley said.

Within a few days, Towsley went from being intubated on a ventilator to breathing on her own and feeling better.

"Were you surprised?" Aubrey asked.

"I was very surprised. I was thrilled. I had hope again," she replied.

More than 6,000 COVID patients have now received convalescent plasma. It's not clear yet how much it may help. But it's a technique that goes way back, and Dr. Arturo Casadevall, of Johns Hopkins University, stepped up to resurrect it

The procedure, he said, has been around for 120 years. "It was the subject of the first Nobel Prize," he said.

That's when doctors realized that virus-fighting antibodies borrowed from recovered patients may help prevent, or cure, disease. "I knew that there was an enormous body of experience with the use of convalescent plasma," Dr. Casadevall said. But much of this was lost to history. So, on February 27, he penned an Op-Ed in the Wall Street Journal, writing about a doctor at a boys' boarding school in Pennsylvania back in 1934, who treated a boy with a serious case of measles.

"So, what the doctor did was, he went to the kid who recovered, he took some of his blood, and they gave small amounts to the other children," said Casadevall. "And then they waited. And the epidemic that was supposed to have happened didn't happen."

His article was published just as the first coronavirus deaths in the U.S. were reported.

And at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York, Dr. Nicole Bouvier would soon be on the frontlines treating lots of patients.

"Yeah, I mean it's incredibly frustrating," she told Aubrey. "It's hard for the frontline doctors, the nurses. These are all people who are used to fixing things."

But at the time there was not a single approved treatment. So, behind the scenes, Dr. Casadevall scrambled to build a coalition of doctors. The first was Michael Joyner, of the Mayo Clinic; then, William Hartman of the University of Wisconsin; James Musser of Houston Methodist Hospital; Nicole Bouvier of Mt. Sinai; and Andreas Klein of Tufts Medical Center.

Dr. Joyner led the charge: "There was a crisis. So, people get into action mode when there's a crisis."

He worked with the FDA to expand access to plasma and get more hospitals on board. "We just got up every day and kept pushing. We just kept pushing, pushing, pushing," Dr. Joyner said.

Within weeks patients were being treated with convalescent plasma. Dr. Klein said what could have taken months or years happened quickly: "I think that's unprecedented. And is really inspiring."

Dr. Bouvier said, "It's unbelievable. I've never seen anything like this. I've never been part of anything like this."

Dr. Musser's team at Houston Methodist was among the first to treat COVID patients with plasma: "I view this as very much like an old-fashioned barnraising. You know, we'll aggregate and we'll get this done."

These doctors said convalescent plasma may be just a stop-gap measure until more treatments and a vaccine come along. Dr. Joyner said, "I think it'll be part of a cocktail. And hopefully then this paves the way for a vaccine. This was really the first kind of biological shot on a goal, and the first shot on goal, and the first best biological shot on goal."

And this feels good to Dr. Hartman, who treated patient Lona Towsley...

Aubrey asked, "What do you think you'll tell your children or grandchildren about this extraordinary moment?"

Dr. Hartman replied, "I'll tell them the story of a huge movement all across the country. That in six weeks' time, 2,000 hospitals have come together with the unifying purpose of trying to make people better. And in the end, it's the community that's saving the community."

Meanwhile, Towsley said she will donate her blood as soon as she's completely recovered: "If I can save just one person from going through what I went through, I'd do it in a minute."

Aubrey asked, "If you could meet the person who donated their plasma that was transfused into your body, what would you say to them?"

"Oh, thank you so much for giving me another chance at life!" Towsley said.

For more info:

- National COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma Project

- COVID-19 expanded access program

- Dr. Nicole Bouvier, Mt. Sinai Hospital, New York

- Dr. Arturo Casadevall, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore

- Dr. Michael Joyner, The Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

- Dr. William Hartman, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, Wis.

- Dr. James Musser, Houston Methodist Hospital

- Dr. Andreas Klein, Tufts Medical Center, Boston

Story produced by Kay Lim. Editor: Remington Korper.