How gerrymandering became one of the biggest issues in politics

As the 2020 Democratic primary takes shape, progressives across the country are once again taking aim at gerrymandering, the process by which state legislatures draw congressional maps to benefit one party over the other.

On Tuesday, for the second time in two years, the Supreme Court heard arguments about limiting the practice. The last time the high court considered gerrymandering, the justices declined to rule on the merits. And given the court's conservative lean, they could do so again in this most recent case, which involves House district maps drawn by state legislatures in Maryland and North Carolina.

The hope among those challenging gerrymandering is that these district maps were drawn in such a partisan manner that they violate the Constitution. And while liberals have taken the lead in challenging gerrymandering in recent years, the Maryland map was drawn up by Democrats, who also had partisan aims.

Former Democratic Gov. Martin O'Malley in a 2017 deposition, admitted his party's goal in its 2011 redistricting efforts was to make a GOP-held district in Maryland much more favorable to Democrats. In a 2018 USA Today op ed, O'Malley explained that 2010 had been a terrible year for Democrats, who helplessly watched "Republican governors carve Democratic voters into irrelevance in state after state in order to help elect lopsided Republican congressional delegations."

O'Malley said he saw it as his duty to "provide some check" against GOP governors by drawing a Democrat-friendly map. His effort was successful, and John Delaney won the seat from longtime GOP congressman Roscoe Bartlett in 2012. Delaney is now a Democratic candidate for president.

But by 2018, O'Malley regretted the move and said he hoped the high court would ban partisan redistricting.

The current governors of North Carolina and Maryland, Democrat Roy Cooper and Republican Larry Hogan, wrote an op-ed in The Washington Post earlier this week arguing that the Supreme Court should "end gerrymandering once and for all." Former Rep. Beto O'Rourke, a Democrat running for president, has made anti-gerrymandering efforts a central plank of his platform.

But ending gerrymandering might not be that easy, in part because both parties occasionally benefit from the process.

What is gerrymandering?

The word "gerrymandering" dates back to the early 19th century. The name comes from Elbridge Gerry, a Massachusetts governor who signed a redistricting bill that benefited his Democratic-Republican Party against the Federalists. One of the new districts was said to resemble a salamander, and so a Boston newspaperman decided to call the new map a gerrymander.

"The epithet at once became a Federalist war cry, the map caricature being published as a campaign document," wrote Charles Ledyard Norton in his 1890 book "Political Americanisms."

So gerrymandering is not a new phenomenon, having been a political issue for over 200 years. Since nearly the creation of the United States, House district maps have been littered with oddly-shaped seats that try to group together voters according to their partisan lean.

How gerrymandering works

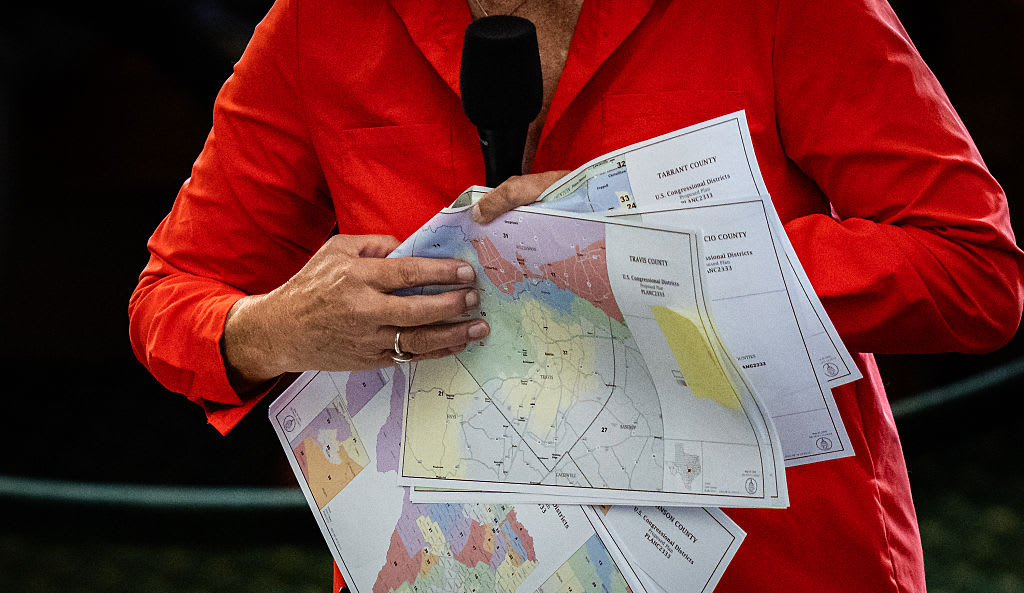

In most states, the legislature draws up new congressional maps following the conclusion of the U.S. census, which takes place every ten years. The state's governor then has to approve the new map by signing it into law.

This system was generally good news for Republicans following their landslide victories in the 2010 elections, which occurred the same year as the last census. The next round of redistricting is due to start in 2021, following the completion of the 2020 census.

It's impossible to know which party will enjoy the upper hand in drawing new maps following the 2020 elections, or whether the Supreme Court will step in to limit redistricting in the interim. A number of states, most recently Utah, have tried to sidestep partisan redistricting by creating independent commissions tasked with drawing maps that better reflect the will of voters.

How activists are looking to block partisan gerrymandering

Even if the Supreme Court chooses to once again sit out the fight over gerrymandering, state courts can sometimes step in. In 2018, for example, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court threw out a Republican-drawn map and instituted a new one that helped Democrats pick up several seats in the most recent midterms.

The rules governing redistricting are different from state to state, meaning that activists can't always depend on judges stepping in to redraw maps they see as unfair. At this point, four states use independent nonpartisan commissions to draw district lines.

States like Utah are also trying this approach, creating independent commissions that would limit legislatures' involvement in redistricting. The Utah law, which was narrowly passed by voters in the state last November, created a seven-person commission to draw up new maps and send them to the legislature for approval. California, the largest state with an independent redistricting commission, has a 14-member panel consisting of 5 Democrats, 5 Republicans, and 4 independents to draw new maps.

Former Attorney General Eric Holder now leads the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, a group that looks to back independent commissions and reduce GOP control of state legislatures. But given the Republican electoral success at the state level during the Obama years, Democrats still have their work cut out for them.

Democrats have scored major victories at the state level in recent elections, and according to The Washington Post, they would now have the ability to draw the boundaries of 76 House seats nationwide should redistricting happen tomorrow. But buoyed by its strength in southern states, the GOP would still be able to redraw 179 seats. Another 113 seats would be drawn by independent commissions, while 60 would be redrawn in states where Republicans and Democrats share control of the state government.

Why 2020 matters for gerrymandering

Unless the Supreme Court intervenes, the 2020 elections remain Democrats' best hope of undoing Republican gerrymanders and instituting new maps. And that means Democrats will have to expend major resources on capturing state legislatures and governorships while still looking to retake the Senate and the White House.

It's also something of an open question whether Democrats would restrain themselves from partisan gerrymandering in any states they take control of in 2020 and put in place independent commissions. It's easy to talk a big game about reform and fair maps in the minority. But as history has shown again and again, both parties tend to indulge in gerrymandering when given the chance.