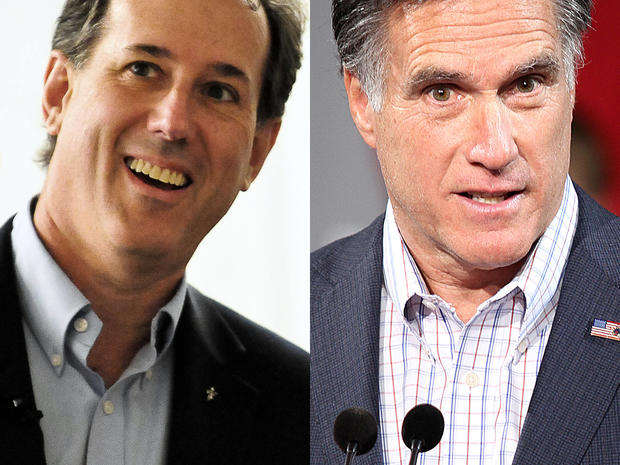

How does Romney slow Santorum's momentum?

Rick Santorum has all the momentum in the GOP presidential race: He leads Mitt Romney both in the latest CBS News/New York Times poll of Republican voters nationwideand in the crucial state of Michigan, which is one of the two states that come next on the primary calendar.

Romney has something working for him too, however: Time. There are ten days until the February 28 contests in Michigan and Arizona, a relative lifetime in this topsy-turvy Republican race. While Romney is a known quantity to most voters at this point, Santorum is something of a new face; until his three-state sweep last week, most Americans knew Santorum as a bit player in the presidential race - if they knew him at all.

The polls bear that out: According to the new CBS/NYT survey, one in two registered voters say they don't know enough about Santorum yet to form an opinion. That means the Romney campaign now has a prime opportunity to leverage its financial and organizational advantages to define the now relatively-unknown Santorum negatively in the minds of the American people.

Romney and his supporters have already begun a negative blitz against Santorum that mirrors the onslaught they offered up against former House Speaker Newt Gingrich after Gingrich won the South Carolina primary. Their focus in the short term is Michigan, where Romney was born and where many residents have fond memories of his father, who served as governor.

For Romney, a loss in Michigan would be humiliating. It would also give Santorum another momentum boost heading into the Super Tuesday contests on March 6.

His task is harder this time around than it was after the South Carolina primary. Gingrich was a relatively easy target: The Romney campaign was able to direct attention to Gingrich's "grandiose" pronouncements (including a call for a colony on the moon), the payments the former House speaker took from government-backed mortgage giant Freddie Mac, his messy personal history, and the ethics reprimand Gingrich received while running the House of Representatives.

Santorum doesn't have the same baggage - and he has successfully cultivated an air of working-class authenticity that both Romney and Gingrich lack. But that doesn't mean there isn't an opening for Romney. To understand what it is, consider what happened in Santorum's last campaign: The drubbing Santorum took at the hands of Democrat Bob Casey in the 2006 Pennsylvania Senate race.

Santorum, who had been in the Senate for a decade by the time, was caricatured in that race for his strong social conservatism, in part because of a 2003 interview in which he referenced "man on dog" sex in a conversation about homosexuality. Santorum had also written a book in 2005 called It Takes a Family in which he suggested that "radical feminists" undermined the family by convincing women "that professional accomplishments are the key to happiness."

Romney would no doubt love to point to that dynamic to argue that Santorum's strong social conservatism makes him unelectable in November. But he can't: Romney has already had to spend much of the campaign trying to convince skeptical conservatives he is one of them, and arguing that Santorum is too conservative plays right into his rivals' hands.

That inconvenient reality means that Romney has to go to what seems to be his next best argument: That Santorum, like Gingrich, is a backroom-dealing Washington insider who lacks fiscal discipline.

He has some ammunition. In the 2006 race, Casey pointed to Santorum's involvement in the K Street Project, an effort by Republicans to build a permanent majority in Congress by making sure that lobbying firms and trade groups hire Republicans for top jobs.

The idea, as reported in the Washington Monthly, was to create a Republican political machine "built upon patronage, contracts, and one-party rule" - with Santorum's weekly meetings with GOP lobbyists to discuss job placements and the legislative agenda playing a central role.

Casey suggested his rival had been exerting "undue influence" in a practice Casey described as close to "coercion," casting Santorum as a longtime politician more focused on Washington deal-making than helping his own constituents.

"I think the lobbyist thing really resonated because there was a sense that he went Washington," says Thomas Fitzgerald, who covers politics for the Philadelphia Inquirer. Santorum denies direct involvement with The K Street Project, though he doesn't deny the meetings took place.

Romney's opposition research team can also look to Santorum's post-Senate career, when he became a millionaire in part thanks to his Washington connections. While Santorum (like Gingrich) did not register as a lobbyist, he made money doing things that look an awful lot like lobbying - including the "relationship work" he did for the law firm Eckert Seamans, which retained him almost immediately after he left office. Santorum's tax returns, released on Wednesday, show that Santorum was paid hundreds of thousands of dollars as a consultant or board member to lobbying, energy and for-profit hospital corporations.

It's not easy to explain such relationships in a sound bite or attack ad, however. That's why Romney and his backers have so far focused on more low-hanging fruit: Santorum's practice of earmarking in Congress, his votes to raise the debt ceiling and his record on spending. (Check out an attack ad making these arguments from the pro-Romney super PAC "Restore our Future" at left.)

It's not clear that will be enough to really tie Santorum to Washington, however. Romney's success in Michigan may depend on his ability to push issues like The K Street Project into the public consciousness - which is why you shouldn't be surprised if you hear Romney raise the issue at the February 22 presidential debate in Arizona.

The risk for Romney is that even if he manages to take out Santorum in the primary, a Romney offensive could drive up Romney's own negatives in a way that both alienates GOP primary voters and hobbles him if he gets to the general election. It's enough to make you think that the 57 percent of Republican primary voters who say a drawn-out nomination battle hurts their nominee's chancesto win in November are on to something.