How did Google get so big?

This past month Sen. Orrin Hatch asked the Federal Trade Commission to investigate Google for possible violations of antitrust law and anti-competitive business practices, in part because of this story we aired last May. His request comes amid a flurry of high profile congressional hearings on the enormous, largely unchecked power accumulated by tech giants like Facebook, Amazon and Google over the last two decades. Of the three, Google, which is part of a holding company called Alphabet, is the most powerful, intriguing, and omnipresent in our lives. This is how it came to be.

Most people love Google. It's changed our world, insinuated itself in our lives, made itself indispensable. You probably don't even have to type Google.com into your computer, it's often the default setting, a competitive advantage Google paid billions of dollars for. No worry. Google is worth more than three-quarters of a trillion dollars right now and you don't get that big by accident.

Since going public in 2004, Google has acquired more than 200 companies, expanding its reach across the internet. It bought YouTube, the biggest video platform. It bought Android, the operating system that runs 80% of the world's smartphones and it bought DoubleClick, which distributes much of the world's digital advertising, all of this barely raising an eyebrow with regulators in Washington.

Steve Kroft: Were any of those acquisitions questioned by the antitrust division of the Justice Department?

Gary Reback: Some were investigated, but only superficially, the government just really isn't enforcing our antitrust laws. And that's what's happened. None of these acquisitions have been challenged.

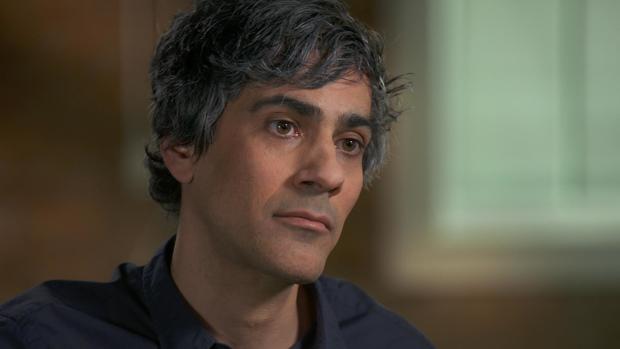

Gary Reback is one of the most prominent antitrust lawyers in the country widely credited with persuading the Justice Department to sue Microsoft back in the 90s, the last major antitrust case against big tech. Now he is battling Google.

Steve Kroft: You think Google's a monopoly?

Gary Reback: Oh, yes, of course Google's a monopoly. In fact they're a monopoly in several markets. They're a monopoly in search. They're a monopoly in search advertising.

Those technologies are less than 25 years old, and may seem small compared to the industrial monopolies like railroads and standard oil a century ago but Reback says there's nothing small about Google.

"People tell their search engine things they wouldn't even tell their wives... And that gives the company that controls it a mind-boggling degree of control over our entire society."

Gary Reback: Google makes the internet work. The internet would not be accessible to us without a search engine

Steve Kroft: And they control it.

Gary Reback: They control access to it. That's the important part. Google is the gatekeeper for-- for the World Wide Web, for the internet as we know it. It is every bit as important today as petroleum was when John D. Rockefeller was monopolizing that.

Last year, Google conducted 90% of the world's internet searches. When billions of people asked trillions of questions it was Google that provided the answers using computer algorithms known only to Google.

Jonathan Taplin: They have this phrase they use, "competition is just a click away." They have no competition. Bing, their competition, has 2% of the market. They have 90%.

Jonathan Taplin is a digital media expert and director emeritus of the Annenberg Innovation Lab at the University of Southern California. He says Google's expertise may be technology, but its business is advertising. And its most valuable commodity is highly specialized information about us. It's helped Google control roughly 60% of worldwide advertising revenue on the internet. Taplin says traditional companies can't compete because they don't have the data.

Jonathan Taplin: They know who you are, where you are, what you just bought, what you might wanna buy. And so if I'm an advertiser and I say, "I want 24-year-old women in Nashville, Tennessee who drive trucks and drink bourbon," I can do that on Google.

Gary Reback: People tell their search engines things they wouldn't even tell their wives. I mean, it's a very powerful and yet very intimate technology. And that gives the company that controls it a mind-boggling degree of control over our entire society.

Google is so dominant in search and search advertising that analysts and venture capitalists in Silicon Valley say it's extremely difficult for startups to get funding if their business model requires them to compete with Google for ad revenue.

Jeremy Stoppelman co-founded Yelp more than a decade ago -- a website that collects local reviews on everything from auto mechanics to restaurants nationwide and makes money selling ads.

Jeremy Stoppelman: The initial promise of Google was to organize the world's information. And ultimately that manifested itself in you expecting that the top links, the things that it shows at the top of that page are the best from around the web. The best that the world has to offer. And I could tell you that is not the case. That is not the case anymore.

Instead of doing what's best for consumers, Stoppelman says Google is doing what's best for Google.

Jeremy Stoppelman: If I were starting out today, I would have no shot of building Yelp. That opportunity has been closed off by Google and their approach.

Steve Kroft: In what way?

Jeremy Stoppelman: Because if you provide great content in one of these categories that is lucrative to Google, and seen as potentially threatening, they will snuff you out.

Steve Kroft: What do you mean snuff you out?

Jeremy Stoppelman: They will make you disappear. They will bury you.

Yelp and countless other sites depend on Google to bring them web traffic – eyeballs for their advertisers. But now Stoppelman says their biggest competitor in the most lucrative markets is Google. He says it's collecting and bundling its own information on things like shopping and travel and putting it at the very top of the search results, regardless of whether it belongs there on merit. He showed us how it worked by Googling sushi San Francisco.

Jeremy Stoppelman: All the prime real estate is here. This is where the consumer, their eye focuses. And that's by design; Google wants you to pay attention to their content.

All of the information here is owned by Google from the maps to the reviews. Stoppelman says if you click on any of these links at the top of the page you may think you've gone to another website but in fact you will still be on Google, seeing what it wants you to see while it collects your personal information and maybe exposes you to Google advertising.

Steve Kroft: If you click anything inside this box, you stay on Google and they make more money?

Jeremy Stoppelman: That's right.

"Google wields enormous power across the industry. And they set the rules. The question is who's watching Google?"

Google told us it doesn't have anything to do with money, it's about improving its product by making searches quicker and easier for its customers by eliminating the need to click through lots of other sites.

Stoppelman says it's about stifling competition, pushing it down the page where it's less likely to be seen. The advantage, he says, is even more striking if you look at the search results on a smartphone.

Jeremy Stoppelman: This is exactly what your phone would look like in the palm of your hand. This is all of Google's own property, right here. It takes up the entire screen.

Steve Kroft: How important is that first page?

Jeremy Stoppelman: It's not even just the first page, it's the first few links on the page is the vast majority of where user attention goes, and where the traffic flows.

Steve Kroft: So if you're not at the top of the page or at the bottom of the first page, or on the second page, that's gonna affect your business?

Jeremy Stoppelman: Yeah, if you're on the second page, forget it you're not a real business.

Yelp, Microsoft, Amazon, eBay, Expedia, and Yahoo all complained about Google's dominance and what they called its anti-competitive behavior to the Federal Trade Commission, which in 2011 conducted an investigation.

According to a confidential memo – parts of which were inadvertently given to the Wall Street Journal years later – the FTC's Bureau of Competition had recommended that an antitrust lawsuit be filed against Google for some of its business practices. It said "Google is in the unique position of being able to 'make or break any web-based business'" and "has strengthened its monopolies over search and search advertising through anti-competitive means" and "forestalled competitors and would-be competitors' ability to challenge those monopolies." It specifically cited Google for stealing competitors' content, and imposing restrictions on advertisers and other websites that limited their ability to utilize other search engines. But the recommendations were rejected.

Gary Reback: It flatly says that Google's conduct was anti-competitive. It flatly says that Google's conduct hurt consumers. I mean, what else would you need to know to vote out a complaint? There it is, written by your own staff. And yet, nothing happened.

Steve Kroft: They closed the case?

Gary Reback: They closed the case, correct.

The FTC's commissioners decided that Google's conduct could be addressed with voluntary improvements to some of its business practices - and that Google's decision to move its own products to the top of the search page could plausibly be of benefit to consumers. But Reback and others who were directly involved in the investigation have long suspected that the outcome had something to do with Google's political muscle in Washington and its close relationship with the Obama administration. Google spent more money on lobbying last year than any other corporation, employing 25 different firms and helping fund 300 trade associations, think tanks and other groups many of which influence policy.

Gary Reback: They have a seat at the table in every discussion that implicates this issue at all. They know about developments that we never even hear about. So their influence – from my perspective is very, very difficult to challenge.

Until now the only one taking aggressive action against Google and big tech is Margrethe Vestager, the competition commissioner for the European Union. Vestager has become a thorn in the side of Silicon Valley, fining Facebook $122 million for a merger violation and ordering Ireland to recover $15 billion in taxes owed by Apple. Last year, she levied a $2.7 billion fine against Google for depriving certain competitors of a chance to compete with them.

Margrethe Vestager: Just as well as I admire some of the innovation by Google over the last decade-- well, I want their illegal behavior to stop.

Steve Kroft: And that's what you feel has gone on.

Margrethe Vestager: Not only do we feel it, we mean that we can prove it.

In researching the case, Vestager says her staff went through 1.7 billion Google search queries and found that Google was manipulating its secret search formulas—or algorithms—to promote its own products and services and sending its competitors into oblivion.

Margrethe Vestager: It's very difficult to find the rivals. Because on average, you'd find them only on page four in your search results.

Steve Kroft: And why so far down?

Margrethe Vestager: Well, because then you don't find them. I don't-- I don't know anyone who goes to page four in their search result. The-- jokingly, you could say that this is where you should keep your secrets. Because no one ever comes there.

Steve Kroft: Do you think this has been deliberate on Google's part?

Margrethe Vestager: Yes. We think that this is done on purpose.

Steve Kroft: How do they do it? I think everybody has this idea that Google has this algorithm. And they put the best searches right at the top.

Margrethe Vestager: Well, it is exactly the algorithm that does it. Both the-- the promotion of Google themselves and the demotion of others.

Steve Kroft: So, they're rigging the game.

Margrethe Vestager: Yes. And it is illegal.

Google has paid its 2.7 billion fine and is aggressively appealing the decision. But for now, Stoppelman says everyone is still playing by Google's rules.

Steve Kroft: If you're in business, you have to be on Google.

Jeremy Stoppelman: Yeah. Google wields enormous power across the industry. And they set the rules. The question is who's watching Google?

Since the story aired in May, the European Union has levied another record fine against Google, this one $5 billion, for anti-competitive practices involving its Android mobile software.

Google declined our request for an interview with one of its top executives. It has also declined to make them available to testify at hearings before Congress. In a written response to our questions the company denied it was a monopoly in search or search advertising, citing many competitors including Amazon and Facebook. It says it does not make changes to its algorithm to disadvantage competitors and that, "our responsibility is to deliver the best results possible to our users, not specific placements for sites within our results. We understand that those sites whose ranking falls will be unhappy and may complain publicly."

Produced by Maria Gavrilovic. Associate producer, Alex Ortiz.