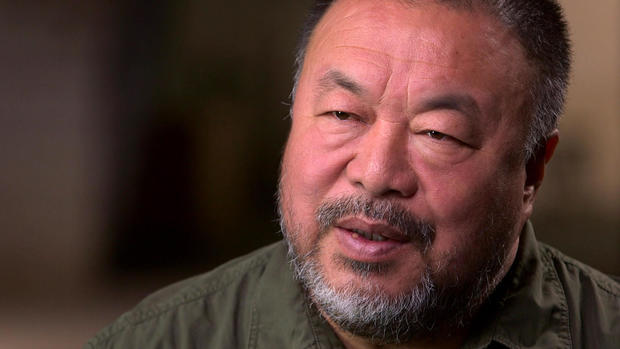

How Chinese artist Ai Weiwei became an enemy of the state

Ai Weiwei is China's most famous political dissident; a provocateur and a troublemaker whose clashes with the Chinese government have gotten him harassed by police, thrown in jail and driven out of the country. He's also one of the most successful contemporary artists in the world; a designer, sculptor, photographer and blogger who, as we first told your earlier this year, has earned legions of followers by using his art as a weapon to ridicule the authorities. And we should warn you: some of his work can be offensive. But when you meet Ai Weiwei, he's soft-spoken, self-deprecating and shy; the last person you'd expect to be an enemy of the state.

Holly Williams: They thought your intention was to subvert state power.

Ai Weiwei: Which is true.

Holly Williams: Which is true. You want to bring down the Chinese government?

Ai Weiwei: Not bring down. I don't think I have the power to bring it down.

Holly Williams: But you want it to change?

Ai Weiwei: Yes. Of course.

Those are dangerous words in China where even after decades of modernization the government has little tolerance for dissent. But that's never bothered Ai Weiwei.

This is the work he's perhaps most famous for…what you're seeing in the background is a portrait of China's revered former dictator Mao Zedong...part of a series in which Weiwei gives the finger to other symbols of power around the world.

Ai Weiwei: --just like this.

Holly Williams: It-- --are-- are we creating a new Ai Weiwei as we stand here?

Ai Weiwei: You can see. It's so easy. Everybody can do it.

Easy, certainly not subtle, and maybe a little silly. But the Chinese authorities took them very seriously...they thought it was subversive.

Holly Williams: Why was the regime frightened of art?

Ai Weiwei: Because they're afraid of freedom, and art is about freedom.

Holly Williams: They're afraid of freedom.

Ai Weiwei: Yes.

Holly Williams: Are you an artist, or are you an activist?

Ai Weiwei: I think artist and activist is the same thing. As artist, you always have to be an activist.

Holly Williams: You have to be political to be a good artist.

Ai Weiwei: I think every art, if it's relevant, is political.

Evan Osnos: That's the purpose of his life. I mean, as a dissident, as an artist…

Evan Osnos is a writer for The New Yorker who spent years in Beijing and chronicled Ai Weiwei's confrontations with the authorities. He calls him an "entrepreneur of provocation."

Holly Williams: What does that mean?

Evan Osnos: It means that no matter what he's doing, he's figuring out a way not to cooperate with the prevailing wisdom or the people in charge. And this can make a lot of people very angry.

Holly Williams: What's wrong with how things are to Ai Weiwei's mind?

Evan Osnos: In China, you are being constantly told that the world today is so much better today than it was 20 or 30 or 40 years ago when Chinese people were literally starving. That you should be satisfied. And what Ai Weiwei is saying is, "Absolutely not. You should demand more."

Holly Williams: It's not good enough to be rich?

Evan Osnos: Exactly. It's not good enough to be rich; you need to be free as well.

In 2008, Ai Weiwei's one-man rebellion turned into a war with the Chinese government after a massive earthquake shook Sichuan Province. It killed almost 90,000 people, including several thousand children, many of whom were crushed in poorly-built government schools. It was a national trauma, and the authorities tried to put a lid on the public's anger by covering up the number of children who died.

Holly Williams: It was a state secret how many children had died in these schools?

Ai Weiwei: Yeah. They always use that-- as-- some kind of, you know, excuse not to give you the correct numbers.

Weiwei assembled a team of activists to interview the parents, many of whom had lost their only child. He called it a "citizens' investigation"... China had never seen anything like it.

Holly Williams: So you were trying to get to the truth. Why did that make the Chinese government so angry?

Ai Weiwei: To control the information, to the limit the truth. It's most efficient tactics for totalitarian society-- for the rulers.

He gathered the names of more than 5,000 dead children and published a list on the Internet, shaming his government. And across China people took notice.

Holly Williams: It was a challenge to the government's authority?

Evan Osnos: And they couldn't accept it. It was an act of radical transparency. Nobody had ever done that before. And they didn't immediately know how to respond. They had never really encountered a person like Ai Weiwei.

Holly Williams: What were they worried that he might do?

Evan Osnos: Inspire people. Inspire people to do and live the way that he did.

The Chinese authorities responded brutally. Ai Weiwei says police beat him up and he later had to be hospitalized. Doctors discovered bleeding in his brain which he says could have killed him.

He documented it all on social media for his followers around the world, infuriating the government and escalating the confrontation.

Evan Osnos: He weaponized social media. He figured out that in a country in-- that controls information so carefully, that seizing the tools of information distribution is a very powerful thing to do.

Holly Williams: What did the Chinese government think about that?

Evan Osnos: They began to think he was a very dangerous person.

Ai Weiwei was groomed to be a dissident since childhood. His father, Ai Qing, was a celebrated poet who was denounced as a traitor and exiled with his family to the edge of China's Gobi Desert where Weiwei watched his father's humiliation as he was forced to clean public toilets.

Holly Williams: You were an outsider from the beginning.

Ai Weiwei: Yes, I'm a natural outsider. I always been pushed out, and-- but that also give me very special angle to look at things.

Holly Williams: It made you an independent thinker.

Ai Weiwei: It made me a individual and I was always having to make my judgement independently because the mainstream will never accept somebody like me.

Weiwei got out of China at the first opportunity, moving to New York in the early 1980s. He was intoxicated by the city, chronicling everything in pictures, drawing inspiration from American masters like Andy Warhol and stringing together a living doing odd jobs and street art.

Holly Williams: So you were drawing portraits of people and--

Ai Weiwei: Yeah.

Holly Williams: --selling them for how much?

Ai Weiwei: Fifteen-- $15.

Holly Williams: $15?

Some of his work now sells for millions, but in America he discovered something you can't put a price on.

Holly Williams: You once said that once you've experienced freedom, it stays in your heart.

Ai Weiwei: Uh-huh (affirm).

Holly Williams: Is that true?

Ai Weiwei: Yeah, it's true. I think it's true. You taste the most important thing in life. And you will never forget it. Yeah.

After a decade in the U.S., he moved back to China and set up a studio in Beijing; breaking new ground and challenging old sensibilities with mischievous, provocative art.

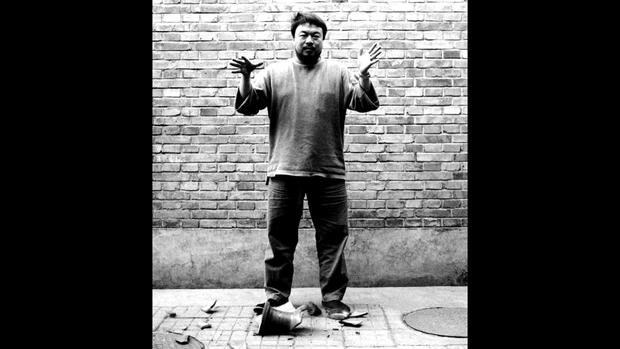

Like this piece in which Weiwei photographed himself destroying a 2,000-year-old Chinese urn. He wants to shatter the Communist Party's official version of history.

Holly Williams:You smashed a priceless urn.

Ai Weiwei: It's not priceless.

Holly Williams: For a lot of Chinese people it's-- it's a priceless part of their history.

Ai Weiwei: For me, to smash it is a valuable act.

If you buy that…and the art world certainly did…look at what he did to these urns doused in bright paint or emblazoned with the Coca-Cola logo, paying tribute to his idol, Andy Warhol.

By 2010, new commissions were rolling in and Weiwei's work grew more ambitious. Not all of it was political. He cast giant-animal heads in bronze and sent them on tour around the world. He hired 1,600 artisans to handcraft porcelain sunflower seeds then carpeted the floor of a giant atrium in London with 100 million of them. It captivated the public and helped turn Ai Weiwei into an art-scene superstar.

Holly Williams: You're the darling of the art world.

Ai Weiwei: I'm a darling of art world. I don't really care.

Holly Williams: You don't care.

Ai Weiwei: No, I don't really care. They can just forget about me. I don't care.

Holly Williams: But they're not forgetting about you.

Ai Weiwei: Well, that's their problem, you know? They should. They should learn how to forget about me.

The Chinese government wanted everyone to forget about Ai Weiwei, blocking his name on the Internet in China and making it impossible to search for him. But that didn't stop Weiwei from needling the authorities relentlessly. When they put his studio under surveillance, Weiwei decorated the cameras with lanterns, then fashioned replicas out of marble for his exhibitions.

When officers were ordered to follow his every move, he got his own camera man to film them filming him, ridiculing the state in a way no one else in China had ever dared.

Evan Osnos: I mean, in a way, people have learned to be, "Keep your head down."

Evan Osnos: And Ai Weiwei doesn't. He's, "No. I'm not gonna keep my head down. I'm gonna wave my big head with my beard and my crazy haircut all over the place and you'll have to deal with it."

Holly Williams: He was making the Chinese government look ridiculous.

Evan Osnos: Yeah. He was mocking it. He was mocking it. And the Chinese government is many things, but it is not possessed of an abundant sense of humor. And I think, you know, at a certain point, they said, "We're not gonna take it anymore."

And they didn't. Early one morning in 2011, as he was about to board a plane, they put a hood over his head and took him away. It was the beginning of 81 harrowing days in solitary confinement under 24-hour surveillance.

Holly Williams: They watched you shower. They watched you use the toilet. They watched you when you were asleep at night. They were trying to humiliate you.

Ai Weiwei: I think that's the very routine way when they detain somebody they think is very important.

Holly Williams: Were they trying to break your spirit?

Ai Weiwei: I think-- they don't have to try.

Holly Williams: Did they break you?

Ai Weiwei: Somehow, I think.

When he was released from detention, his passport was confiscated and he was forbidden from speaking publicly.

Ai Weiwei: I cannot talk, I'm so sorry.

But Ai Weiwei couldn't help himself. He recreated his prison cell with these three-dimensional models, which were exhibited around the world.

It helped pile pressure on the Chinese government and two years ago, he was finally given his passport back.

Within days he was on a plane out of China…setting up a new studio in Berlin. When we visited him, he'd shifted his attention to the plight of refugees struggling to reach Europe; turning these clothes they discarded into a new work.

He told us he's staying in Europe for the time being out of concern for the safety of his young son. But he hasn't ruled out moving back.

Holly Williams: Ai Weiwei has now left China. Doesn't that mean that the Chinese government has won?

Evan Osnos: I don't think so. I think-- I'm not sure how far we are into the game here. But the game is not over.

Holly Williams: He might start the fight again with the Chinese regime?

Evan Osnos: I would not be surprised. I mean, it-- any time people have sort of counted him out-- they've been proven wrong.

Produced by Michael H. Gavshon and David M. Levine.