Horse racing cleaning up its act with watchdog monitoring racetrack safety, anti-doping rules

The Justice Department is winding down one of the biggest horse doping investigations in U.S. history. Tonight, you'll hear the incriminating wiretaps that helped crack the case; convicting 29 veterinarians, horse trainers and drug distributors.

Horse racing, known as the sport of kings, found its crown badly tarnished last spring when a dozen horses died during the weeks surrounding the Kentucky Derby. And just days ago in California, two horses died before the Breeders' Cup.

Horse racing has reached its moment of reckoning, and we wanted to know: can the sport really be reformed — or is it too late?

It was a sweet finish to this year's Kentucky Derby.

A stealth newcomer named Mage defying 15 to one odds to win the race.

But the celebration at Churchill Downs capped off a startling run up to the race. Five horses were scratched including the favorite, Forte. And then there was the death toll: a dozen at the height of this year's season, leading the track to temporarily suspend racing. Investigators were unable to find a singular explanation for their fatalities.

Take Charge Briana injured her front leg and was euthanized.

Lost in Limbo hurt his leg, collapsed on the track and was later put down.

Then in Maryland, on the day of the Preakness Stakes, this horse named Havnameltdown threw off his jockey after injuring his front leg and also had to be euthanized.

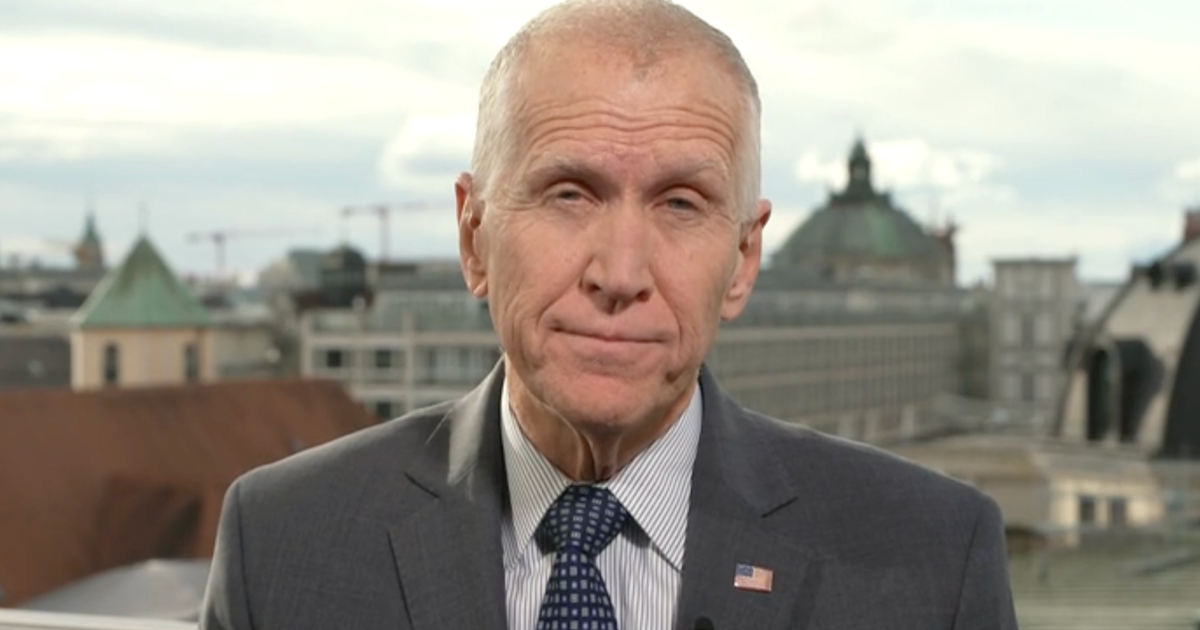

In June, we spoke with the woman newly charged with trying to make the sport safer: Lisa Lazarus, the chief executive officer of HISA — the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Authority.

Cecilia Vega: People who are not in your world see this headline of more than a dozen dead horses and they think, "What is going on in that industry?"

Lisa Lazarus: And my response to that is HISA is here now and we're gonna address it.

Lazarus was legal counsel for the international governing body of Equestrian Sports and spent her childhood going to the racetrack with her father. She joined HISA last year after it was created by Congress – the most sweeping effort yet to clean up the sport which for years has grappled with drugs and cheating.

Lisa Lazarus: There's clearly a problem that needs to be addressed. And now we've got some tools to fight it. And so we really owe it to those trainers who have spent their lives in this-- in this sport and who are, you know, who have an incredible amount of integrity to get rid of those that are really tarnishing the sport.

Cecilia Vega: We're talking about the most high-profile races of the year in this country. Do you think drugs had anything to do with these deaths?

Lisa Lazarus: You know, it's a great question. Now that we have oversight over-- over all of it, I feel a lot more confident that we're gonna be able to do our job.

Just days after we met Lazarus at Belmont Park in New York, two more horses died at that very track after injuring their legs.

The deaths have added to questions about the future of the sport — and whether HISA can improve safety and stay ahead of corrupt trainers and veterinarians who have taken extraordinary steps to outsmart regulators.

Cecilia Vega: How big of a problem is doping in horse racing?

Stuart Janney: It's a big problem it strikes at the integrity of this-- of the sport. It's not good for the horses. Uh, there's just nothing about it that is acceptable.

Stuart Janney is a man whose pedigree is legendary in the horse racing world. His family once owned the champion thoroughbred Seabiscuit.

As chairman of The Jockey Club — an organization that registers thoroughbreds — Janney testified before Congress in 2018 and called for establishing a national anti-doping program.

Stuart Janney (during his testimony): This issue is extremely important to the thoroughbred industry and especially to The Jockey Club, which has been advocating for medication reform in our sport for decades.

Cecilia Vega: In a word, could you describe what horse racing regulation has been like in the last 50 years?

Stuart Janney: A failure. And increasingly so.

Cecilia Vega: It's gotten worse?

Stuart Janney: It's gotten worse. And quite frankly states have not done their job.

For decades, the sport was entirely overseen by state racing commissions that struggled to stop repeat drug violations, notably by the sport's most high-profile trainer Bob Baffert. Baffert has been cited for dozens of drug violations in connection with some of his horses over the last four decades. He was suspended by Churchill Downs in 2021 after his horse Medina Spirit won the Kentucky Derby but was later disqualified after testing positive for a banned substance.

Cecilia Vega: I gotta tell you, when you talk about something that sounds like it is as institutionalized as corruption has been. I don't know how you clean that up.

Stuart Janney: Well, I think you put people away. You-- you send them out of the sport. And some of 'em go to jail.

In March of 2020, a set of sweeping federal indictments laid out the extent of the corruption — with doping and animal cruelty on full display at the highest levels of the sport.

According to the indictments, veterinarians and trainers plotted to give horses banned substances they called "monkey" and "red acid" to make them run faster — including the same kind of blood builders cyclist Lance Armstrong took.

Prosecutors said they also used pain killers, including snake venom, that deadened nerves so the horses could run through injuries.

The FBI said it led to broken legs, cardiac issues, and in some cases death.

Using a trove of wiretaps, the Justice Department charged 33 veterinarians, trainers and drug distributors — including some of the biggest names in the business, like Jason Servis who trained Maximum Security, the first place finisher at the 2019 Kentucky Derby before the horse was disqualified for interference by drifting outside his lane. Prosecutors also charged top earning trainer Jorge Navarro, heard on this expletive filled wiretap bragging to another trainer about how the drugs made his horse run faster.

Jorge Navarro (on a recording): I f****** gave it to this horse – this motherf***** galloped – galloped!

Trainer (on a recording): OK.

Jorge Navarro (on a recording): Yes.

Trainer (on a recording): Amino acid.

Jorge Navarro (on a recording): Yeah, some amino acid injectable. Small bottle.

Navarro's reputation for doping horses was such an open secret prosecutors say he went by the nickname "the Juice Man" and wore it on his shoes like a badge of honor. That's him on the right in the dark pink shirt…

Navarro administered banned drugs to one of his most famous horses X Y Jet ahead of a race in Dubai where the horse won a million and a half dollar prize.

According to the indictment, Navarro said, "I gave it to him through 50 injections… I gave it to him through the mouth." The following year, Navarro announced that X Y Jet died from a heart attack. It stood out to Shaun Richards, the lead FBI agent on the case.

Cecilia Vega: In those wiretaps/ you hear Navarro telling another trainer how close he came to getting busted. He says he would've been caught, quote, "pumping and pumping and fuming" every horse that ran that day. You hear that and you think what?

Shaun Richards: We're right where we need to be./ you know we have a really, really good subject identified, and we're gettin' fantastic evidence.

He spent his childhood on a horse farm and his career busting Russian mobsters. Both proved invaluable in infiltrating the dark side of the horse racing world.

It didn't take long for Agent Richards to figure out that vets and drug distributors were constantly finding ways to outsmart the testing system.

Shaun Richards: They would change one molecule in that sequence. And now, even if they had a test, if they don't have the latest test for that substance, they'll never find it.

Cecilia Vega: So an investigator comes in with a test looking for this drug. They tweak it by a molecule here or there.

Shaun Richards: Now your test is no good. If it's not testable, they can't get in trouble for it.

Cecilia Vega: This game of cat and mouse that they're playing to stay ahead of investigators is how dangerous to the horses being injected?

Shaun Richards: It's terrible. Y-- you don't know what's in those substances.

Much of the evidence in the investigation began with one man's gut feeling. New York commercial real estate magnate Jeff Gural is an owner of Meadowlands racetrack in New Jersey — the biggest venue in the country for harness racing, a niche betting sport where horses pull drivers in carts.

Cecilia Vega: What had you seen that made you suspicious that drugs were that rampant?

Jeff Gural: You would see horses that were going a certain speed, and then the new trainer would take over, and the next week the horse would be two seconds faster.

Cecilia Vega: And in that, in your opinion, is a giant red flag?

Jeff Gural: It's impossible.

Cecilia Vega: It's impossible?

Jeff Gural: It-- it's impossible to get a horse-- to go two seconds faster. And you would see it consistently.

Cecilia Vega: What do you think drove these guys?

Jeff Gural: Greed. The same thing that drives everybody.

So Gural outright banned trainers he suspected of doping — and hired retired state police officer Brice Cote to conduct surprise blood and urine tests.

Jeff Gural: If you wanted to race here, you had to sign an agreement that said that we can show up at any time and ask your veterinarian to supply us with a drug sample. And we can do whatever we want with it.

Cecilia Vega: Unannounced testing.

Jeff Gural: Unannounced, that's the key. Just like baseball and football.

Cecilia Vega: And what were the results?

Jeff Gural: Most of the samples came back negative, but some came back for drugs that nobody knew about.

Gural then hired the investigative firm 5 Stones.

Stuart Janney and The Jockey Club had also hired 5 Stones, which had worked for the world anti-doping agency's independent commission investigating Russian doping in track and field.

Cecilia Vega: did you give them any specific instructions in terms of who they should or should not go after?

Stuart Janney: Yes. I said, "I'm not interested in you going and finding a relatively unimportant person working in somebody's barn that has made a bet they shouldn't have made or done something that's, you know, immaterial to what we're talking about."

Cecilia Vega: You wanted big fish.

Stuart Janney: "I want you to go after the important people that I think are corrupting the sport."

Janney got what he wanted.

5 Stones passed its leads to the FBI's shaun richards, who gathered a mountain of evidence, including this wiretap where, according to investigators, trainers Jason Servis and Jorge Navarro are heard stressing just how bad it would be if they got caught with illicit drugs.

Jason Servis (on a recording): We can't do it in broad daylight, we gotta do it like –

Jorge Navarro (on a recording): I know, I'll keep it at my, I'll keep, I'll keep it in my car, I ain't worried about that.

Jason Servis (on a recording): What about, what a, I am — I don't want — people see that s*** we are dead — we're dead.

And investigators say this wiretap captured trainer Nick Surick talking about covering up for Navarro.

Nick Surick (on a recording): You know how many f****** horses he f****** killed and broke down that I made 'em disappear?

The FBI found hundreds of vials linked to veterinarian Seth Fishman, heard in another wiretap boasting about his drugs.

Male voice (on a recording): I'm mostly looking to ah — for performance enhancing.

Seth Fishman (on a recording): Well, there's all levels, I mean, that's where we can speak in person, you can go with something for pain or you can do something to increase blood, I mean, that's you know, there's many options, you know.

Cecilia Vega: You're a horse guy.

Shaun Richards: Mmhm.

Cecilia Vega: Where does that sit with you?

Shaun Richards: It's completely wrong. to pump these horses full of stuff that you don't know what's in 'em, for-- you know, a potential chance to win at a higher rate, it's disgusting behavior.

Seth Fishman was sentenced to 11 years in prison. The Juice Man, Jorge Navarro, and Nick Surick were sentenced to five years and, this past July, Jason Servis to four – all for doping-related crimes.

Cecilia Vega: How long is it going to take to clean this up?

Lisa Lazarus: It'll probably take years to be-- to be truly confident that we've got a fully clean sport.

Since HISA's anti-doping program opened its doors in May, 33 trainers in the United States have been suspended for banned substances. This past summer, at the Saratoga Race Course in New York, 13 more horses died. Those deaths are under investigation.

Produced by Sarah Koch. Associate producer, Madeleine Carlisle. Broadcast associate, Katie Jahns Edited by Matthew Lev.