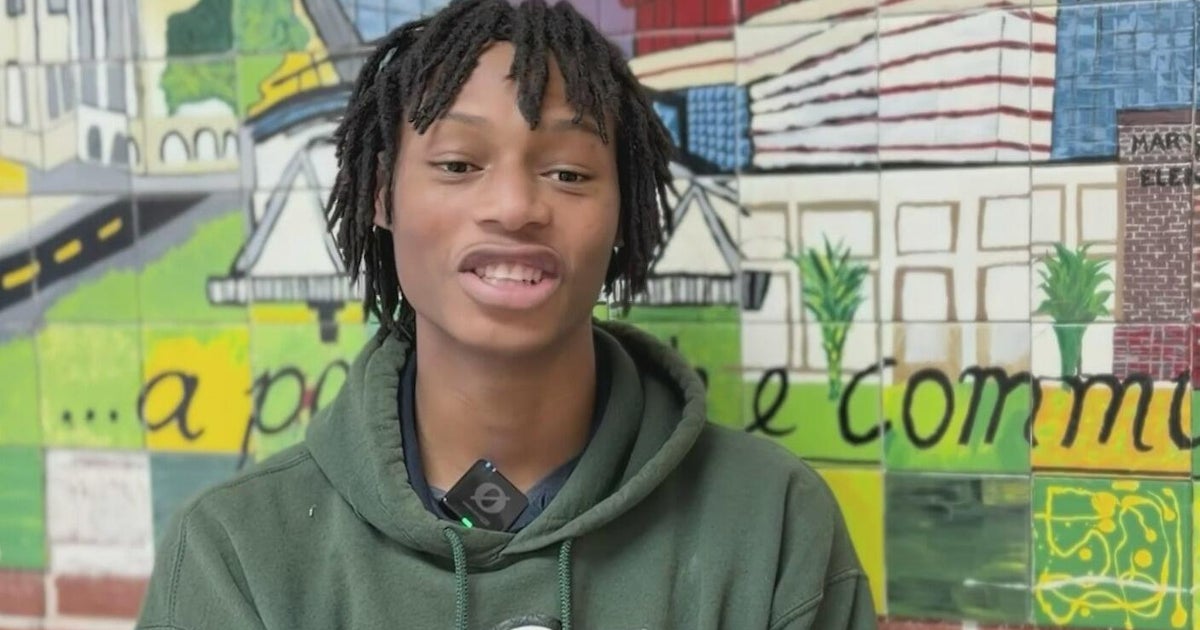

Makur Maker spurned top college hoops programs to play at a historically Black school

When Makur Maker, one of the nation's top young basketball prospects, was considering where to attend college, he visited schools like UCLA and the University of Kentucky known for their hoops history. But a visit to Howard University put him on a different path, though one also steeped in history.

The 6'11" incoming freshman, who is Black, said picking Howard in Washington, D.C., was about something bigger than basketball — it was about inspiring other high school players to attend a "historically Black college or university," or HBCU, in a bid to help enhance their prominence on the court and in the classroom.

"I'm trying to bring awareness to the contributions Blacks have made to society," Maker said. "When I went on my Howard visit, it was great, so five-star recruits should consider HBCUs seriously like what I've done."

If it had been the early 1950s, Maker's decision wouldn't have raised eyebrows. In those days, most Black college athletes attended HBCUs, and each year dozens would make their way to the NBA or NFL. But after U.S. colleges integrated in 1954, young Black sports stars found themselves heavily recruited to play at colleges with predominantly White student populations.

In the ensuing decades, college basketball became a way for such schools to burnish their reputations, as well as build lucrative athletic programs. For example, the University of Kentucky's basketball team generated an average of $56 million per year in revenue between 2016 and 2019, while Duke University's program brought in around $35 million annually over the same period, according to Forbes.

By contrast, basketball programs at HBCUs rarely top $1 million in annual revenue, according to data from the U.S. Department of Education. Some of the nation's nearly 100 historically black schools have also seen their enrollment decline, a financial challenge compounded by federal funding for HBCUs falling 42% between 2003 and 2015.

As some HBCUs struggled and predominantly White schools consolidated their advantage in college sports, basketball powerhouses such as the University of Kansas, Syracuse University and University of Connecticut came to be seen as stepping stones to the NBA. That perception has made it almost impossible to recruit top Black athletes.

To be clear, most of today's top NBA stars hail from only a dozen or so colleges — all of which are predominantly White schools. Still, HBCU coaches refute the claim that attending a basketball giant is essential for a professional career, pointing to the Philadelphia 76ers Kyle O'Quinn, from Norfolk State, and Houston Rocket Robert Covington, of Tennessee State.

"The amount of resources that have been taken away from HBCUs and put into the infrastructure of predominantly White institutions make some believe these [schools] are better prepared to make Black students become professional players and viably employed people," said Kenneth Blakeney, Maker's coach at Howard.

A move by more elite high school athletes to attend HBCUs could change that thinking, according to experts. Jonathan Swindell, CEO of HBCU Hub, a service that connects high school athletes with coaches at historically black schools, said signing a coveted athlete creates buzz and raises a school's profile. That often leads to increased enrollment.

HBCUs attracting more top high school athletes also means "more people would go to the games, which means more revenue for the university," said Nicholas Schlereth, who teaches sport management at Coastal Carolina University.

That would also give historically Black schools leverage in negotiating more lucrative broadcasting contracts. ESPN, which has the biggest contract to show college hoops, rarely televises HBCU games, Schlereth noted. Appearing in two or three nationally televised college basketball games can ultimately generate $1 million for a college per season, he said.

But those larger contracts won't materialize unless more students follow Maker's path, said Patrick Rishe, a sports business professor at Washington University in St. Louis. "The major TV networks are not going to throw money at the HBCU conferences just because of a handful of players."

Other players make the leap

Although it remains to be seen how many sought-after players will eventually find their way to HBCUs, recent signs suggest the trend is real.

Trace Young of Hartford, Kentucky, drew interest from Kansas State University and the University of Southern California, but tweeted that he would only consider offers from HBCUs. He eventually chose Alabama State. Nate Tabor of Waterbury, Connecticut, also got offers from top basketball schools, but chose Norfolk State in Virginia.

"Nate is going to be a heck of a player for us," Robert Jones, Norfolk State's basketball coach, told CBS MoneyWatch. "We sold him on the dream of you can be anything you want to be at Norfolk State."

Mikey Williams, a 16-year-old in California who many consider to be the nation's best high school player, is also reportedly considering an HBCU — encouraged by NBA players including Carmelo Anthony and Demarcus Cousins. Cousins, who attended Kentucky but said he regrets not going to a HBCU, told Bleacher Report that he contacted Williams directly about his choice.

"I basically sent him a message saying 'You've got a chance to change sports as a whole," Cousins said. "Start a trend that already should have happened."

Jones of Norfolk States said students like Maker and Tabor have sparked interest in HBCUs among young athletes, but noted that parents and coaches also play a critical role. "We have to try to actually get some of these kids. We have to go get that top 50 or that top 100 kid."

Blakeney expressed excitement about what Maker brings to Howard's team. But he is even more enthused about what his star recruit's presence could mean for the future of all HBCUs.

"A student-athlete will look at this and say 'Oh, I don't have to go to a Power-5 school," Blakeney said. "It will open up the conversation even more, and they'll see a HBCU education as a viable opportunity."

For his part, Maker said there's nothing wrong with attending a college known for its athletic programs. But he encouraged Black players to at least explore attending a historically black school.

"It's important for me to be a pioneer," he said. "I want to inspire the youth to take this route seriously. It's a different route, but at least take a visit."