Heroin in the Heartland

The following script is from "Heroin in the Heartland" which aired on November 1, 2015. Bill Whitaker is the correspondent. Tom Anderson and Michelle St. John, producers.

Federal and local authorities all over the country say it's the biggest drug epidemic today. Not methamphetamines or cocaine, but heroin.

You might think of heroin as primarily an inner-city problem. But dealers, connected to Mexican drug cartels, are making huge profits by expanding to new, lucrative markets: suburbs all across the country. It's basic economics. The dealers are going where the money is and they're cultivating a new set of consumers: high school students, college athletes, teachers and professionals.

Heroin is showing up everywhere -- in places like Columbus, Ohio . The area has long been viewed as so typically Middle American that, for years, many companies have gone there to test new products. We went to the Columbus suburbs to see how heroin is taking hold in the heartland.

Bill Whitaker: I'm sitting here looking at you, and you look young and fresh, you're the girl next door. And you were addicted to heroin.

Hannah Morris: I mean, obviously it's very flattering that you say, like, I don't look like a junkie. But even Miss America could be a junkie. I mean, anybody can be a junkie.

Hannah Morris is in college now. She says she's been clean for a year, but in high school she was using heroin. Hannah lives outside Columbus, in the upper middle class suburb of Worthington. Her parents are professionals. The median income here is $87,000 dollars a year. Before she got hooked on heroin, Hannah thought it was just another party drug.

Bill Whitaker: How did you get to those depths? What was the path you took?

Hannah Morris: It started with weed and it was fun, and I got to good weed . Went to-- oh my gosh, I went to pills, and it was still fun. You know, Percocet, Xanax, Vicodin, all that kinda stuff. And then yeah, heroin. I started smoking it at first.

Bill Whitaker: So you were what, 15?

Hannah Morris: Yeah. And I was like, oh my gosh that was amazing.

Bill Whitaker: You remember it even now?

Hannah Morris: Oh yeah. Let's say I've never done a drug in my life. I would normally be happiness at a six or a seven, at a scale out of 10, you know. And then you take heroin and you're automatically at a 26. And you're like, I want that again.

Hannah says the heroin was so addictive that rather quickly she and several other students went from smoking it at parties to shooting it up at high school.

Hannah Morris: Like, doing it at school in the bathroom.

Bill Whitaker: A syringe?

Hannah Morris: A syringe. I would have it in my purse, all ready to go.

Jenna Morrison has struggled to remain clean for almost three years. She comes from a town that is smaller and more rural than Hannah's. Jenna says her addiction started with legal opiates -- pain pills you can get with a prescription. Chemically, they're almost identical to heroin.

Jenna Morrison: I got on pain pills pretty bad when I was probably between 15 and 16.

Bill Whitaker: And the heroin came...

Jenna Morrison: When I was 18.

Bill Whitaker: Was it an easy transition from the pain pills to heroin?

Jenna Morrison: Very, because I didn't realize at the time that heroin is an opiate. I didn't know that that was the same thing as the pills that I was using.

Bill Whitaker: Why were you using all these drugs?

Jenna Morrison: I'm in a small town. There was nothing to do. And I was hanging out with older people. So, that was our way of having fun, partying.

"It's in every single county. It's in our cities but it's also in our wealthier suburbs. It's in our small towns. There is no place in Ohio where you can hide from it."

Mike DeWine: This is the worst drug epidemic I've seen in my lifetime.

Mike DeWine is the attorney general of Ohio. He's a former U.S. senator, congressman, and a county prosecutor. We met him at a state crime lab outside Columbus.

Mike DeWine: It's in every single county. It's in our cities but it's also in our wealthier suburbs. It's in our small towns. There is no place in Ohio where you can hide from it.

Bill Whitaker: It's that pervasive?

Mike DeWine: There is no place in Ohio where you couldn't have it delivered to you in 15, 20 minutes.

Hannah Morris: I can text and say, "Hey do you have this?" We can meet. The-- they would bring it to my house, leave it under the mat. It's pretty easy to get.

Bill Whitaker: Full service.

Hannah Morris: Uh-huh, yeah. To me it was easier to get than weed or cocaine, definitely easier.

Dealers with connections to the Mexican cartels, sell heroin everywhere...even in this department store parking lot outside Columbus. Our cameras captured the purchase of this heroin by an undercover police informant. Attorney General Mike DeWine's staffers say the Mexican heroin can be cheap - $10 a hit, or less. Some of it is cut with other drugs that make it even more powerful and deadly. And dealers keep inventing new ways to outwit law enforcement.

Bill Whitaker: And what do you have here?

Jessica Kaiser: These are actually tablets. So-- they are pressed to look like an actual prescription tablet, but they contain heroin.

Bill Whitaker: Heroin in pill form.

Jessica Kaiser: That look like pills, correct--

Bill Whitaker: This is new.

Jessica Kaiser: Very new, we've only seen a few cases in the lab.

And something else Mike DeWine says is new since his days as a county prosecutor: Heroin has lost its stigma as a poisonous, back-alley drug.

Mike DeWine: There's no psychological barrier anymore that stops a young person or an older person from taking heroin.

Bill Whitaker: So who is the typical heroin user in Ohio today?

Mike DeWine: Anybody watching today, this show-- it could be your family. There's no typical person. It just has permeated every segment of society in Ohio.

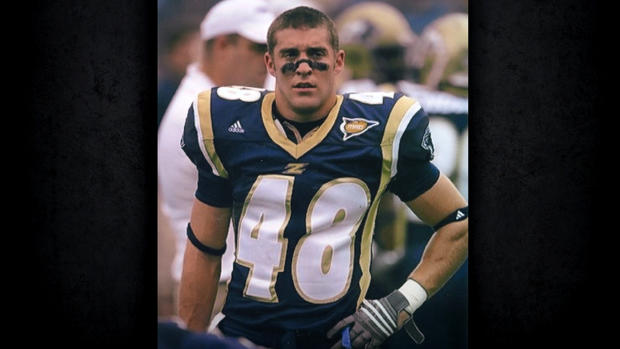

Even the well-to-do town of Pickerington, 30 minutes outside of Columbus. Tyler Campbell was a star of the high school football team. He went on to play Division I at the University of Akron. For Tyler, heroin wasn't a party drug. His parents, Wayne and Christy Campbell, say his heroin habit grew from his addiction to opiate painkillers, prescribed legally after he injured his shoulder.

Bill Whitaker: What were the pills?

Christy Campbell: It was--

Wayne Campbell: Vicodin.

Christy Campbell: Vicodin. Yeah--

Wayne Campbell: He had 60 Vicodin for his shoulder surgery.

Bill Whitaker: That's a normal prescription?

Wayne Campbell: For that procedure.

It's easy for kids to sell their excess pills. They're popular recreational drugs in high schools and colleges -- so MUCH in demand that one pill can cost up to 80 dollars.

Pill addicts like Tyler often switch to heroin because it's a cheaper opiate, with a bigger high. Tyler was in and out of rehab four times. The night he came home the last time, he couldn't fight the uncontrollable urge that is heroin addiction.

He shot up in his bedroom and died of a heroin overdose. He wasn't the only addict on his college football team.

Wayne Campbell: Unfortunately, the quarterback died four months after Tyler, in 2011--

Christy Campbell: Same. Of--

Wayne Campbell: --same situation.

Christy Campbell:--accidental overdose.

After Tyler died, the Campbells met many families whose children were heroin addicts in the suburbs of Columbus. Like Tyler, most got hooked on pills first.

Bill Whitaker: Started with pain pills?

Parents: Absolutely.

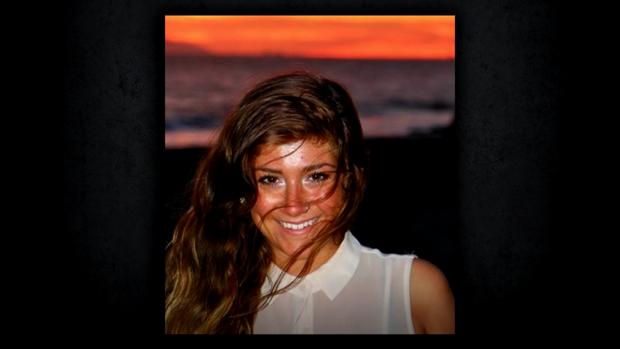

T.J. and Heidi Riggs' daughter died of a heroin overdose. Marin was a high school basketball player and captain of her golf team. Lea Heidman and Brian Malone's daughter Alyssa died of an overdose earlier this year. Brenda Stewart has two sons in recovery. Tracy Morrison is Jenna Morrison's mother and has a second daughter who is also a recovering addict. Rob Brandt's son was an addict.

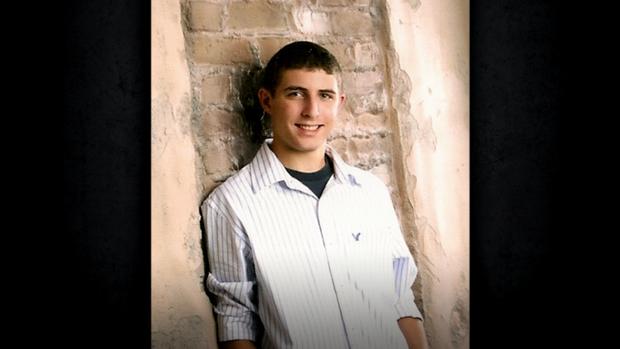

He says his son Robby got hooked on pain pills prescribed by a dentist after his wisdom teeth were removed. He was in training with the National Guard, hoping to serve in Afghanistan.

Rob Brandt: And when he came home, he met up with an old friend that he used to buy and sell prescription medications with and that old friend introduced him to heroin. And we did the-- we did rehab, we did relapse, we did rehab and he got clean. But the drug called his name again and-- and he said yes and that was the last time and he passed from an accidental overdose.

For many of these parents... the hardest thing to accept was losing their children after they thought they'd finally beaten the addiction.

Lea Heidman: She passed away the day after Saint Patrick's Day and she posted on Saint Patrick's Day a picture of her on her laptop, studying, doing homework, saying, "No partying for me, not even a single drink, I'm staying in and I'm-- and I'm working." And the next day she used and that was the last time she used.

Tracy Morrison: I am a nurse...

Tracy Morrison, Jenna's mother, trained to be a nurse more than 30 years ago. She says the medical profession must bear some responsibility for the heroin epidemic. She says doctors overprescribe pain medications.

Tracy Morrison: I graduated in the 80s. I was a nursing director when we decided to swing the pendulum from not treating pain to treat everybody's pain. I was a part of that. And at that time, I had no idea that we were addicting people.

Last year, three quarters of a billion pain pills were prescribed by doctors in Ohio - nearly 65 pills for every man, woman and child in the state.

Bill Whitaker: How did you respond when your daughters told you they were using heroin?

Tracy Morrison: Well, they first told me they were using the pills and how I found out they were using heroin was I came home from work one day, made dinner and I was yelling for my youngest daughter to come for dinner and she didn't and I walked into her bedroom and her boyfriend was shooting her up.

Bill Whitaker: You saw this?

Tracy Morrison: I saw it.

Bill Whitaker: What did you do?

Tracy Morrison: Dropped the plate of food. I dropped it. And I was hysterical.

Tracy's daughter Jenna is 25 now. She knows she's lucky to be alive.

Jenna Morrison: In my addiction I have been to rehab 17 times and I had been to jail six or seven times. So every time I went to jail I got out, went to rehab, came home and relapsed, and then did it all over again.

Bill Whitaker: You overdosed as well?

Jenna Morrison: Uh-huh (affirm).

Bill Whitaker: How many times?

Jenna Morrison: I only overdosed once, and I woke up in an ambulance.

"In my addiction I have been to rehab 17 times and I had been to jail six or seven times. So every time I went to jail I got out, went to rehab, came home and relapsed, and then did it all over again."

Jenna would have died if Emergency Medical Technicians hadn't injected her with Naloxone Hydrochloride, also called Narcan. It quickly reverses the effects of opiates in the brain.

The heroin problem in Ohio is so big, families and friends of addicts -- not just health professionals -- are being taught to administer Narcan, which is now available without a prescription.

(Nurse: This is what it looks like, this is the little purple cap, actually is the medication.)

Though she's a nurse, Tracy Morrison says at first she had no idea her daughters were addicts. Neither did the other parents. But they feel they missed all the signs and let their children down.

Bill Whitaker: You feel guilty?

Male voice: Every day.

Heidi Riggs: You lost the battle, so you're always gonna say, "Is there something I could have done differently?" Is-- you know, did-- why didn't I notice it when I had missing spoons that it wasn't because, you know, they left cereal bowls upstairs, it was actually because, you know, she was using them to shoot heroin. But who would have thought our children would ever do heroin?

All of these parents say they wanted to talk to us because too many other families are embarrassed, in denial about their kids' heroin use. These parents say the stigma and shame are compounding the epidemic.

Heidi Riggs: No one was talking about that we had heroin in Pickerington. And so, for us, we were total shock when it happened. And-- but the struggle was the stigma.

Brenda Stewart: Never say, "Not my child."

Male voice: Yeah, right.

Brenda Stewart: Because you never know. It could end up being your child.

Brian Malone: You never wanna get that call. You never wanna get that call.

Bill Whitaker: The call you got?

Brian Malone: The call you got, and we got the call.

Today, heroin overdoses take the lives of at least 23 people in Ohio every week. We were told many other heroin deaths go unreported.

Bill Whitaker: I'm sure there are some who would be watching this and would say, "Heroin addicts are junkies and they brought this on themselves, so why should we care?"

Tracy Morrison: Because we don't throw diabetics who sit on the couch eating Bon Bons and smoke and they weigh 300 pounds in prison. We don't belittle them and there's not a big stigma; we don't do that to people that chain smoke and develop lung cancer. It's a chronic relapsing brain disease, period, amen, end of story and we need to accept it-- even if it makes people uncomfortable. And if people don't like that, I'm sorry.